Appeals court: Defendant’s traumatic brain injury not a basis for finding life sentence unconstitutional

Despite the state legislature’s recognition that traumatic brain injuries lead to a greater risk of involvement with the criminal justice system, Colorado’s second-highest court on Thursday ruled such injuries do not make a defendant’s life sentence cruel and unusual.

Stanley Paul Jurgevich, who is serving life in prison with the possibility of parole for his 1988 killing of George Salisbury III, argued his sentence was “grossly disproportionate” considering he suffered a traumatic brain injury when he was 11 years old that permanently affected his behavior.

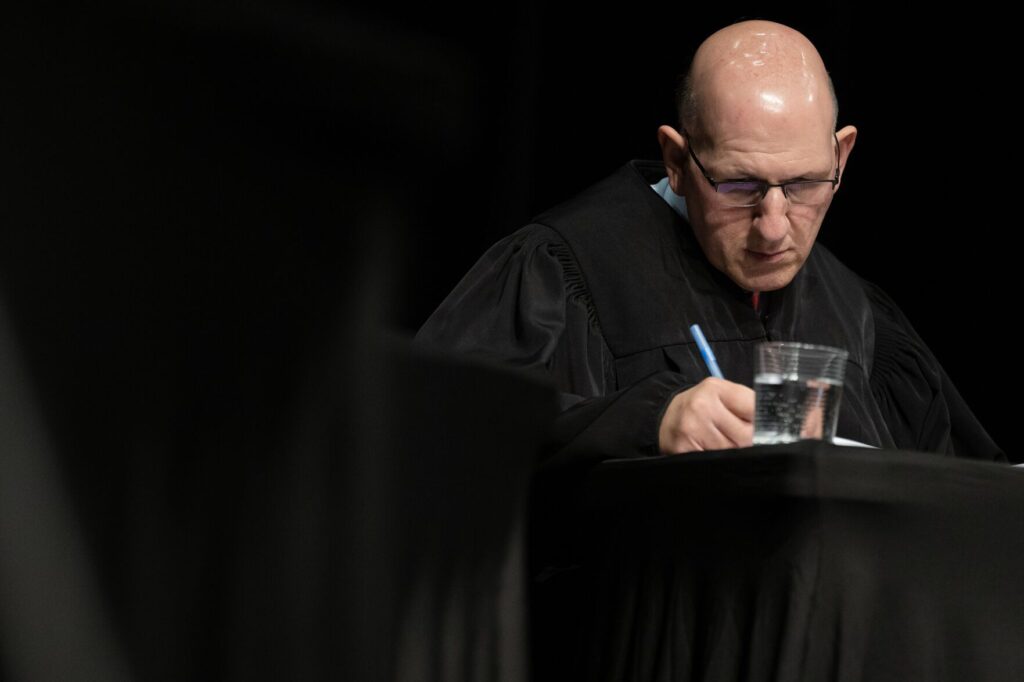

“As Jurgevich correctly notes, the United States Supreme Court has determined that certain punishments are disproportionate for certain classes of offenders,” wrote Judge Timothy J. Schutz for a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals. “For example, the Supreme Court has held that the death penalty is categorically barred for defendants who are insane, defendants with an exceptionally low I.Q., and juveniles.”

But the panel found nothing to suggest a traumatic brain injury rendered Jurgevich’s life sentence unconstitutional for a crime he committed as an adult.

Jurgevich previously challenged his conviction unsuccessfully. In late 2021, he filed a new petition in Routt County District Court arguing his sentence was grossly disproportionate and violated the constitutional prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

Earlier that year, the legislature created a pilot program to provide support and evaluation for a limited number of prisoners with brain injuries.

“Traumatic brain injury can affect a person’s ability for self-regulation, planning, organization, judgment, reasoning, and problem solving,” the bill noted. “In fact, the consequences of traumatic brain injury are often ‘linked to violence, infractions in prison, poorer treatment gains, and reconviction’ as well as ‘ongoing mental health and drug and alcohol problems’.”

The legislation also cited research from Kim Gorgens, a University of Denver professor, that found 54% of adults in Colorado’s jails and problem-solving courts, on average, had traumatic brain injuries. Other studies have suggested the prevalence of brain injuries is three to 10 times higher among incarcerated persons than in the general population.

“There is certainly an evolving and growing understanding of the importance of traumatic brain injuries and the need for evaluation and treatment,” acknowledged Chief Judge Michael A. O’Hara III in denying Jurgevich’s petition. “Mr. Jurgevich, however, has not pointed to a Colorado or a federal case or statute recognizing persons with TBIs as a class of defendants who, based on their status or characteristics, would require categorical rules on the scope of punishment the state can impose.”

Turning to the Court of Appeals, Jurgevich argued there had been “significant advancements” in neuroscience since his trial more than three decades ago. Just as the Supreme Court has found that children are less culpable than adult defendants by nature of their brain development, Jurgevich urged the appellate panel to find the same to be true of defendants with traumatic brain injuries.

“Both categories are defined by individuals who, through no fault of their own, exist with diminished cognitive function in areas that include reasoning, decision-making, problem solving, and psychosocial behavior,” wrote public defender Lisa Weisz.

The Court of Appeals observed that since Jurgevich’s trial, the legislature had changed the law to be harsher for those convicted of first-degree murder, which now carries a life sentence without the possibility of parole. Lawmakers have not addressed sentences specific to those with traumatic brain injuries, notwithstanding their creation of a pilot program in 2021.

“We agree with Jurgevich that this legislation reflects a growing sensitivity to the burdens — and the possible decrease in moral accountability — created by TBIs,” Schutz wrote in the April 11 opinion. “But the legislation does not reflect an intention to categorically prohibit the sentence imposed on Jurgevich. If the General Assembly intended such a result, it could certainly have said so.”

Jurgevich will be eligible for parole in 2028, when he will be 80 years old.

The case is People v. Jurgevich.