Colorado civil rights commission has zero geographic diversity, audit says

Colorado’s civil rights commission has been hampered by vacancies, affecting its ability to do its job, a state audit found.

In addition, the audit raised questions about the commission’s neutrality, tied to legal responsibilities that the Division of Civil Rights said could impact its ability to remain neutral and keep its work confidential.

Notably, the audit, released on Monday by the Legislative Audit Committee, found so much confusion by both the legislature and the commission on its responsibilities that it’s unclear who’s supposed to be doing what.

The Division of Civil Rights — whose director is appointed by the Department of Regulatory Agencies, not the commission — conducts investigations and decides complaints involving discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations.

The commission does the rule-making, reviews appeals on cases dismissed by the Civil Rights Division, decides whether to hold hearings on cases for which there is probable cause, directs the division to investigate discrimination cases “and advises the Governor and the General Assembly on civil rights issues,” according to an October 2017 sunset review.

Currently, the commission has just five members, out of its required seven, and all five are from the Denver metro area, leaving rural and other urban areas outside of the region — such as Colorado Springs and Pueblo and Grand Junction — without representation. The commission hasn’t had a member who lived outside of the Front Range since January 2018.

And that fails to meet the statute’s requirement that commission members represent geographical diversity.

The audit found found that before a 2018 state law changed requirements for commission membership, 57% of commission members were located outside of the Denver metropolitan area.

“After 2018, the percentage of commissioners located outside of the Denver metropolitan area has decreased steadily,” and since 2021, the commission has lacked any members from somewhere other than the Denver metro area, the audit said.

“This is not consistent with the statutory requirement that commission members be as geographically representative as possible,” the audit stated.

Of the five members, one is a Democrat; the other four are unaffiliated. No Republicans have been appointed to the commission since Gov. Jared Polis took office in 2019.

The audit pointed to the 2018 law that changed who would sit on the commission. The legislature, which was then under split control, with Republicans in charge of the Senate and Democrats in charge of the House, squabbled for two years over that last rural member, Heidi Hess. The state Senate in 2017 rejected her reappointment to the board on a party-line vote, but she stayed on until January 2018, when she resigned.

Hess, of Clifton, was appointed to the board in 2013 as an at-large representative. She was then a Western Slope organizer for the LGBTQ+ organization One Colorado.

While a 2018 sunset review did not make any recommendations on changing the criteria for membership, a conference committee, working on the session’s final day, made major changes. The reasons behind those changes were never spelled out in the law, the audit noted.

The bill’s House sponsors, Rep. Leslie Herod, D-Denver, and then-House Speaker Crisanta Duran, D-Denver, didn’t explain those changes in asking for the adoption of a conference committee report.

Sen. Daniel Kagan, D-Englewood, said the changes were part of a hard-fought compromise, but the bill’s Senate sponsor, Sen. Bob Gardner, R-Colorado Springs, said he did not sign the conference committee report and voted against it. He also balked at the bill for its final vote.

“This is a conference committee report that does not do the one thing that this body did, 35-0, (on a prior Senate bill) to restore balance in the commission — to ensure gubernatorial appointments were subject to real legislative oversight,” Gardner had told the Senate at the time. “That does not exist in this bill.”

“We have not offered to you the kind of balance and oversight” the people should have, he said, adding that he asked the Senate to vote against the bill.

That’s when the criteria got more complicated.

Changes to the civil rights commission criteria, pre- and post-2018. Courtesy Colorado state audit report, 2024.

The audit found two reasons for the commission’s lack of representation, starting with the narrow criteria. It takes, on average, at least six months and as long as a year to fill a vacancy, substantially longer than it took prior to the passage of HB 12-1256. Before 2018, usually, the commission had another nominee ready to go before the term of a departing commissioner ended, the audit explained.

“Department staff said that the prescriptive nature of the statute means that they often have to find very specific qualities for a commission opening, such as finding someone who is a member of an employee organization, is not affiliated with a particular political party, and is part of a group that may be discriminated against,” the audit said.

The time commitment is another issue, the audit pointed out. The commission reviews 95 appeals per year, and it takes commissioners four to 10 hours to review those appeals prior to the commission one to two-day meetings, a volunteer commitment the audit called “lengthy.”

The division, in its response, agreed the law is overly prescriptive and suggested statutory change would improve the process, but it stopped short of saying it would ask the governor’s office for that recommendation.

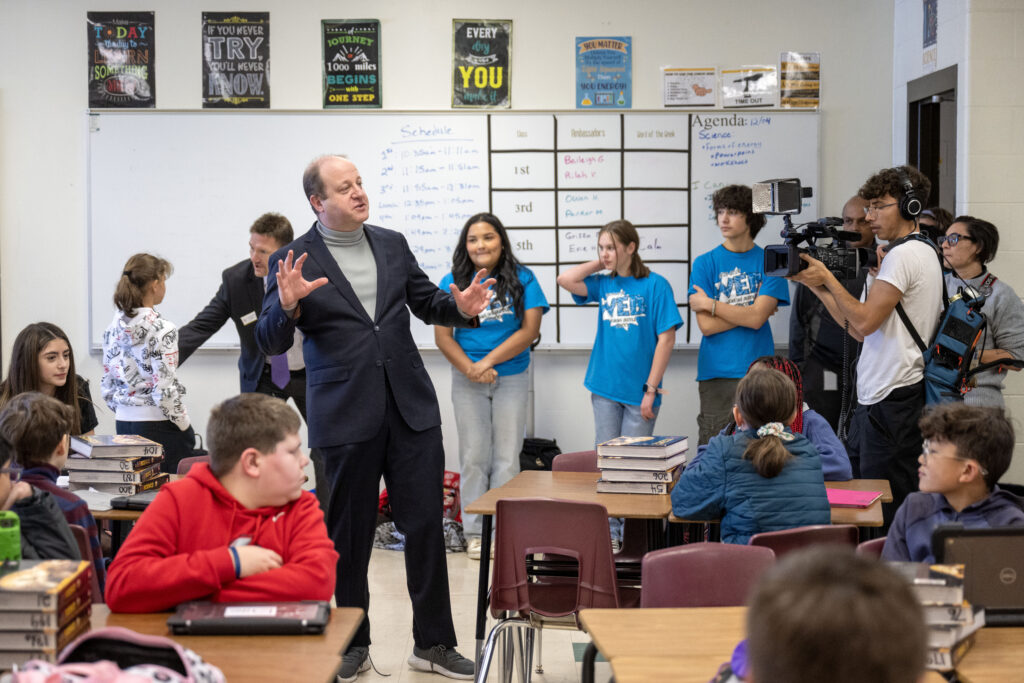

A spokesperson for Gov. Jared Polis told Colorado Politics that the governor “takes appointments to boards and commissions very seriously and always looks for the best, most qualified candidates for the job while also meeting requirements outlined in statute.”

“As the audit says, the statute is very prescriptive since the changes in 2018, which has made recruiting and retention difficult, and the governor strongly supports making the positions more flexible to help with greater geographic diversity. This has resulted in two current openings for the seven-member board,” the governor’s office said. “The governor previously appointed Ajay Menon, who was from Fort Collins. He looks forward to filling the two current vacancies and encourages qualified Coloradans from across the state to apply.”

“It’s par for the course with this governor,” said Sen. Byron Pelton, R-Sterling, who sat in on the audit committee to replace another member. “It’s sad we don’t have rural Colorado represented.”

“We see civil rights discrepancies as well, why wouldn’t it be important on that commission?” he said.

But then, he added sarcastically, that “Denver always knows what’s best for all of rural Colorado.”

Rep. Lisa Frizell, R-Parker, who chairs the audit committee, said there didn’t appear to be any interest from the committee in going after a bill on statutory change.

“It’s unfortunate,” she said, “but an initiative like that should come from the majority party.”

The growth in vacancies is in part tied to the second problem — the division managing responsibilities that are statutorily tasked to the commission.

“The roles of the Division and Commission have changed over time and the Division sees some Commissioner powers and duties at odds with other Commissioner statutory responsibilities. However, the Division and Commission have not evaluated the powers and duties of the Commission listed in statute to determine if they are still appropriate,” the audit found.

The audit said that raises three issues: neutrality, confidentiality and transparency, and capacity.

Masterpiece Cakeshop questioned commissioners’ neutrality

Commissioners are required to be neutral and cannot take on an advocacy role, the audit said, pointing out the body’s neutrality was called into question during the first Masterpiece Cakeshop lawsuit that the U.S. Supreme Court heard in 2017.

“The Supreme Court opinion called some statements made by Commissioners during a public meeting ‘clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs’ of the business owner,” the audit said.

In Masterpiece Cakeshop, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that Colorado was hostile toward Lakewood baker Jack Phillips’s religious beliefs after he refused to create a wedding cake for a same-sex couple, and that the state’s civil rights commission, thus, violated Phillips’s First Amendment rights.

In the audit, the division said the commission could compromise its confidentiality and neutrality if it conducted studies or make policy recommendations based on cases it reviews.

The division also said the commission could violate the state’s open meetings laws if multiple commissioners participated in outreach events, which would require the division to record and take minutes of those meetings. Finally, the division said volunteer commissioners likely do not have the time or legal knowledge to make policy recommendations and conduct discrimination studies.

Since 2009, the division, not the commission, has handled those responsibilities, although those tasks legally remain under commission authority.

The audit pointed out that the legislature, as well as commissioners themselves, appears to be confused about what responsibilities are handled by the division and what’s under the purview of the commission.

The audit recommended the Department of Regulatory Agencies, which houses the division, and the Colorado Civil Rights Commission “should evaluate the statutory powers and duties of the Division of Civil Rights and Commission to determine whether these powers and duties are still appropriate, and if they should work with the General Assembly to amend statute to reflect the current operations of the Division and Commission.”

On that, the Division and DORA not only agreed to evaluate the statutory roles of both entities but stated that, “if appropriate” it would seek statutory changes.