Anger grows as Denver mayor extends Flock camera contract

Inside a modest equipment rental building in north Denver, close to 700 people gathered for a community town hall on Wednesday evening to call for Mayor Mike Johnston to turn off the city’s 111 Flock Safety license plate-reading cameras.

Just hours before the meeting, Johnston announced that the city would extend its contract with the Atlanta-based technology company against the wishes of the City Council and despite public outcry over privacy concerns.

Angry and suspicious of the mayor’s new “no cost” deal with Flock, residents who poured into a large conference room inside the Geotech Environmental building spilled into overflow rooms, calling for answers and for the Johnston administration to explain its unilateral decision.

Agencies must now negotiate an agreement with Denver for access to LPR data, with the understanding that any data sharing with the federal government regarding civil immigration enforcement will result in an immediate loss of access and referral to the Colorado Attorney General’s Office for prosecution.

Should Flock be found responsible for unauthorized sharing, the company would be liable for a $100,000 fine per instance.

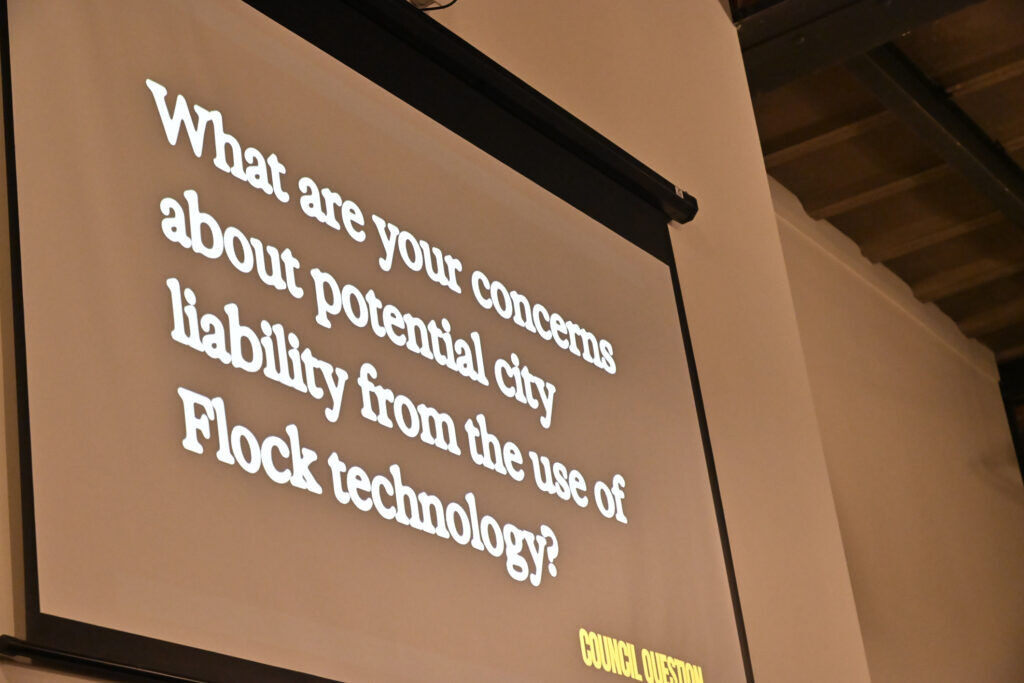

Organized by multiple privacy and civil rights groups, as well as several neighborhood organizations, attendees peppered city officials, including Johnston’s own policy director, Tim Hoffman, with questions about data leaks, privacy and the city’s “backdoor” dealings with Flock.

Critics argue that Johnston has not only demonstrated executive overreach with the new contract, but also an “unwillingness to be accountable to the public.”

At-large Councilmember Sarah Parady, who has been critical of Johnston’s dealings with Flock, said she was “stunned” to learn of the new contract, stating that the mayor “has been negotiating secretly with the discredited CEO of Flock Safety and signing another unilateral extension of this mass surveillance contract with no public process and no vote from the City Council or input from his own task force.”

Johnston told Denver Gazette news partner 9News that the purpose of that task force was to provide feedback and that, ultimately, he was in charge.

“A task force is designed to give feedback,” the mayor told 9News reporter Marc Sallinger, “A task force does not delegate executive power of the city to a member that sits on a task force – that was never the case, that was never communicated, that was never expected.”

“We have been taking feedback from both the community and council for several months and used that information to make the decisions you saw yesterday,” Johnston spokesperson Jon Ewing told The Denver Gazette. “That included shutting off access to everyone outside of DPD. This five-month extension is as much a trial period for Flock as it is for the city, and if we don’t feel we can move forward with them in March, we will consider another provider or alternatives.”

The mayor and Denver police have been longtime supporters of license plate-reading cameras, calling them a critical component of public safety.

Privacy advocates cite a series of missteps involving Flock camera users, in which unintended users — including federal agents — have had access to local data.

But while Denver’s new agreement with Flock cuts off access to agencies outside of Denver and prevents the city’s network from being accessed by federal agents, as well as law enforcement agencies outside of Denver, not everyone is confident that the mayor’s privacy guardrails are sufficient.

“It just makes me cringe,” Yasmin Flores, who attended the town hall, said. “It’s like every little piece that gets put into place connects to something bigger and more dangerous.”

Kathy Sandoval, a board member of the Villa Park Neighborhood Association, told the crowd she first found out about a new Flock camera being installed in her neighborhood through a city notification.

“We wouldn’t have known about it (the camera),” Sandoval said, “But this one had to be notified because it was in the encroachment. Otherwise, we would not have known about it.”

Sandoval said the city stated the purpose of the camera was for “general safety” and would be “monitoring license plates.”

The group has since filed a complaint with the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, but has yet to receive a response.

“When I ran for president of our neighborhood association, I was going to advocate for some sidewalks, clean up a few alleys, and afterward, I was going to have a few brewskies with my neighbors,” John McKinney, president of the East Colfax Neighborhood Association, said. “I never imagined that it involved trying to stand up for our Fourth Amendment rights as an American. We don’t deserve mass surveillance.”

Still, questions remain regarding the details of Johnston’s new agreement with Flock, particularly around whether or not the city’s acceptance of “free services” from a vendor hoping to garner a contract may violate ethics guidelines.

“We have reviewed this agreement and have no concerns on whether it meets charter standards,” Ewing said. “This is a trial run and an opportunity for us to prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that we can protect people’s privacy and also public safety. The eyes of many are on us. We welcome it because we know we have nothing to hide, that our values as a city that protects the vulnerable have not changed, and that this system has a proven track record of catching people responsible for the worst crimes, including the nine murder cases Flock’s technology has helped us solve and the serial rape suspect we’ve put behind bars.”

The new contract extends Flock’s services through March of next year.

Should the company’s performance during the five-month trial period be satisfactory, Johnston might then bring a long-term contract before the City Council for consideration.