A 1,200-year-old water concept flows through Colorado’s Costilla County

COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. In the small, idyllic town of San Luis, which sits near the foot of a fourteener, people grow their own food, a tradition that goes back generations, long before Colorado became a state.

For residents who live in properties located in the heart of the community of 750 people, irrigation for the family gardens comes through a ditch, with each house plated on a strip of land, sometimes no more than 50 yards wide, that includes space for the home, outbuildings, the garden and livestock.

The streets of San Luis, which boasts of being Colorado’s oldest continuously occupied town, are lined with homes on those strips of land, with the water channel in the backyard and sometimes in the front yard.

But that water doesn’t belong to just one property owner who might hold a more senior right than a neighbor or someone further downstream.

In San Luis, and the small towns that surround it, water rights are held by ditches that were built before Colorado became a state – and under a concept that seems almost foreign to the rest of the West, which lives on the laws of prior appropriation, meaning “first in time, first in right.”

The West’s prevailing premise, in effect, means the first person to claim the water gets the most, and everyone else likely gets a little or lot less.

But, as it turns out, this communal water management concept in Costilla County came from lands very far away. And from an approach that is very old.

The concept called “acequia” dates back to the days of the Spanish Moors, when Muslims from North Africa captured the Iberian Peninsula – today’s modern Spain and Portugal – and ruled parts of what was known as al-Andalus. That time produced great centers of learning and magnificent art and architecture, as well as attracted scientists and philosophers from the known world.

The Moors ruled al-Andalus from the early 8th to the late 15th century.

And it was the Moors who brought the idea of irrigation canals – “as-saqiya” in Arabic – to Spain, although some researchers believe the Moors may have borrowed on similar systems dating back to the Romans.

Spanish explorers transported the idea to Mexico, where it was carried into New Mexico by Hispano settlers, people of Spanish origin who later migrated to Colorado prior to the end of the Mexican-American War and before annexation of the Colorado territory into the United States.

Luis Pablo Martínez Sanmartín, writing for a 2020 report on “Acequias of the Southwestern United States,” said the concept survived through the centuries because “of their common-good oriented design that is based on principles, such as cooperation, water sharing, respect, equity, transparency, fairness, mediation, negotiation, proportionality between water allocation rights and systemic maintenance duties, and solidarity.”

Acequias have more benefits than just irrigation. One paper cited their positive influences on ecosystems “by increasing floral and faunal biodiversity, extending the riparian zone, and protecting the hydrology and ecology of the watershed.”

In contrast, the dominant property rights-based premise almost everywhere else in Colorado means a perennial battle over who gets how much from a ditch, river, stream or aquifer.

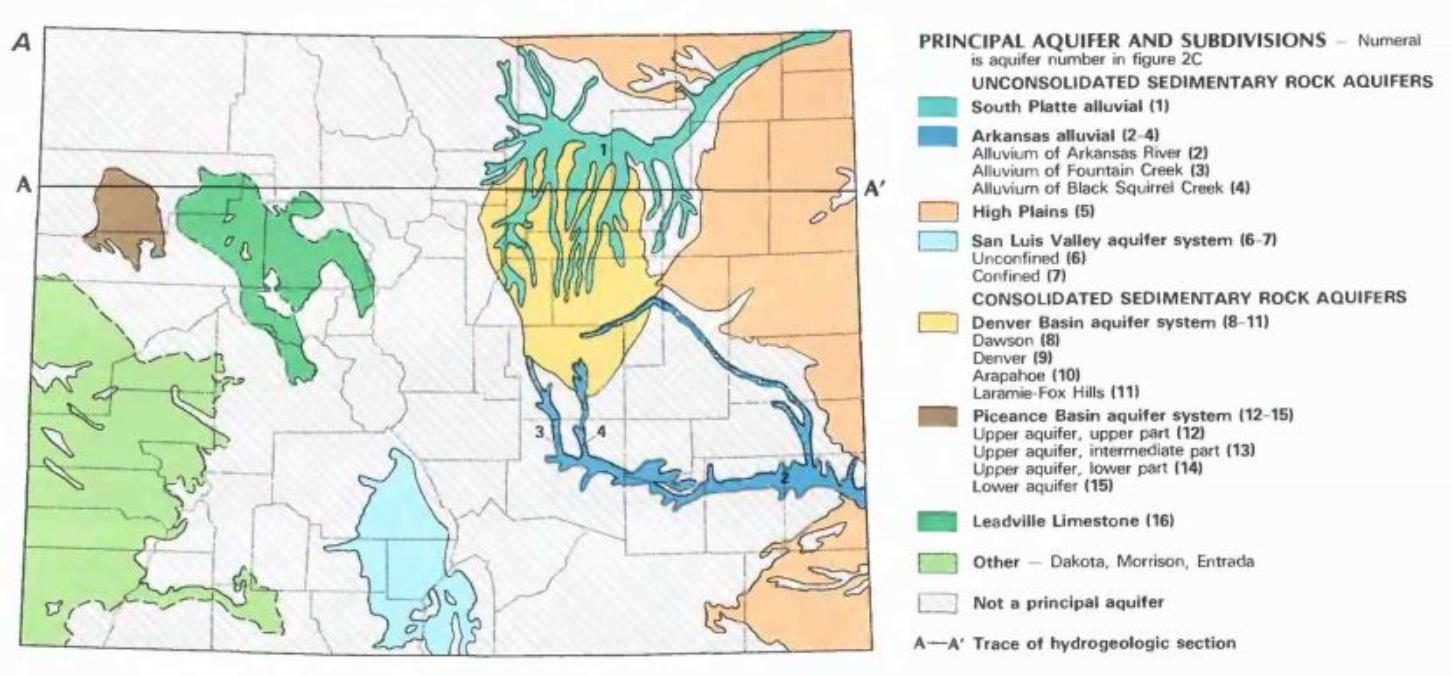

Costilla County sits on the edge of the most battled-over aquifer in the state: the unconfined body of water found under the six counties of the San Luis Valley.

Residents of San Luis say the fights over the aquifer, where 22,000 acre-feet of water is being sought by a Douglas County-based company that is offering big bucks for water rights, is not high on their radar right now.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

But they’re watching those fights warily, while working to protect their water flowing through the acequias, should the day come when someone offers to purchase that water out from underneath them.

Today, more than 70 acequias can be found in Costilla County and – thanks to the work of lawmakers, as well as faculty and students at the University of Colorado Boulder law school – over the past 15 years, most have now been legally adjudicated and under protection well into the future. Those protections, from a 2009 statute, also extend to Huerfano, Las Animas and Conejos counties, although only a few acequias operate in those areas.

How acequias work

The acequias of Costilla County allow snowmelt coming off Culebra Peak, the world’s highest privately-owned fourteener, to slow as the runoff travels through Culebra Creek and into the miles of ditches that intersect with the creek.

The New York Times in July described a similar system in Spain this way: “Without acequias, snowmelt from mountain peaks would flow directly into rivers and lakes that dry up during the summer. With them, the melt is diverted to multiple acequias winding through the hills. The water soaks into the ground in a ‘sponge effect,’ and then circulates slowly through aquifers and shows up months later, downslope, in springs that irrigate crops during the dry season.”

In the four counties with acequias, farmers, ranchers and other landowners along an acequia form an association, sharing a common stream diversion, a hand-dug “mother ditch,” which then channels water to individual properties. The participants pay dues, contribute to the cleaning and maintenance of the ditch, and annually elect a ditch manager or “mayordomo,” who has a lot of say about how water is equitably distributed along the ditch.

Acequias serve a purpose more than just bringing in water: They reflect cultural history and traditions.

Drive along the roads around San Luis and you come to towns with names like Chama, San Pedro, San Pablo and San Francisco. Today, it’s a short drive, just minutes between towns, but 100 years ago or more, the acequias named for their towns connected those towns and cultures.

Gregor MacGregor, director of the Acequia Assistance Project at the University of Colorado law school, described it this way:

“Acequias are more than just a water delivery system, they represent a culture and form of governance rooted in equity and fairness, expressed in the requirement that labor on the ditch is shared and in the ability of each family to cast a single vote, regardless of the amount of land or water they use.”

The acequias of San Luis

Every year, snowmelt brings down water from Culebra Peak near the towns of central Costilla County into Culebra Creek, eventually finding its way into earthen structures that hold the oldest water rights in Colorado.

Those water rights go all the way back to the 1851 San Luis People’s Ditch.

Efforts now abound to save the acequia way.

“Water is life and life is water,” said Ronda Lobato during a recent visit by Colorado Politics to the town.

Lobato, the secretary of the Costilla County Conservancy District board, has been involved with the conservancy district for a dozen years. That’s just a fraction of the time her family has thrived in San Luis, now at seven generations, before there was even a Colorado, much less a San Luis, which brags of its status as the state’s oldest town, established in April 1851.

The acequias “protect our community’s way of life. We are blessed and have to take care of it,” she said.

The value of that way of life hit home during COVID, she said. Her daughter had gone away to college and wanted to head to Las Vegas after graduation. COVID changed those plans and she came home instead.

Then, she said, it dawned on her kids: They could stay home, grow their own food and live a different life.

Indeed, her kids realized they could sustainably live, with just their land and the water that irrigates it.

But Lobato had a problem. Somewhere in the recent past, her family’s historic home, which was on the Montez Ditch, no longer had rights to the acequia.

Enter the CU Acequia Assistance Project, a joint effort by the Getches-Wilkinson Center at the law school, Colorado Open Lands, and the Sangre de Cristo Acequia Association. The project aims to help acequias that didn’t have formal legal structures, such as incorporation or bylaws, and the legal protections that come with those structures.

MacGregor, now the director of the Acequia Assistance Project, first joined the endeavor when he was a law school student, figuring out he’d spend a couple of years on it, digging through dusty record books of land titles and deeds in the back room of the Costilla County government building in preparing an acequia for legal protection.

Time flew by. That was nine years ago. He’s hooked on acequias, as are dozens of law students who follow him to San Luis every year. The project has since extended from doing the legal legwork – drafting bylaws for the associations or representing the acequias in water court – to education and even helping to look for grants to help pay for some of the projects tied to the acequias.

MacGregor and his students discovered a previous owner of the property had sold the house but kept the water rights and then passed them on to his children when he died. MacGregor and his students worked with the landowner’s family to sell the water rights back to Lobato and her family, a process that, from beginning to end, took about three years.

Those water rights had little monetary value, but meant much more to the Lobatos in terms of culture and history, he said.

Not everyone comes back

The acequias bring water from the peaks to the valleys in a seemingly endless cycle, quenching the thirst of towns but not always the desire of younger residents pining for a life outside, out there in the big city, where things move faster.

Indeed, not everyone stays or comes back to San Luis, where flags fly along the main street, honoring the original settler families, names such as Lobato, Gallegos and Jaquez.

Charlie Jaquez, something of an unofficial town historian, is related to one of those original families. He talked of speaking Spanish before he learned English, and how he taught in the San Luis school for more than 30 years.

“Rural Colorado kind of just suffers quietly because we don’t have money,” he said. “And the reason we don’t have money is we just don’t have very many people.”

He has two sons, but neither is coming back to San Luis. One, an emergency room doctor in Fort Worth, Texas, wants to, but carrying almost a quarter-million dollars in student debt means that won’t happen anytime soon.

Still, there are bright points, Jaquez said, pointing to folks like Lobato, a former student, who he called “sharp” and someone he said is keeping the community alive.

That includes Lobato’s efforts to come up with a recreation center for the area.

“There’s no place for kids after school or on weekends,” she said.

That’s in part led to the creation of Soul Players of the Valley, an effort centered around four communities in the valley that intends to “build or revitalize community centers to prioritize youth enrichment and development, expand health services, especially for mental health and substance use, improve economic conditions, and preserve and celebrate our culture.”

Protecting the acequias

Frank Vigil keeps an eye on the San Pedro acequia, which he says irrigates about 1,800 acres in the area.

“We’ve always irrigated from this,” he said recently. “We’ve had historical access to this water” since before the first set of decrees in 1889. His family has owned the land, now his, for generations – it was his parents before him and their parents before that.

“Water is the most valuable thing on planet Earth,” Vigil said. “You can’t go but a few days without water … it sustains life. Its boundaries wherever water touches, things live.”

Vigil said the water coming through the acequias almost never reaches the Rio Grande.

“Given enough scarcity, somebody’s going to find a way to put a straw in that and move it around,” he said. “We have to do what we can in order to ensure that this stays here and tied to our land.”

Vigil’s worry permeates the community.

It’s the same concern that animates Colorado Open Lands, which advocates for conservation easements to protect ranch and farmland from development, has been involved in the San Luis Valley and its acequias for over a decade, according to Joel Nystrom, who works on San Luis Valley acequias. The organization got interested in acequias out of concerns for protecting Colorado’s oldest water rights. That includes the San Luis People’s Ditch, which holds Priority No. 1 and which has two easements. More of the state’s oldest water rights are nearby, all on acequias, and easements are being put on those acequias, too.

“It’s much more based on shared scarcity and water being treated as a community resource rather than a commodity,” Nystrom said.

Putting conservation easements on acequias keeps the water flowing and protects them in perpetuity, Nystrom explained. That should keep the water out of the hands of anyone who would come calling with enticements, often big dollars that might be difficult to resist. It’s not an immediate threat but there’s definitely a potential for one, he said.

“We’re hoping to get ahead of that,” he added.

What else needs protecting? The watershed itself, the source of the water coming off Culebra Peak.

That’s been Lobato’s passion for the last several years, and one that recently came to fruition with the conservancy district’s first watershed assessment.

The 844-page assessment found a myriad of serious problems: degraded riparian habitats, flood hazards, issues with water quality tied to a nearby closed gold mine and elevated mercury and arsenic levels in nearby Sanchez Reservoir.

Lobato noted 40 priority projects that could come from the assessment, which identified six priority areas:

-

Improve community safety and reduce overall community risk from natural hazards

-

Improve water quality

-

Reduce conflict or improve conflict resolution related to natural resources

-

Fill in data gaps identified from the technical sections of this report

-

Increase water yield or water availability

-

Improve aquatic habitat

The mountain and the Morada

The “common good” embedded in the culture of the acequias isn’t just about the water or ditches. It extends into other aspects of community life, what Sylvia Rodriguez refers to as the acequia’s “moral economy” or the interdependence that results from being part of the acequias culture.

One of the better demonstrations of what the moral economy looks like is in the small town of San Francisco, just a few miles away from San Luis.

On the town’s edge sits one of Colorado’s last active Moradas, a Catholic chapel and meeting house.

For more than 150 years, every spring, during the week of Good Friday, residents of the area walked the “stations of the cross” on the hill behind the Morada, led by a “hermano penitente,” a layperson in the Catholic church who holds ceremonies and performs other functions in the absence of a priest.

But the Morada faces an uncertain future, the result of destruction to the hillside behind the building, caused by what locals claim is an illegal and poorly-constructed fence intended to keep bison on the private ranch on Culebra Peak and locals away from hunting or gathering firewood, something they insist they’ve had the right to do for decades.

Cielo Vista Ranch covers 23 miles and 83,000 acres along the Sangre de Cristo mountains, including Culebra Peak, which locals call La Sierra.

In the 1960s, the owner, Jack Taylor of North Carolina, began erecting a fence to keep the residents off the property.

Lawsuits quickly followed.

In 2002, in a decision called “shocking” by many, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Costilla County residents for their right to access La Sierra for grazing pasture and timber, but not hunting. The lawsuit, Lobato v. Taylor, was the longest-running legal case in the state, and finally concluded in March 2022, with a decision putting in place a mediator, Judge Kenneth Plotz, to help the two sides find resolution.

But the fight isn’t over. Not by a long shot.

The Costilla County commissioners declared a moratorium intended to prevent more fence construction, but the current owner, a Texas oilman named William Bruce Henderson, keeps adding to it, arguing it is intended to keep in his bison herd.

The fence’s expansion caused erosion on the hill behind the Morada, according to MacGregor. History Colorado stepped in and paid for a concrete wall to stabilize the hillside, but the residents worry that more fencing means more trouble.

Today, to get onto the land behind the fence, one must have a key to the fence gate, and that’s how those who want to climb the hill for the Good Friday ceremony get to their traditional place of worship, which includes a hole for a cross. Abut 350 families have keys to the gates.

Henderson attempted to buy the access rights back for $300 per family. His ranch manager complains about vandalism, fence gates torn down and other problems on the mountain he attributes to local residents.

Arnie Valdez, one of the few remaining hermano penitentes in the San Luis area, says his family goes back five generations on land outside of Chama. At one point it was 70 acres, but he now farms about 15, plus another five that’s fallowed.

His major crop is bolita beans, a small, round, and sweet bean native to the area and which he inherited from his father. Growing beans is a time-consuming process, one that requires him to be vigilant.

Valdez is not optimistic about the future of the Morada or the brotherhood tied to it.

“We’re the last brotherhood here in Colorado,” he said. One other Morada exists in the town of Garcia, southwest of San Luis.

With a lack of interest from young people, Valdez said he believes his brotherhood generation will be the last.

In a similar way, the future of the acequias hangs in the balance. Colorado, like much of the West, faces an acute water shortage, driven largely by overconsumption of the Colorado River and a drought that has plagued the region for decades. And while there is a vigorous effort to sustain the acequia way of life, that ultimately depends on the younger generation’s willingness to go back to their roots.

“We’re on the fringes out here,” Valdez said, “so that’s why it’s easier for us to lose the traditions,” he said.