Colorado’s courts by the numbers: 2022 in review

Following the COVID-19 pandemic’s disruption of the justice system, Colorado’s state and federal courts are still experiencing lower volumes of cases, with the drop being particularly acute for some courts more than others.

Colorado Politics examined the workloads of various courts in 2022, with the federal system reporting calendar year statistics and the state judiciary operating on a fiscal year that ends on June 30. In addition to trends in case filings, the analysis also looked at personnel changes on the bench, judicial retention and discipline, and the frequency of lawyers being paired with self-represented parties.

State caseloads

For the fiscal year that ended in June 2022, there were almost 200,000 case filings in the state’s district courts. That amounted to nearly 30,000 fewer cases than two years prior, when the novel coronavirus rapidly began to affect the judiciary and society at large.

“We have made progress in reducing our jury trial backlog, and we will continue to prioritize criminal jury trials as long as we can do so safely,” Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright wrote in the Judicial Department’s annual report. He added that virtual proceedings are more convenient for lawyers and litigants, “but they take more time for judicial officers and court staff.”

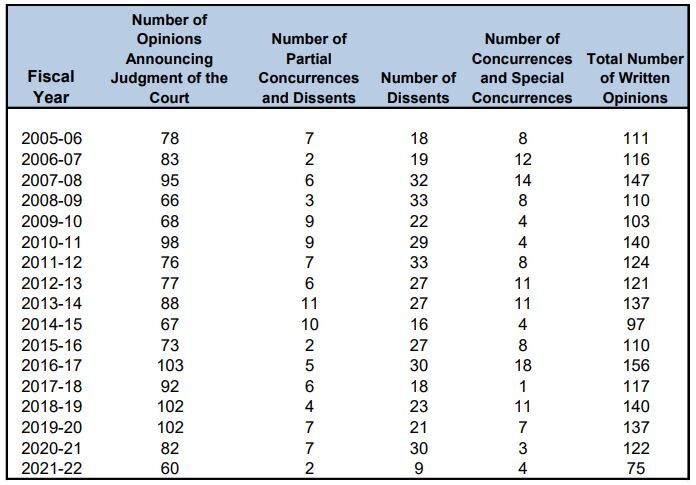

The state Supreme Court’s workload has taken a more serious dive. While there were 1,500 appeals filed in the last fiscal year – on par with caseloads stretching back decades – the justices only decided 60 cases with written opinions. That is less than the 82 decided in 2020-2021 and far fewer than the 103 decisions issued during 2016-2017.

Although Supreme Court opinions have declined by approximately 40% compared to pre-pandemic, the last fiscal year was the most harmonious in recent history. There were only nine dissenting opinions in 2021-2022 compared to 30 the prior year.

The Court of Appeals, which has substantially less discretion over its docket than the Supreme Court, decided 2,400 cases last year, only 100 decisions shy of the 2019-2020 fiscal year. However, the Court of Appeals last year issued substantially fewer published opinions – meaning decisions that set a precedent for the trial courts to follow. There were 180 such opinions issued in 2019-2020, and only 133 last year.

Zoom in on the Supreme Court

At a conference for appellate judges and lawyers earlier this month, attorney Geoffrey C. Klingsporn presented an in-depth look at the Supreme Court’s work, with contributions from data analyst Scott Hanks. Unlike the Judicial Department’s statistical data ending in mid-2022, Klingsporn’s data on the Supreme Court spanned 2022-2023.

Over the last 10 years, the time between a case’s placement on the court’s docket and oral argument has decreased to 409 days on average. Similarly, the time between oral argument and a written decision has dropped precipitously, from 231 days in 2013 to 109 days in 2023.

Boatright has attributed the increased efficiency to conversations between the justices before the majority opinion is written, with the author having a better sense of the individual members’ positions and how to best keep the majority together.

In the current fiscal year, Justice Richard L. Gabriel authored the most opinions – including, by far, the most dissenting opinions. Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr., on the other hand, wrote the highest number of majority opinions. In addition, Justice Monica M. Márquez has written the fewest number of opinions, while Justice Melissa Hart is the only member of the court to have authored strictly majority opinions, with no concurrences or dissents.

According to Klingsporn and Hanks’ analysis, Samour was the justice most frequently in the majority, while Gabriel was the biggest dissenter.

Diversity

In 2019, the legislature approved a position in the judicial branch to coordinate outreach for judge vacancies. That person, Sumi Lee, releases an annual report about the demographics of the state’s bench.

As of June 30, the percentage of Black judges was proportional to their representation in Colorado’s general population, and a huge increase from 2018 when there was only one Black district court judge statewide. Women are also approaching parity, with 141 female judges out of roughly 340 in total.

Where Colorado’s judiciary is falling short, relative to the population as a whole, is in the number of Asian, American Indian and – most acutely – Hispanic judges. By the end of the fiscal year, there were only 32 sitting Hispanic judges, largely concentrated in the Denver metro area.

“Even though the need for Hispanic/Latino judges is significant, Hispanic/Latino judges are the only race/ethnicity that is currently represented on all levels of the Colorado state courts,” Lee wrote.

Her report also contained a warning to the legal profession: 32% of active attorneys live in Denver, compared to only 12% of the state’s population that resides in Denver. Lee cautioned that diversifying the bench in rural areas will become more difficult if few lawyers are applying to judgeships.

Retention and discipline

All judges who appeared on the 2022 ballot received favorable recommendations from their citizen-led performance commissions. However, voters in La Plata County narrowly declined to give a full term to newly-appointed County Court Judge Anne K. Woods. Colorado Politics reported that a combination of Woods’ own missteps, a perception she was too lenient to the criminally accused, and unusual public opposition from the local Republican Party contributed to her loss.

One person, former Summit County District Court Judge Mark D. Thompson, received a public censure in 2022 for allegedly menacing his stepson with an assault rifle. The Colorado Commission on Judicial Discipline also took three other corrective actions against judges. While the number of cases involving serious misconduct rose last year, there were fewer private and public admonishments given to judges than in years past.

Federal caseloads

As of Dec. 31, case filings in Colorado’s federal trial court were lower than in each of the five preceding years, with 3,904 new cases in 2022 compared to a high of 4,441 cases in 2019.

At the same time, there were 558 cases filed per judge, with the vast majority of those being civil. That number was higher than in neighboring states, with Kansas’ U.S. District Court experiencing 302 cases per judge, Utah’s having 445, and Oklahoma’s three district courts averaging roughly 400 cases per judge.

There were only 17 trials in Colorado, a number that is on par with previous years. Civil cases lasted on average 8.6 months from the time of filing until a resolution, which could mean a trial, settlement or dismissal.

In the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, there were 1,647 appeals filed, the second-lowest among the 11 multistate circuit courts. Compared with 2021, the number was a 3.7% increase. Since 2017, however, the number of appeals has declined 11.5% in the 10th Circuit.

Nationwide, appeals in 2022 were down 6% in the circuit courts compared to the prior year, while trial court filings decreased by 18%, according to the federal judiciary’s annual report.

Pro bono numbers

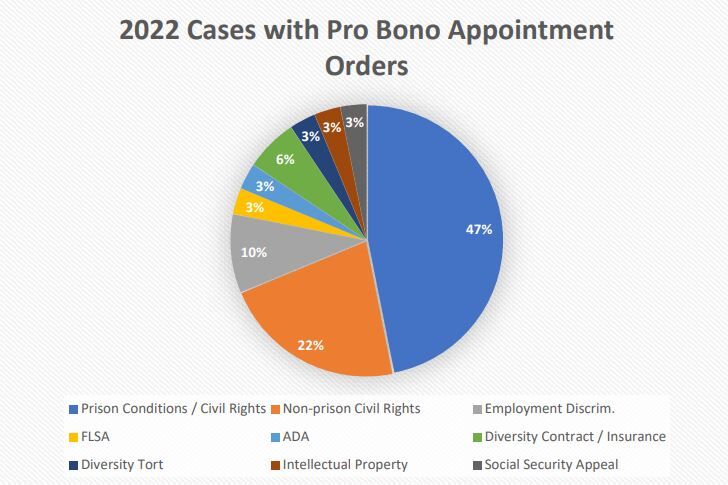

The U.S. District Court launched a pilot program in 2013 to provide self-represented litigants access to “pro bono” counsel from lawyers who volunteer their time. Now, trial judges routinely issue orders allowing for pro bono attorneys to take on civil cases. Last calendar year, there were 32 such orders, resulting in lawyers being placed with 18 clients.

Judges consider the complexity of a case, the merits of the claims and the “interests of justice” in deciding whether to allow a pro bono attorney to represent a party. Nearly half of the appointment orders involved civil and constitutional rights claims from prisoners, with the next-largest category constituting other civil rights actions.

By the end of the year, three of the pro bono cases had settled and six resulted in a jury trial, while litigants in 14 cases remained unrepresented.

In the district court’s annual report, lawyers acknowledged the cases can provide trial experience for attorneys whose civil matters typically settle before reaching a jury. They also advised that communicating with self-represented litigants and setting expectations are important.

“The client had a strong will, and equally strong conviction in the righteousness of his case,” wrote Alan Schindler and Josh Bugos, who represented a man suing Denver sheriff’s personnel for excessive force. “At the same time, his injuries were not obvious – no broken bones or surgeries needed – making it difficult to prove damages at a seven-figure value, which was the client’s original perception of the case.”

The plaintiff ultimately reached a five-figure settlement with the city.

Personnel changes

President Joe Biden took office in 2021 with one existing vacancy on Colorado’s federal trial court, and the turnover only accelerated from there.

Last year, Biden appointed two new trial judges, Charlotte N. Sweeney and Nina Y. Wang, and nominated a third, Gordon P. Gallagher (who took office this year). The U.S. District Court also announced that it hired two new magistrate judges, one of whom has already taken her seat and the other will be sworn in later this year.

The only persistent vacancy remaining at the federal level is on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, which has jurisdiction over appeals arising from Colorado and five neighboring states. A seat based in Kansas has been vacant for more than two years. There is no nominee.