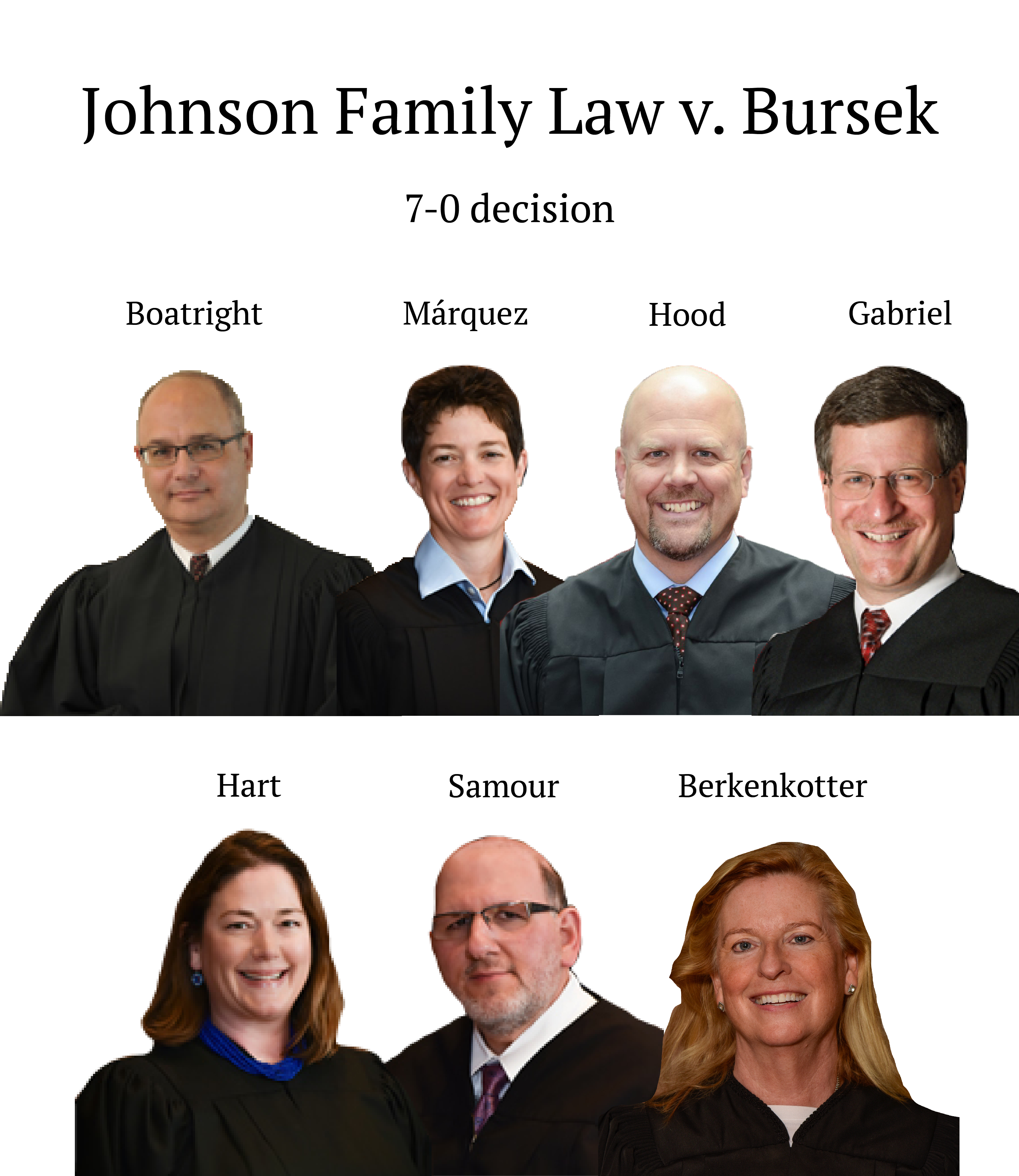

Colorado Supreme Court draws line on financial penalties for firm-switching lawyers

Law firms may not require departing attorneys to pay a fixed amount for every client they take with them, unconnected to the firm’s actual expenses, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled on Tuesday.

Under the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct for attorneys, law firms generally cannot enter into an agreement that “restricts the right of a lawyer to practice” upon leaving a firm. The purpose of the rule is to preserve an attorney’s professional autonomy and to avoid interference with attorney-client relationships.

For the first time, the Supreme Court examined whether law firms violate the rule by requiring attorneys to pay a preset financial penalty for each client who goes with them when they switch companies. The court answered in the affirmative.

“An agreement that requires a lawyer to pay a former firm such an undifferentiated fee is fundamentally at odds” with the rule, wrote Justice Melissa Hart in the Jan. 16 opinion. “Of particular concern, such a fee forces attorneys to make individualized determinations of whether a client is ‘worth’ retaining and incentivizes them to retain clients in high-fee cases and to jettison clients with less lucrative claims.”

She added that not all financial penalties are forbidden, as law firms may legitimately ask lawyers to repay specific costs attached to certain clients. However, that was not what happened when Grant Bursek left his job at Modern Family Law.

In March 2019, Bursek became an associate attorney at Modern Family Law. He entered into an agreement to reimburse the firm for marketing expenses if he left and took clients with him. Instead of client-specific costs, the agreement committed Bursek to paying $1,052 per client based on the historical marketing average in the Denver area.

When Bursek left Modern Family Law six months later with 18 clients, the firm billed him. Bursek did not pay, prompting Modern Family Law to sue him for nearly $19,000.

The Court of Appeals, in reviewing the agreement, believed some penalties are permissible to ensure the financial health of law firms, but the fee cannot be so exorbitant as to force lawyers to end relationships with their clients.

Judge Terry Fox wrote in the three-judge appellate panel’s opinion that Modern Family Law’s fees were unreasonable because, at $18,936, they restricted Bursek’s ability to practice law.

“It was entirely reasonable for Bursek’s clients to follow the lawyer they trusted,” she added. “That the Agreement restricted his clients’ mobility within such a sensitive practice area weighs further against its reasonableness.”

During oral arguments before the Supreme Court, Modern Family Law warned the financial health of law firms would be imperiled if they spent money marketing themselves to clients, only for those customers to follow their attorneys elsewhere when they switch firms.

“I worked in a law firm. It was frustrating when you invested a lot of money in someone and they left,” Justice Richard L. Gabriel acknowledged. “But that’s just kinda the cost of doing business.”

The Supreme Court declined to adopt a blanket prohibition against financial penalties for departing lawyers. Costs tied to a specific client may be reasonable, Hart explained.

What is unreasonable, she added, are fees “based not on specific spending for a client but (those) imposed without any individualized assessment.”

“While today’s decision was clearly a win for me, more importantly, it was a substantial victory for clients,” said Bursek. “Moving forward, a client will not have to worry that their relationship with their trusted attorney could be jeopardized due to a lawyer needing to unjustly financially compensate a law firm.”

An attorney for Modern Family Law did not respond to an email seeking comment.

A signal to the Court of Appeals

The Supreme Court also admonished the Court of Appeals for its handling of the case, putting the state’s second-highest court on notice to watch how it decides future appeals.

Hart explained the appellate panel addressed an issue the parties had not raised: whether Bursek’s employment agreement was void in its entirety, or just the portion imposing the fixed fee. The Supreme Court chose to review that portion of the panel’s decision unprompted – even as Hart criticized the appeals court for doing the same thing.

The Court of Appeals may not “address issues not presented by the parties without offering some clear justification for doing so,” Hart warned. “In the absence of such a justification, the court may not consider the issue.”

She added that the “fairness of the judicial proceeding” required the Supreme Court to intervene in the absence of a formal request.

Attorneys told Colorado Politics it was reasonable for the Supreme Court to emphasize that appellate judges should generally not go beyond the issues argued by the litigants.

“On the other hand,” said appellate attorney Meredith O’Harris, “the ‘substantial justification’ language is definitely new.”

She predicted Hart’s warning would provide ammunition for parties to seek Supreme Court review if the Court of Appeals again oversteps its boundaries.

The case is Johnson Family Law v. Bursek.