No need to go ‘NIMBY’ on nuclear power | BIDLACK

There is a term well known in the political world, and that term is “NIMBY,” standing for “not in my back yard.” This term sums up the idea that people may support the concept of something, like, say, low-income housing, as long as it isn’t near them. And few things bring up NIMBY more than the issue of nuclear waste and where to put it.

One area in which I often differ with my fellow moderates is nuclear power. While there is lots of agreement on the importance of solar and wind power among my political group, nuclear power is often opposed, and I think that is a mistake. I won’t reargue the costs vs benefits of including nuclear power in our nation’s energy portfolio, as such arguments are only a brief internet search away, but I will argue that too many folks dismiss any role for nuclear and that that is a mistake. Nuclear energy offers a number of benefits, ranging from lower carbon emissions to a smaller land footprint, to reliable power 24 hours per day.

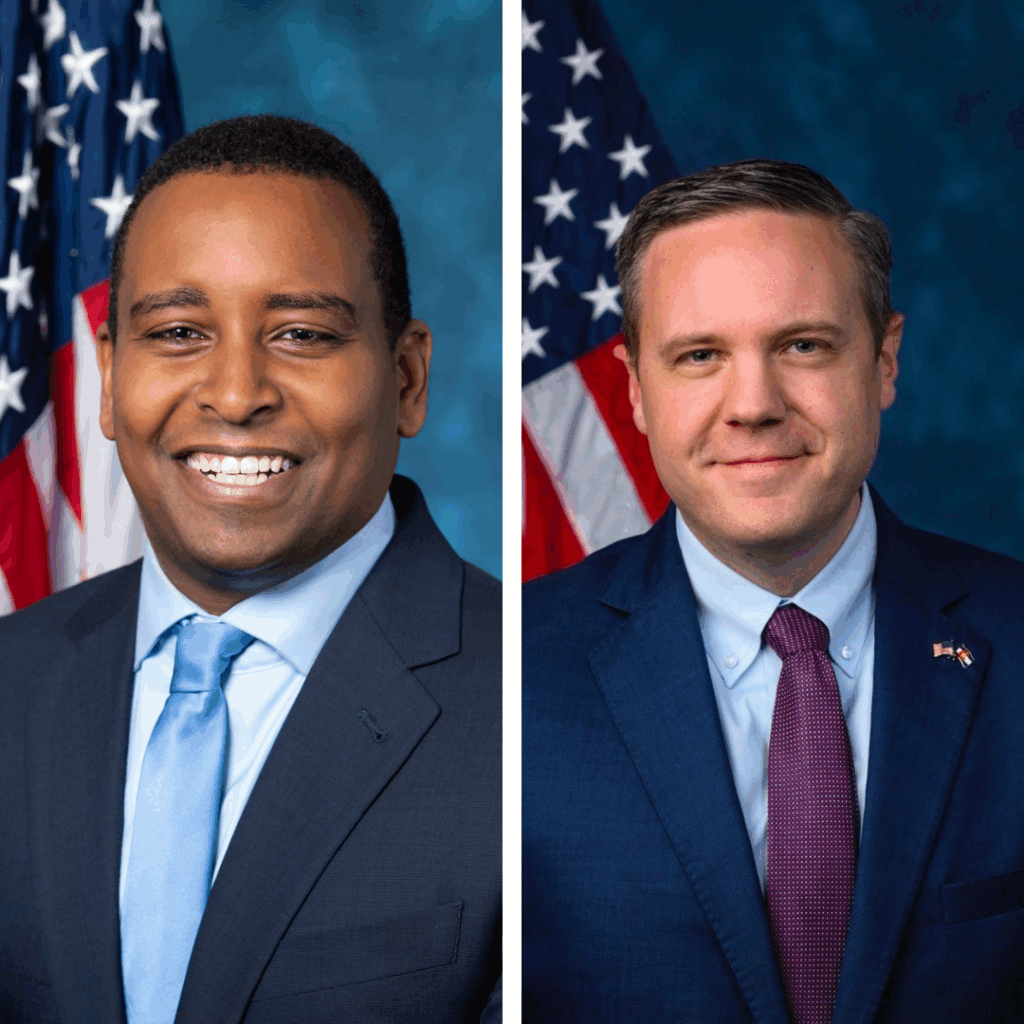

As with any energy source, there are, of course, negatives for nuclear, and one of the challenges, storage of nuclear waste, recently popped up in one of my favorite Colorado Politics segments, the Out West Roundup. The US Supreme Court recently ruled 6-3 to reverse a federal appeals court ruling that had canceled out a license issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to allow a private company in Texas to temporarily store some nuclear waste at a facility in southwest Texas, and the Court’s ruling likely also applies to another license for storage in New Mexico. I confess I’d like to have been in the Supreme Court’s conference room when they were hashing out this decision, as the author of the opinion was Justice Brett Kavanaugh, joined by Roberts, Sotomayor, Kagan, Barrett, and Jackson. There was a dissent from Justice Neil Gorsuch that Alito and Thomas joined. An odd mix, to be sure.

The storage of such waste has long been an issue. The US constructed a site in Nevada called the Yucca Mountain Storage Facility, as a permanent site for our nation’s nuclear waste, deep inside a mountain in remote Nevada.

And how much nuclear waste is currently stored there? Well, not much. How little? Zero.

Currently, after billions of dollars spent, there is no nuclear waste stored in Yucca Mountain, but rather it is found in temporary storage locations around the country. So, these temporary sites are quite significant, and might cause one to reflect on the word “temporary,” given that the “permanent” solution in Yucca Mountain appears to be off the table because, you know, NIMBY.

This is a complicated NIMBY though. There are two main issues opponents of Yucca Mountain storage often cite: the safety of transporting nuclear waste to the site, and the long-term stability of Yucca Mountain itself and the risk of accidents. Both strike me as challenges that can be dealt with though.

We already have testing information on so-called “nuclear fuel casks” that are somewhat like giant thermos bottles, albeit bottles that can take a direct impact from a speeding train without leaking. Most of the waste these days is moved on roads using such containers, and there are strict rules on how and when and where such shipments can take place. But in my view, the transportation issues are easily handled should we decide to open up Yucca Mountain.

The second risk is what people tend to fear the most, the idea of a nuclear accident. In my own doctoral studies, back in the 1990s, I devoted one entire chapter of my doctoral dissertation (amazingly still available on line) to the Chernobyl disaster, by far the world’s worst nuclear accident. I’ve been asked if “a Chernobyl” could happen here, and the answer is no, for lots of reasons. Interestingly, the only nuclear reactor in the US that used the now-rejected design that was used at Chernobyl was the Fort St. Vrain reactor just north of Denver. This small facility was intended to generate electricity for Denver and beyond, but it was plagued with issues, and it operated at no more that 15% over its 15 years of activity until it was shut down permanently.

But, of course, one example doesn’t really prove anything, so let’s talk about France. Today France has roughly 60 nuclear reactors and they provide a combined 68% of the nation’s electrical supply. And while there are ongoing issues regarding upkeep and maintenance, such issues also exist at oil refineries and other sources of fossil fuel production.

And so, the Supreme Court has ruled, albeit on apparently technical grounds, that states can license temporary nuclear waste storage, but the long-term solution continues to be, at least in this author’s eyes, Yucca Mountain.

Yes, there will be trucks and trains coming to Nevada from around the country, but we have proven safe means of transportation. And yes, the good people of Nevada will have to deal with some NIMBY issues, though the facility is 100 miles from Las Vegas and the largest population centers, so how far NIMBY reaches is a legitimate question. The facility itself is considered one of the most thoroughly and methodically studied geological formations on Earth. And the facility is already bought and paid for. There will, of course, be some start up costs once a brave leader makes the decision to use Yucca Mountain, but they will pale when compared to the costs of continued fossil fuel domination of our energy generation.

Starting Yucca Mountain up, and creating the needed infrastructure for transportation of nuclear waste thither, may well create some NIMBY feelings, but less so than likely already exist in the communities surrounding the roughly 100 temporary storage locations spread across 39 states.

So, with the Supreme Court’s ruling, Texas and New Mexico are set to add at least two more temporary sites to that list. I posit that our nation would be far better off by employing a smart nuclear energy policy that would include Yucca Mountain. I’m not holding my breath, but I would urge my fellow moderates to stop rejecting nuclear power options a priori.

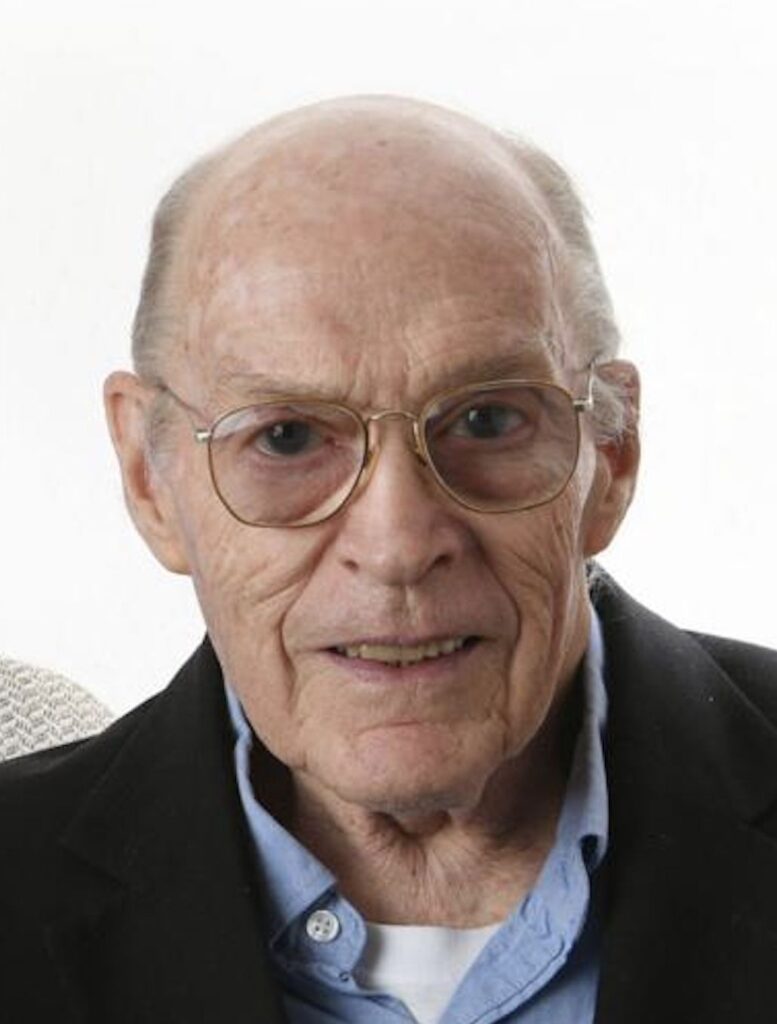

Hal Bidlack is a retired professor of political science and a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who taught more than 17 years at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs.

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: