Colorado Supreme Court says Boulder officer acted reasonably in asking driver to take blood test

The Colorado Supreme Court on Monday agreed a Boulder police officer acted reasonably when he asked a driver who crashed into and severely injured another man to take a blood test, then gave him substantial time to discuss it with his mother.

Eli Allan White was driving an unfamiliar Tesla and was preoccupied with the vehicle’s controls when he slammed into a man whose own car was broken down. White pinned the man between the two vehicles and caused the victim’s legs to be amputated. Although police believed distracted driving was the cause, they nevertheless asked if White would take a chemical test for intoxication.

The results came back positive for tetrahydrocannabinol, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana. A Boulder County trial judge, however, blocked prosecutors from using those test results, concluding police unreasonably extended White’s detention by seeking a blood test without any reason to suspect impairment.

“For multiple reasons, the officers understandably focused on White’s distraction from the road at the beginning of their investigation,” acknowledged Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. in the Supreme Court’s June 26 opinion. However, the request for a blood draw “was part of the one and only investigation into the cause of the collision, White’s role in the collision, and the crime or crimes he may have committed.”

Prosecutors appealed the ruling of District Court Judge Patrick Butler directly to the Supreme Court, as state law permits. They argued if it was constitutionally unreasonable for police to simply ask a suspect to consent to a blood test, law enforcement would have a more difficult time investigating car crashes.

On Jan. 3, 2022, White was driving along Broadway. It was the middle of the day and weather conditions were good. However, White was manipulating the screen on his father’s Tesla and did not see the victim’s car, stopped in the road, until it was too late. The victim was at the rear of his vehicle and suffered severe injuries from being pinned between both cars.

Officer Joseph Clemen arrived first and noticed White had red eyes and “constricted pupils,” but he attributed it to White’s extreme distress and crying. Clemen allowed White to call his mother and also requested a victim advocate attend to White. Clemen asked if White was under the influence of drugs, and White responded he had only taken medicine for depression and anxiety.

Clemen consulted with two other officers who had begun to perform accident reconstruction. He said he had no indication White was intoxicated. The officers agreed distracted driving appeared to be the cause, but one of them suggested Clemen ask about White’s sleeping schedule and if he would agree to a blood draw.

Returning to White, Clemen indicated White was not able to leave just yet. He inquired about White’s sleep schedule, which was normal, and about White’s willingness to do a chemical test. He said there would be no consequences for refusal. Clemen later testified he was simply trying to “back up” White’s statements, and “not to find any incriminating evidence.”

White called his mother, then agreed to a blood test. Clemen waited until the mother arrived, and clarified the voluntary nature of the request. The mother disclosed White used marijuana, but Clemen assured her it would “show up differently” if it were not “actively” in White’s system. Again, White agreed to the test.

The results showed his THC content was well over the amount state law sets as the cutoff for presumed impairment. As a result, prosecutors charged White with felony vehicular assault, which involves operating a vehicle under the influence of drugs.

In February, Butler issued an order suppressing the test results. He reasoned White was subject to an investigatory stop, which allows police to investigate a crime if they have reasonable suspicion and their actions are related to that inquiry. Yet, Butler effectively saw two investigations: the first, where officers concluded distracted driving caused the crash, and the second, where police detained White further to get his consent for a blood test.

White “was detained so law enforcement could attempt to gain his consent for a blood draw when they lacked reasonable suspicion that his blood would reveal evidence of intoxication,” Butler wrote.

The district attorney’s office, on appeal, insisted that criminal investigations are “fluid” and it was unreasonable to expect police to adhere to a single, preliminary theory behind a vehicle collision. Moreover, Clemen had accommodated White and his preferences throughout his time on scene.

“Officers, investigating a violent and tragic vehicle collision, asked Defendant if he would voluntarily provide a blood sample and gave him as much time as he needed to consult with family members and decide,” wrote Senior Deputy District Attorney Ryan Day. “If this is unreasonable, what should officers have done differently?”

The Supreme Court, in reversing Butler, saw one continuous investigation that included both intoxication and distraction as potential causes. The officers would have been “derelict,” wrote Samour, if they neglected to test White’s blood.

“Considering the clear and sunny weather, the flat and straight surface, the generally dry road conditions, and the lack of any obstruction, simple carelessness was certainly a possible cause of the collision. But so was drug intoxication,” he added.

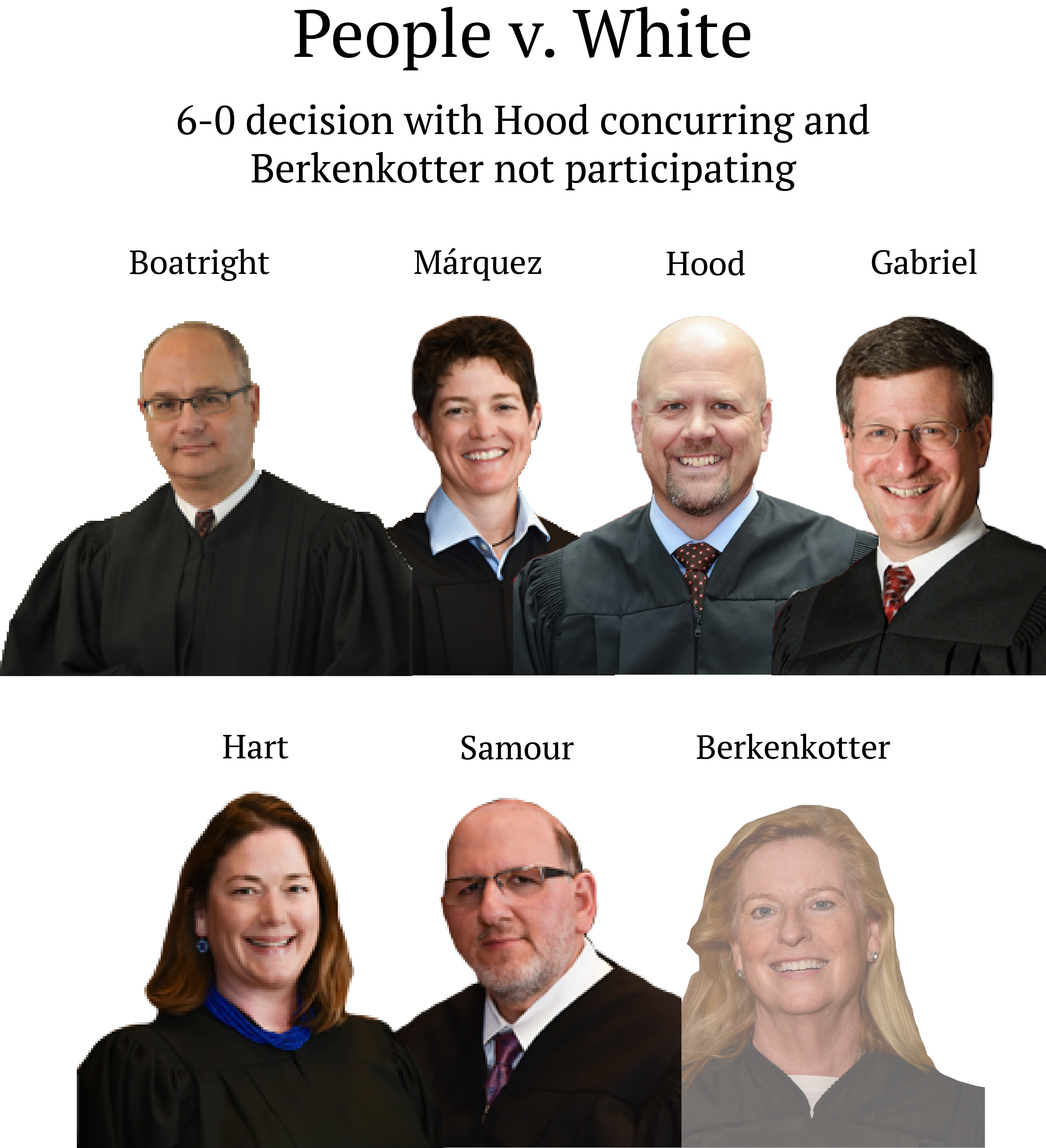

Justice William W. Hood III wrote separately to say that while he agreed Clemen acted reasonably, the court’s majority unnecessarily analyzed White’s own role in prolonging his detention and the police’s “diligence” in investigating. Hood believed officers already had probable cause for a crime – careless driving – and they would have been justified in arresting White, not simply detaining him.

Justice Maria E. Berkenkotter did not participate in the appeal. Clemen is no longer an officer, having been fired for concealing information to his supervisors outside of White’s case.

The case is People v. White.