Colorado justices tentatively agree that judges’ appearance of bias can matter in criminal appeals

Although members of the Colorado Supreme Court on Tuesday seemed unconvinced that an El Paso County judge should have recused herself from a case because she was previously the victim of a similar crime, the court was less receptive to the government’s position that a judge’s appearance of bias can almost never be grounds for reversing a conviction.

Jurors found Khalil Jamandre Sanders guilty in 2017 of assault, menacing and the illegal discharge of a firearm after he shot at and injured the driver of another car in an apparent act of road rage. He is serving 32 years in prison.

On appeal, Sanders challenged the convictions based on a disclosure his trial judge made after the trial was underway that she had been randomly shot at while driving a few years prior. The defense moved for her recusal on the grounds that she could not be neutral, but she declined to step aside, reasoning her experience was too dissimilar from Sanders’ case.

“I find myself wondering whether a reasonable person looking at this would really find that an incident that occurred some three years earlier, that did not involve a road rage incident, and that didn’t result in injury would somehow keep this judge from being impartial,” said Justice William W. Hood III during oral arguments. “Help me understand how they really are so similar that there’s this legitimate concern.”

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office, meanwhile, argued that except in “extreme” cases involving a strong risk that a judge is biased, the appearance of a judge’s partiality on its own can never be grounds for reversing a conviction. Members of the Supreme Court appeared to reject that hardline approach to bias.

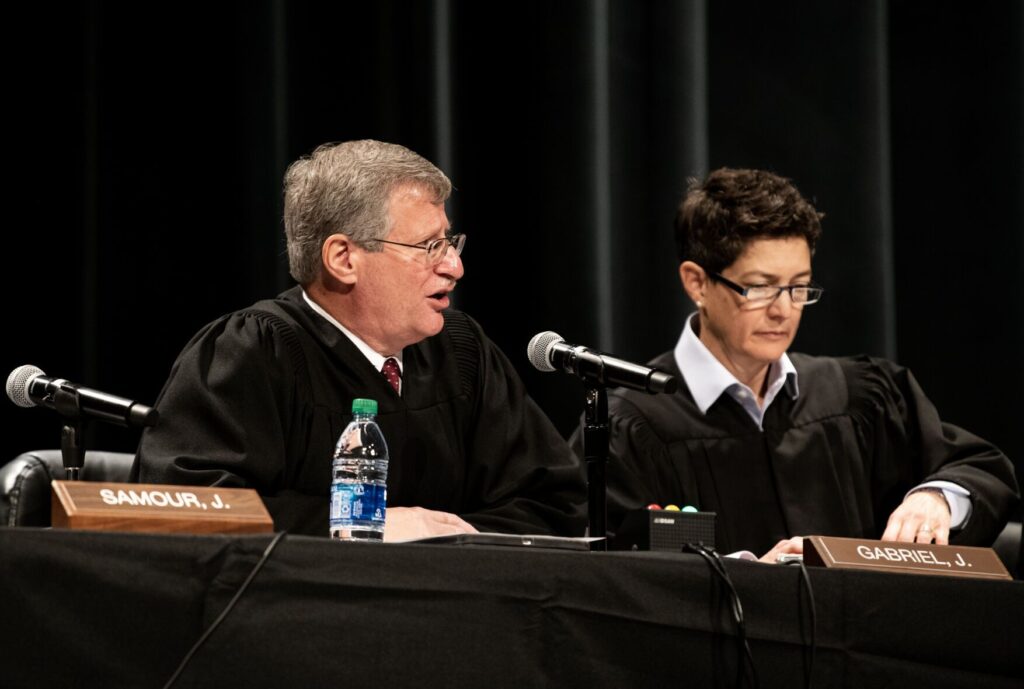

“I worry when you go back to ‘appearances just do not matter.’ Well, they might,” said Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr.

During jury selection in Sanders’ trial, in which multiple jurors spoke of their own experiences with road rage, then-District Court Judge Barbara L. Hughes told the parties she “would be remiss” if she did not disclose something: A few years prior, she was driving in Colorado Springs and saw people fighting in the street. She honked at them and someone shot at her car.

“I heard pop, pop, pop, ping, and it hit the spoiler of my car. I had to duck,” Hughes recalled. “There was a case report, I guess, a police report, but there was never any filing of any charges. There was never any person that was identified as the shooter.”

Sanders’ attorney requested that Hughes recuse herself because she could not “be unprejudiced with respect to the facts of this case based on her own personal experiences.” Hughes declined, asserting she had “no interest in the outcome, no interest in either party,” and her experience was not similar to Sanders’ case.

On appeal, Sanders argued Hughes needed to recuse under the constitutional guarantee of due process, under state law, under the rules of criminal procedure and, finally, under the rules of judicial conduct. A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals disagreed with him.

“Sanders has not cited, and we have not found, any Colorado precedent holding that an appearance of bias arises whenever a judge presiding over a criminal case has experienced criminal conduct similar to the conduct at issue,” wrote then-Judge David J. Richman. He added Hughes’ encounter was too remote and dissimilar from Sanders’ trial to give even the appearance of bias.

Judge Ted C. Tow III wrote separately to emphasize that a judge’s appearance of bias could lend itself to reversal of a defendant’s convictions, but it was unnecessary to figure out when that might happen.

Appearing before the Supreme Court, public defender Tracy C. Renner proposed looking at a variety of factors when asking whether a judge who was the victim of an unrelated crime would seem biased to the point that the defendant did not receive a fair trial. Further, Sanders’ trial lawyer did not have the ability to fully investigate the details of Hughes’ revelation.

“I’m definitely not suggesting judges have some obligation to disclose in every case any possible situation that might pose a potential for bias,” she said. “But where we know about it, where the judge themselves has brought it to the attention of the parties, there should be an opportunity for further explanation.”

First Assistant Attorney General Paul Koehler countered that a judge’s life experiences are not grounds for challenging a criminal conviction.

“There is a lot of faith within the system in how trial judges run their courts. It would break down otherwise,” he said. “Appearances should not matter. If they matter, they have to be tied to actual improper conduct.”

“Your framework seems a little binary. Actual bias, and nothing else,” observed Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter.

“I’m concerned about how strong that rule is,” agreed Justice Richard L. Gabriel. He referenced other cases involving an elected judge who took large campaign contributions from a litigant before his court and a federal judge in Colorado who had to address his impartiality after his son was murdered.

“Your position would be: Unless the judge is actually biased, that’s not even relevant to argue an appearance of partiality. I guess my question is why would that be true?” Gabriel asked. “Don’t we care that a judge has a strong appearance of partiality?”

The case is Sanders v. People.