Douglas County judge wrongly let man represent himself, appeals court rules in reversing convictions

A Douglas County judge was wrong to let a man represent himself at trial without ensuring he understood the basic elements of his case first, Colorado’s second-highest court ruled on Thursday in overturning the defendant’s convictions.

The Court of Appeals’ decision was the second time this year it ordered a new trial for David Antonio Ruffin based on how various trial judges responded to Ruffin’s insistence that he wanted to proceed “pro se,” or without an attorney.

In August, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals reversed Ruffin’s convictions for assault and indecent exposure in the Arapahoe County jail because the trial judge did not adequately advise Ruffin about the consequences of proceeding pro se, nor did he account for Ruffin’s mental illness when allowing Ruffin to give up his constitutional right to counsel.

The most recent case to reach the Court of Appeals bore some resemblance to those flawed proceedings.

Case: People v. Ruffin

Decided: October 26, 2023

Jurisdiction: Douglas County

Ruling: 3-0

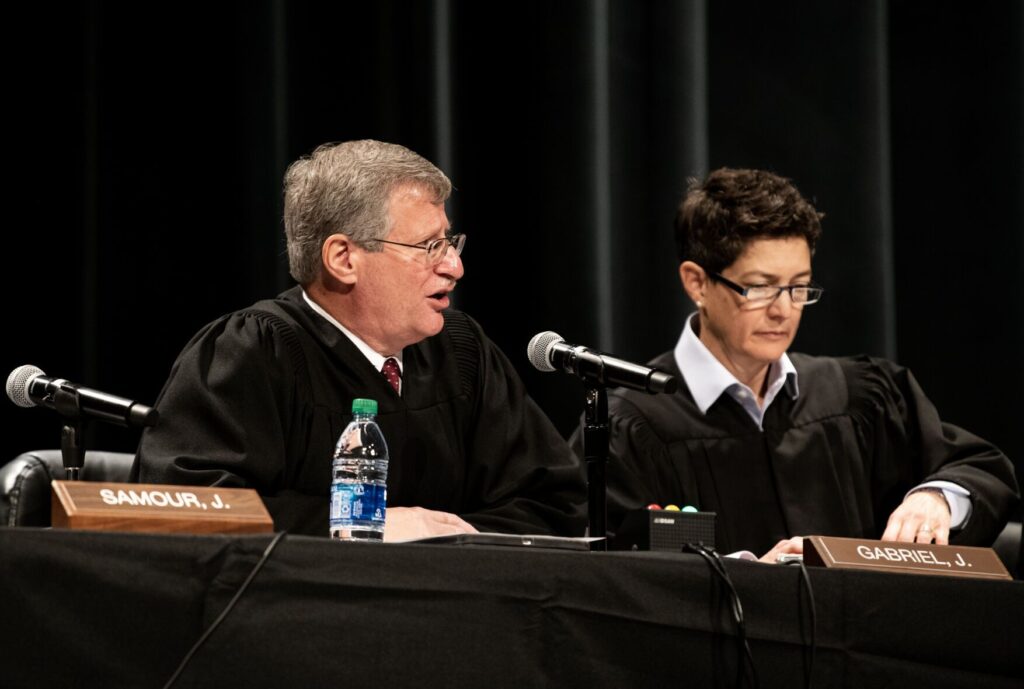

Judges: David H. Yun (author)

Rebecca R. Freyre

W. Eric Kuhn

Background: Appeals court overturns convictions of mentally ill man who represented himself

Ruffin was in the Arapahoe County jail when he allegedly developed a fixation with a female sheriff’s deputy. Ruffin would later contend the deputy was equally interested in him, but after Ruffin’s release, the deputy reportedly became concerned about Ruffin’s attempt to contact her.

One day, Ruffin showed up at the deputy’s house and spoke with her father. Ruffin’s presence frightened the deputy, who called 911. Police arrested Ruffin and he became subject to a protection order, also known as a restraining order. Nonetheless, he continued his attempts to contact the deputy, acknowledging in one of his letters that he was doing something “super illegal.”

Douglas County prosecutors charged him with more than a dozen offenses. Ruffin insisted upon not having a trial by jury, and District Court Judge Patricia Herron found him guilty on all counts in 2020. She sentenced him to 14 years in prison.

Ruffin first raised his desire to proceed without an attorney in late 2019 because he had a “fundamental disagreement” with his lawyer. County Court Judge Lawrence Bowling told Ruffin his options were to keep his appointed lawyer, hire another one or go to trial pro se. Bowling cautioned that “it’s always better for someone to have an attorney,” but permitted Ruffin to represent himself.

Months later, Herron, who had taken over the case, double checked whether Ruffin still wanted to proceed pro se. Ruffin said he did and tried to explain his reasons, but Herron said she did not need to hear them.

Although Herron did subsequently tell Ruffin he would be better off with an attorney, Ruffin ended up representing himself at trial.

On appeal, Ruffin’s attorney – before Ruffin decided he wanted to proceed pro se again – argued trial judges are required to ensure a defendant gives up their right to counsel voluntarily, knowingly and intelligently. Although judges do not have to recite the list verbatim, there are more than a dozen questions they should ask, covering the defendant’s understanding of legal procedure, knowledge of his rights, and the specific charges and penalties he faces.

“The totality of the circumstances as revealed in the record here makes it clear that Mr. Ruffin, in addition to not being properly advised as to the risks inherent in waiving his constitutional right to counsel … simply did not have a rational or factual understanding of the proceedings against him, or indeed, a grip on reality,” wrote attorney Mallika L. Magner.

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office countered that Ruffin had been found competent to stand trial and was able to question witnesses effectively, which showed his “fulsome understanding” of the case.

The Court of Appeals was not convinced. Even if Ruffin was aware of the subject matter by the time of trial, explained Judge David H. Yun in the Oct. 26 opinion, nothing showed Ruffin’s understanding at the time he gave up his right to an attorney.

“Without the court’s on-the-record advisement of such basic information as the charges and the maximum range of punishment that could be imposed, we cannot conclude that a knowing and intelligent waiver of counsel occurred,” wrote Yun, who also authored the prior decision reversing Ruffin’s convictions in Arapahoe County for similar reasons.

The appellate panel found Ruffin could be retried on his charges, as the evidence supported a guilty verdict. Specifically, for Ruffin’s two stalking convictions, the Court of Appeals agreed Ruffin’s actions appeared to cause the deputy “serious emotional distress,” as Colorado law requires.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Supreme Court found Colorado’s stalking statute was defective to the extent it did not account for an alleged stalker’s intent. Ruffin did not raise a challenge to the constitutionality of his stalking conviction, nor did the Court of Appeals directly address the Supreme Court’s decision.

The case is People v. Ruffin.