Homeless and jobless, immigrants ask Denver City Council to help them get work permits

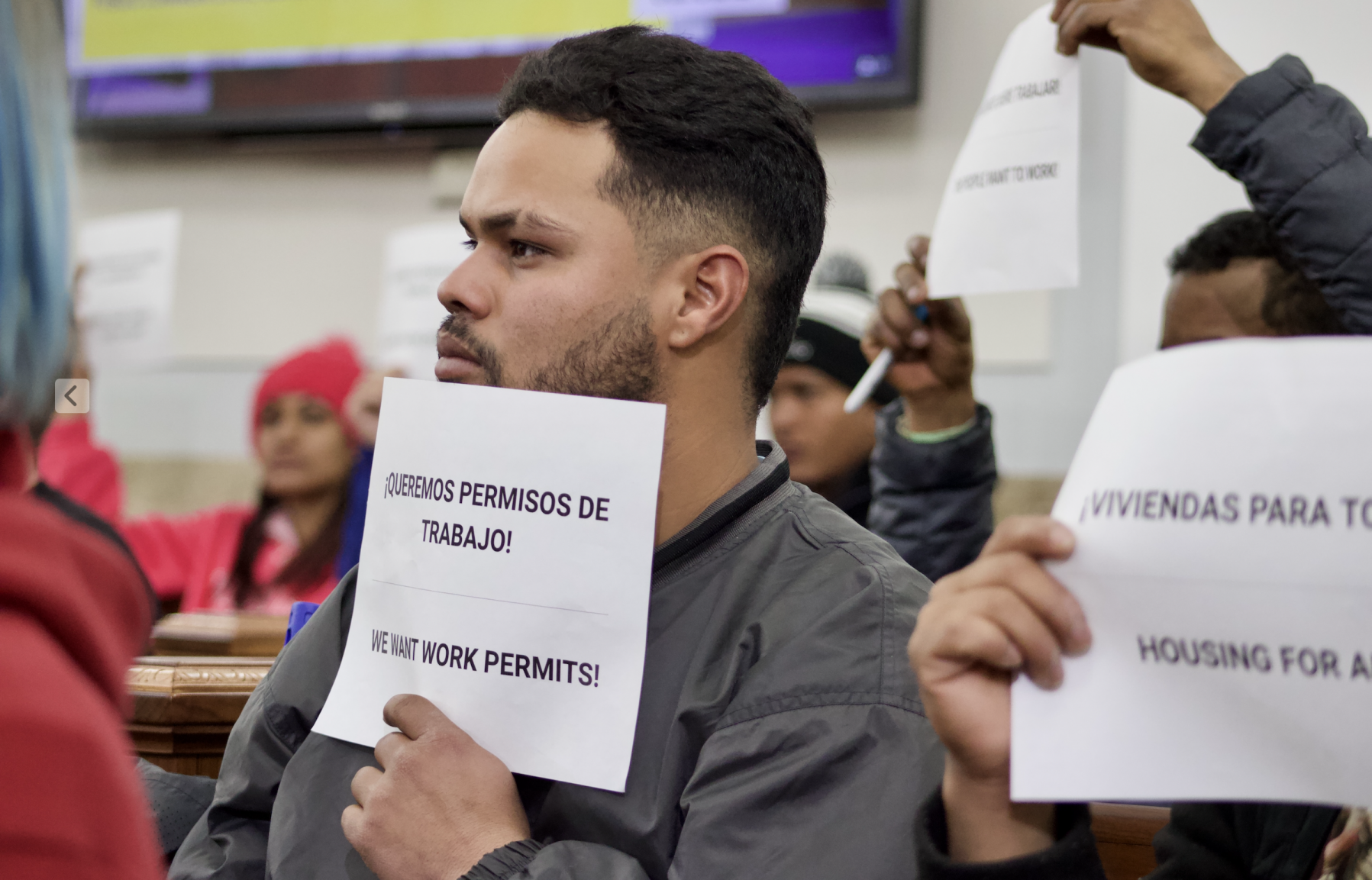

Dozens of immigrants who crossed America’s southern border illegally and now live on Denver’s streets showed up at a City Council meeting Tuesday, pleading with the local officials to help them obtain work permits.

They were among the nearly 36,000 immigrants – the majority from South and Central America – who arrived in Denver within the past year, yet another stark manifestation of the border crisis that so far has cost Denver’s taxpayers $36 million.

The crisis is unfolding at a time that the city is already struggling with homelessness. Denver has spent $45 million in the last few months to house more than 1,000 of its own homeless population.

“We are homeless. We have families,” Alex Vargas, a Venezuelan immigrant, told councilmembers during the policymaking body’s meeting on Tuesday night. “All we want is to work and to integrate into society.”

Granting a work permit is the sole purview of the federal government.

Some immigrants apologized to councilmembers for “inconveniencing” the city. Meanwhile, the advocates who accompanied them insisted that they be given more time to speak.

That the immigrants showed up at City Hall hints of political organization and desperation, as hundreds find themselves on the city’s streets in winter time, when the temperature plummets to below freezing. They are also largely dependent on city government and nonprofit agencies for food and necessities.

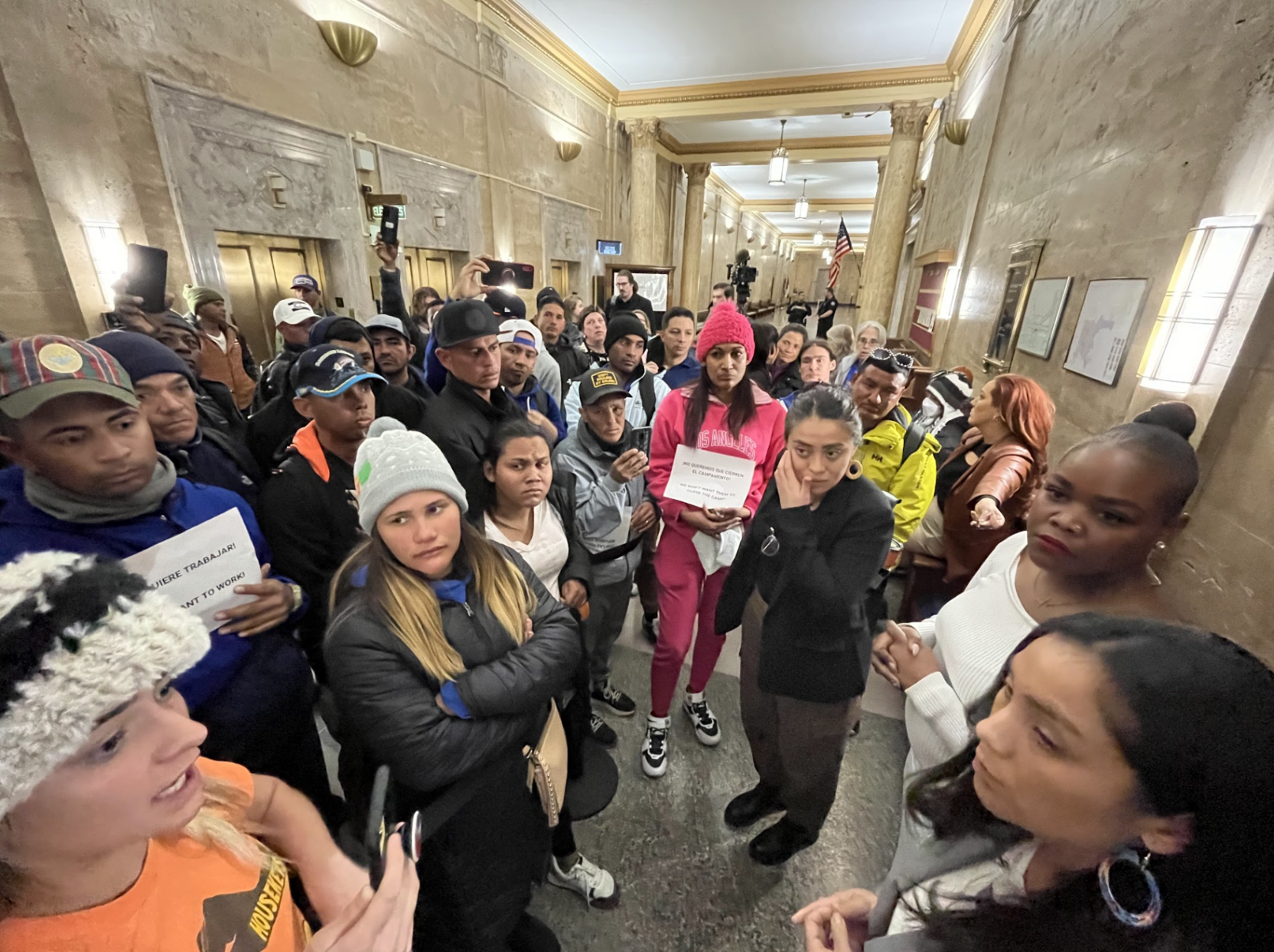

District 8 Councilmember Shontel Lewis and at-large Councilmember Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez temporarily left the council meeting to talk to the immigrants in the building’s hallway, where roughly three dozen congregated.

The councilmembers told the group that work permits are the responsibility of the federal government.

“What we can do is work with our federal delegation to maybe move that process along faster,” Lewis told the immigrants. “We discussed drafting a letter that we can send to the federal delegation on behalf of this entire body.”

Councilmembers said they would urge Denver Mayor Mike Johnston to do the same.

“I just want you all to know that there are many of us, probably almost all of us on this council, who are trying really hard to find the funding, to find the resources,” Gonzales-Gutierrez said. “I just want you to know that we’re not going to give up on you. We hear you that you want to work. And that’s what we’re trying to figure out is what that path is.”

Many of the immigrants who attended the council meeting came from the encampment off Speer Boulevard and Zuni Street, which the Johnston administration closed on Wednesday.

Over the past year, nearly 36,000 immigrants have arrived in the city, which has spent $36 million – and counting – for food, shelter and transportation. While the city has received roughly $14.1 million in state and federal funding, Denver taxpayers have assumed the brunt of the costs.

Roughly 4,500 immigrants were being sheltered in Denver as of Tuesday.

Early in the crisis, officials determined the city would pay to temporarily feed and house the new arrivals and transport immigrants who do not want to stay in Denver to the destination of their choice.

While city leaders have estimated 70% of these new arrivals do not intend to stay in Denver, officials have purchased bus, plane and train tickets for less than half.

Obtaining work authorization for the immigrants can take months – for those who qualify.

Juan Carlos, a Peruvian immigrant, told The Denver Gazette he traveled across jungles and eight countries just to get to Denver and join his family.

“We sacrifice a lot of things to be here,” Carlos said. “I am thankful with the country letting us inside, but it’s not good. They say we cannot work.”

Carlos said he lived in an immigrant shelter, and was given 37 days but was kicked out after 30 days. Under Denver’s rules, single, immigrant adults can stay at a city shelter for two weeks, while those with children have up to 37 da

Johnston said all immigrants displaced from the immigrant encampment sweep would be offered temporary shelter.

Many of them had stayed at city shelters before but ran out of vouchers.

Last month, Denver marked a year since about 90 immigrants were dropped off at Union Station downtown, left to wander in the cold. Officials have scrambled ever since to respond to the growing crisis.

The latest waves of new arrivals started in the fall when the number crossing at the southern border with Mexico began to swell and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott started sending immigrants to states with Democratic governors.

As of Dec. 29, Abbott has sent 13,800 to Denver – more than Philadelphia and Los Angeles combined – including a “ghost bus” that dropped immigrants off at the Colorado state capitol. Officials have speculated that immigrants are drawn to Denver because of its relative proximity to the Mexico border, while others believe its status as a “sanctuary city” is the appeal.

Just last week, Johnston joined the mayors of New York City and Chicago to bemoan Abbott’s tactics, while calling – again – on Congress to address the surge at the U.S. border with Mexico.

Renae Eze, an Abbott spokesperson, called out the duplicity of the mayors.

“The sheer hypocrisy of these Democrat mayors knows no bounds,” Eze said in an email to The Denver Gazette. “They are now going to extreme lengths to avoid fulfilling their self-declared sanctuary city promises, yet they remain silent as President Biden transports migrants all around the country and oftentimes in the cover of night.”

Johana Gonzalez, an immigrant from Venezuela who is looking to further her training in nursing, said, “We come from tropical weather and just arriving in Denver and living in zero degree weather – it’s not human.”

“We are here to add to the economy, not just to take away from it. We just want opportunities to continue learning and growing here,” she said.