Colorado appeals court reverses Adams County murder conviction due to judge’s faulty analogy

Colorado’s second-highest court on Thursday once again overturned a defendant’s conviction because an Adams County judge illustrated reasonable doubt to jurors in a way that improperly lessened the prosecution’s burden to prove him guilty.

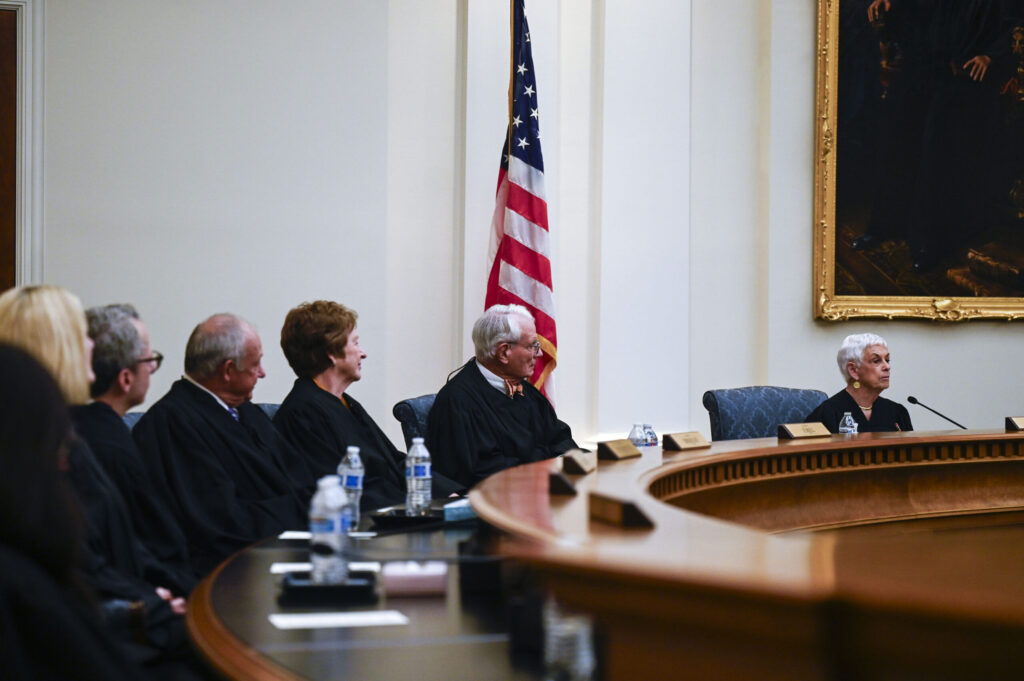

The Court of Appeals has repeatedly reversed the convictions of defendants for more than a year – exclusively from Adams County – after the Colorado Supreme Court decided last January that some judges’ well-meaning attempts to explain reasonable doubt in plain English actually lowered the threshold for a guilty verdict. Previously, the appellate court warned judges away from trying to liken reasonable doubt to everyday concepts, but some Adams County judges continued to do so.

The Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Tibbels v. People, which was the first time the justices reversed a conviction due to a reasonable doubt analogy, likewise arose from Adams County.

In Tibbels, a trial judge had compared reasonable doubt to the crack in the foundation of a “dream” home, suggesting a homebuyer would hesitate to purchase the house once they discovered the defect. The Supreme Court instead found the illustration made it seem as if the defendant was presumed guilty unless a significant “crack” appeared in the prosecution’s case to cause an acquittal. In reality, the opposite is true: Defendants are innocent until proven guilty.

The latest case before the Court of Appeals concerned the 2019 trial of Michael Kourosh Sadeghi, who shot and killed his neighbor, Dustin Schmidt. Sadeghi argued he was acting in self-defense at the time, but jurors rejected that claim.

During jury selection, District Court Judge Sharon D. Holbrook attempted to explain the concept of reasonable doubt by likening it to the purchase of a used car. She described finding a car “that you absolutely love,” where the “price is good” and “it is within your budget.” But on a test drive, there were noticeable defects. Would jurors still buy the car, Holbrook asked.

“I would have my doubts,” one juror responded.

“OK,” the judge continued. If the person selling the car was “a sweet little nun” and “you were not worried about her at all,” would the juror buy the car?

Yes, the juror responded. Holbrook added one more variation on the example, now asking whether the juror would buy the car if there was a problem with the transmission. No, the juror said.

“There is enough there that would cause you to hesitate to act in a matter of importance to yourself,” Holbrook explained. “If you think that there is too much wrong with this ‘car,'” meaning the case, then jurors had to acquit Sadeghi.

The defense objected to her analogy, calling it a “totally incorrect” statement of reasonable doubt. Holbrook overruled it.

Sadeghi appealed, alleging multiple errors with Holbrook’s handling of the case. In particular, he argued the used car illustration wrongly suggested to jurors that the prosecution’s case had to be “riddled with doubts” in order to find him not guilty.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals agreed Holbrook’s analogy, like the “dream” home example in Tibbels, likely caused Sadeghi’s jury to misunderstand when they should convict him. First, Holbrook made it seem that the prosecution’s case had to contain “significant” defects – equivalent to a car’s faulty transmission – for jurors to acquit.

Second, the jury instruction for reasonable doubt explains that a failure to prove even one element of the crime is grounds for acquittal.

“Here, though, the court’s analogy had several things wrong with the car, from minor to significant, which suggested that the jury needed to also have numerous doubts – and some significant ones – before they could acquit. But that is not the standard,” wrote Judge Sueanna P. Johnson in the panel’s May 25 opinion.

Finally, the analogy implied that buying the car – and finding Sadeghi guilty – was the default path unless there were concrete reasons to abandon the purchase – and to acquit him.

The Court of Appeals ordered a new trial.

The case is People v. Sadeghi.