Colorado Supreme Court rules government alone may pursue child neglect allegations

The government, and only the government, may pursue child neglect cases, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Monday, rejecting the argument that children or parents may continue litigating allegations of neglect after the government moves to dismiss.

In a 6-1 decision, the Supreme Court relied on the longstanding concept of “parens patriae,” which empowers the government to protect the welfare of those who cannot care for themselves. Consequently, while the government has the authority to intervene in the parent-child relationship, the court’s majority concluded nothing else authorizes a different party to take on that role.

“Indeed, to allow a child (or another non-state party, such as a family member or foster parent) to prosecute dependency and neglect actions risks transforming the government’s parens patriae authority to protect children into a weaponized family court system,” wrote Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez in the June 2 opinion.

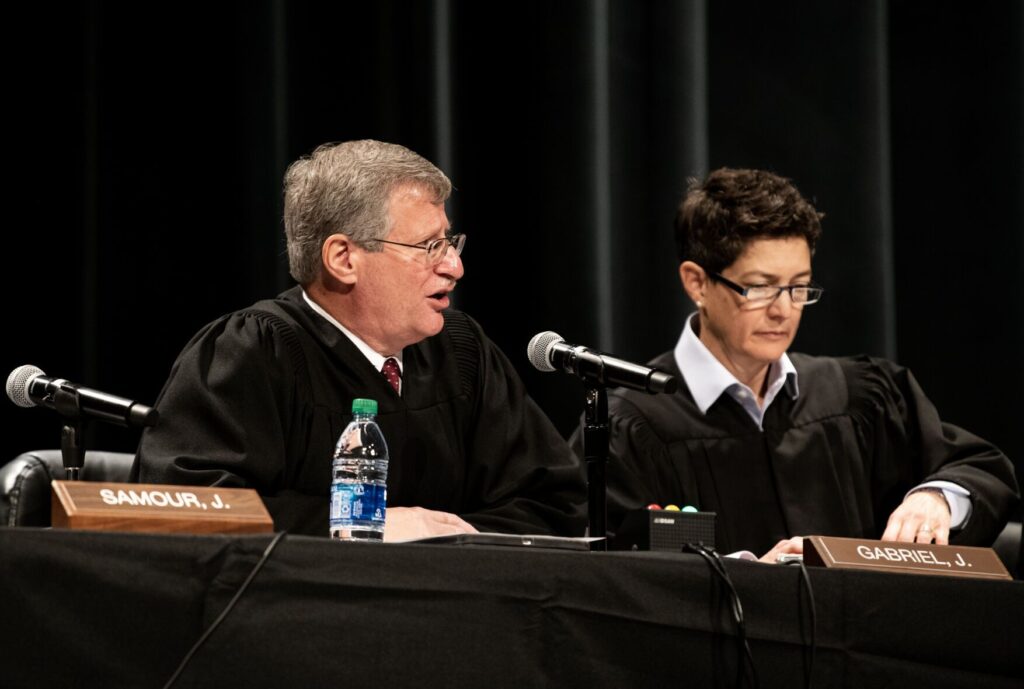

Justice Richard L. Gabriel dissented, arguing trial judges have significant oversight in child welfare cases, formally known as dependency and neglect proceedings. Therefore, he brushed off the concern of a “weaponized” legal process and instead accused the majority of “adopting its own policy preference.”

The majority “substantially undermines children’s and youth’s voices by giving unfettered authority to the (government) to dismiss a case, over the child’s or youth’s objection, for any or no reason,” he wrote.

In the underlying case, Denver Human Services filed a child neglect petition involving 13-year-old R.M.P. Allegedly, the teenager’s father repeatedly endangered R.M.P. through dangerous or abusive conduct. As a result, R.M.P. entered foster care and received an attorney for the child neglect case.

In February, the department moved to dismiss the case. It had investigated the allegations and determined R.M.P.’s accusations were false. Instead, R.M.P.’s own conduct was problematic, and the teenager had since been arrested. Denver believed R.M.P. should be returned to his father’s custody because there was a “real plan” for managing R.M.P.’s behavior going forward.

However, R.M.P.’s lawyer objected, arguing R.M.P. was, in fact, neglected. Rather than approve the government’s motion to dismiss, Juvenile Court Judge Laurie A. Clark opted to hold a hearing to determine if there was evidence supporting the original allegations of neglect. After hearing from R.M.P. and his father, Clark permitted the case to move forward for a determination of whether R.M.P. was neglected.

R.M.P.’s father turned directly to the Supreme Court, challenging Clark’s decision not to dismiss.

Multiple outside entities weighed in, including the Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel, which represents indigent parents in child welfare cases. The office warned that permitting child neglect cases to continue even when the government has withdrawn the allegations would substantially increase the cost of child welfare proceedings.

“If a child is permitted to prosecute a petition in dependency and neglect by virtue of their party status, no logical distinction exists to bar a parent” from pursuing a neglect case against the other parent, wrote attorney Melanie Jordan. Such a decision would “turn a narrowly tailored and limited governmental power designed to protect children into a weaponized family court system.”

Márquez, in the majority opinion, noted the government is the only entity authorized to file child neglect petitions. Although the proceedings are aimed at furthering the child’s best interest, the ultimate question is whether the government should “exercise its authority to intervene” in a family’s relationship.

“Allowing a child (or any non-state party) to override the State’s determination that a petition should be dismissed would be analogous to allowing the victim of a crime to prevent the district attorney from dismissing a criminal case,” she wrote. “Colorado law does not confer such a right.”

Gabriel disagreed with that analogy.

“Crime victims are not parties in a criminal case,” he wrote, whereas “children and youths like R.M.P. are parties in dependency and neglect proceedings. This is a distinction with a material difference, and in not recognizing that distinction, the majority eliminates substantial rights of these parties.”

Gabriel added that the question, to him, was whether the government may “unilaterally” dismiss a child welfare case without a judge providing oversight about the correctness of that decision. He believed the answer was no, and felt Clark acted appropriately by deciding if there was evidence supporting the initial allegations.

Chris Henderson, executive director of the Office of the Child’s Representative, which provides legal representation for children, also disagreed with the majority’s conclusion.

“The majority’s view contradicts recent law and legislative history, providing that children and youth are parties to their dependency and neglect proceedings and have the right to be heard on such matters of importance, presumably including the fundamental question of whether they are abused or neglected,” he said.

The case is People in the Interest of R.M.P.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated with additional comment.

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: