2 federal judges pitch lawyers on benefits of handing cases over to magistrate judges

Two of Colorado’s federal district judges, speaking on Tuesday about why lawyers should consent to having magistrate judges handle more cases, said they were disturbed that barely more than a dozen attorneys showed up.

“We’re concerned even about this turnout for two (district) judges speaking,” said U.S. District Court Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney at a discussion sponsored by the Faculty of Federal Advocates. “This is probably the lowest turnout in FFA history because nobody wants to talk about why they’re consenting or not consenting.”

Federal district courts employ multiple types of judges: Active district judges — also known as Article III judges after the constitutional provision establishing the judicial branch — are nominated by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. Senior district judges are semi-retired but still retain the ability to handle cases up to full time, if they wish.

Magistrate judges, also known as Article I judges, are hired by the district judges to assist with the workload of the trial courts. They serve eight-year terms and focus largely on preliminary and administrative matters in cases. In Colorado, they are randomly assigned cases individually and in tandem with district judges.

However, if the parties to a civil case all consent fairly early in the litigation, the magistrate judge assigned to the case can handle all aspects by themselves, including a jury trial.

U.S. District Court Chief Judge Philip A. Brimmer swears in U.S. Magistrate Judge Kathryn A. Starnella during her investiture on Oct. 13, 2023. Photo courtesy of Phil Weiser

Sweeney and U.S. District Court Judge S. Kato Crews, both recent appointees of Joe Biden, spoke at the Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse about why they recommend consenting to a magistrate judge. Among the top reasons: Article III district judges are required to handle felony criminal cases, and the legal deadlines for bringing the criminally accused to trial mean civil cases can get bumped on the docket.

“I’ve estimated spending at least 500 hours a year, if not 700 hours a year, on criminal matters,” said Sweeney. Under magistrate judge consent, “it’s giving them a lot more time and attention they can give to your case.”

The presentation by Sweeney and Crews occurred on the same day Judge Timothy M. Tymkovich of the Denver-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit spoke to a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee to advocate for the creation of 66 new district judgeships, including two for Colorado. Tymkovich’s prepared remarks informed Congress that magistrate judges make “substantial contributions” to the trial courts, but “their jurisdiction is limited.”

Crews, who is one of three former Colorado magistrate judges now serving as a district judge, said magistrate judges are involved in the governance of the court, have started programs to help litigants in various ways and assist with the selection of new magistrate judges. They also interact with litigants in person — particularly self-represented litigants — more often than the district judges.

“These were people that district judges have selected because they’re experienced. They’re experienced with federal court. They’re experienced in litigation,” Crews said. “The judges are familiar with these individuals and their quality and their skills as practitioners. These are highly experienced lawyers.”

U.S. Magistrate Judge S. Kato Crews testifies at his confirmation hearing to be a district court judge on March 22, 2023.

Sweeney and Crews said they were speaking up because the rate of consent has declined, with parties consenting to a magistrate judge only around 10% of the time. Crews also admitted they were unsure what caused the trend.

“We as a court can’t put our finger on it,” he said.

The judges passed out notecards for attendees to anonymously write down reasons why lawyers might not consent. The responses included “there’s so many new magistrate judges” and “there’s a perception an Article I is ‘less than’ an Article III.”

“That’s just simply not the case,” Sweeney said. She acknowledged there has been a wave of new magistrate judges appointed since 2021, but there have also been five new district judges. She added that the decline in consent rates predated the recent turnover.

One attendee commented that out-of-state law firms litigating opposite her reflexively respond, “Are you kidding?” when she raises the possibility of consenting to a magistrate judge. She said she encourages those lawyers to consult with attorneys who are familiar with Colorado’s court.

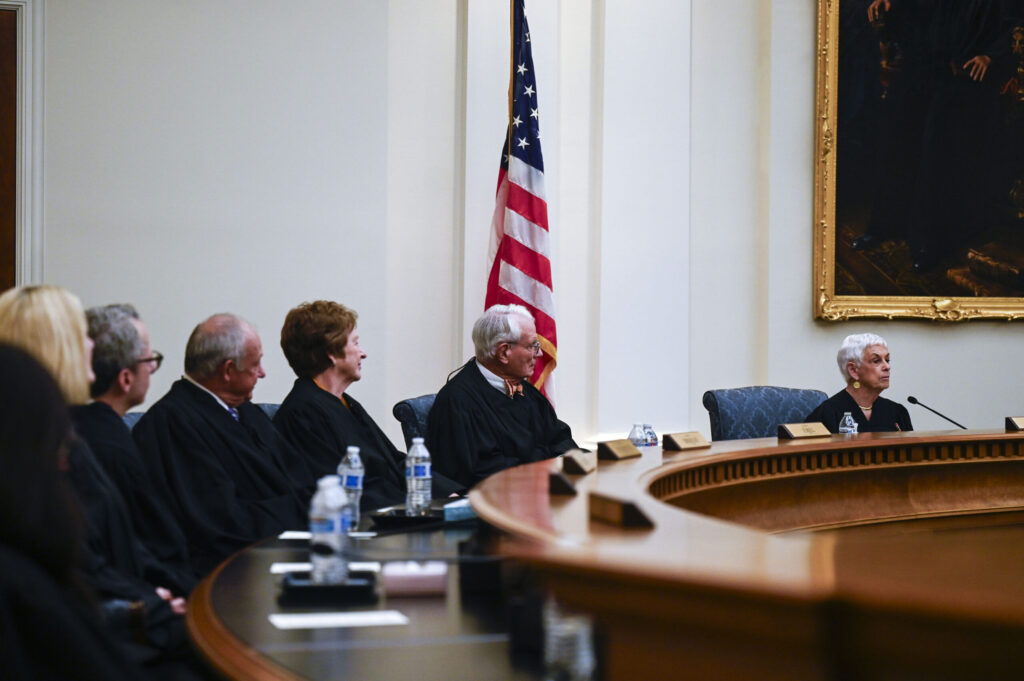

Attorney David Gartenberg applauds for U.S. District Court Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney at a legal event in Denver on July 21, 2023.

U.S. Magistrate Judge N. Reid Neureiter, who was in the audience, noted that many civil cases in the court are insurance disputes, car wrecks or slips-and-falls — which magistrate judges can easily handle quicker than a district judge.

“Not that we don’t love deep constitutional cases or really complex patent cases,” he said. But “it doesn’t make sense to waste these people’s time (the district judges) on that case.”

One of the court’s rules allows parties to consent to a magistrate judge’s handling of a single dispositive motion — for example, a motion to dismiss that can potentially end a case without a trial. Crews said that in all his years as a lawyer, a magistrate judge and a district judge, he had never seen anyone invoke that rule.

Sweeney noted the purpose of the rule is to dislodge motions that are pending on a district judge’s docket for an unreasonable period. But she also suggested lawyers think about invoking the rule for a different reason.

When a district judge and a magistrate judge are assigned to a case, district judges may ask magistrate judges to analyze a motion to dismiss or a motion for summary judgment and issue a recommendation. The parties then have the chance to object to specific portions of the recommendation, which the district judges then examine anew. Almost always, district judges uphold the entirety of a magistrate judge’s recommendation.

In 2023, Colorado’s federal district judges upheld magistrate judges’ recommendations entirely more than 88% of the time. Source: 2023 statistical report by Chief U.S. Magistrate Judge Michael E. Hegarty

“Why not consent to that being the final decision?” Sweeney wondered. “Absent some extraordinary circumstance, that’s gonna be the decision anyway. And all you’ve done is add time and expense for your client” by objecting.

One attendee said he disagreed with the “overall vibe” that consenting to a magistrate judge is desirable because it will move a case to trial faster. He suggested the approach was “a little pushy.”

“Nobody’s saying we wanna push you faster. I think the message is: This court understands delay is an access to justice issue,” responded Sweeney. “And if we have undue delay that cannot be justified, it is cutting off your client’s access to a timely resolution of their dispute. And that is a fundamental problem in the American legal system that I, for one, do not want to see continuing and perpetuating.”