Colorado appeals court reverses conviction for spitting on officer in light of Supreme Court decision

Following the Colorado Supreme Court’s recent decision clarifying when it is a felony offense to spit on police officers, the state’s Court of Appeals last week agreed a man’s Pitkin County conviction for his own act of spitting could not stand.

The legislature in 2015 split the offense of spitting on a first responder into two categories: a felony if there is an intent to “infect, injure, or harm” and a misdemeanor if the intent is to “harass, annoy, threaten, or alarm.” A jury, confused about the meaning of “harm,” convicted Aichardo Mandez-Ramirez in 2019 of a felony, after the trial judge declined to elaborate on what constituted harm.

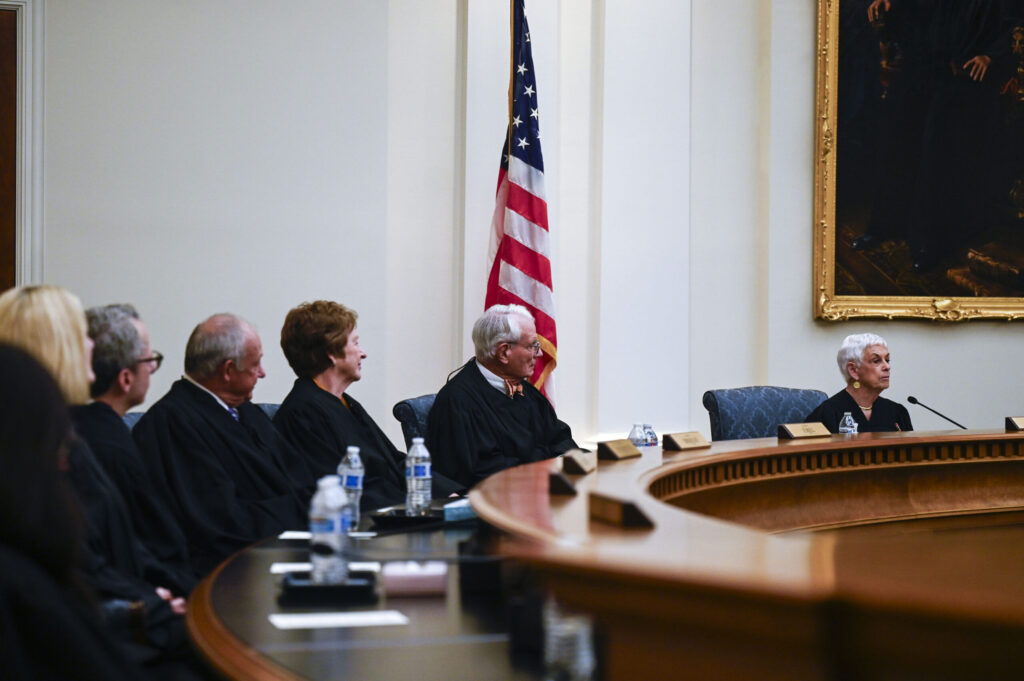

Given the possibility that Mandez-Ramirez’s jury convicted him based on a faulty understanding of the term, a three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals reversed his conviction. Although the prosecution originally argued against a new trial, the Colorado Attorney General’s Office later conceded a reversal was necessary given the Supreme Court’s newly-issued guidance.

In September, the justices handed down a decision in Plemmons v. People, in which a defendant was convicted of assaulting a peace officer as a felony after she spat on a pair of sheriff’s deputies. The Supreme Court agreed the word “harm” was ambiguous, and jurors could have speculated about what it meant without a proper definition.

“We conclude that it is a defendant’s intent to cause prolonged damage – whether physical, psychological, emotional, or some combination of all three – rather than temporary shock or minor discomfort that elevates identical conduct from a misdemeanor to a felony in this context,” wrote Justice William W. Hood III for the court, while a minority of his colleagues suggested the cutoff should be physical harm only.

In Mandez-Ramirez’s case, he swore at a passing Basalt police sergeant, prompting the sergeant to contact dispatch. After learning that there was a “reason to detain” Mandez-Ramirez, the sergeant remained with Mandez-Ramirez until backup arrived. The two officers then grabbed Mandez-Ramirez and tried to handcuff him, while Mandez-Ramirez resisted.

Once the officers put Mandez-Ramirez in a patrol car, he screamed a sexist slur and spat at one of the officers. The spit landed on her shirt. The officer later testified there “wasn’t that much spit, honestly.” Dispatchers then informed the officers that Mandez-Ramirez was not actually wanted after all.

Still, prosecutors charged him with resisting arrest, a misdemeanor, and felony assault for spitting. Jurors convicted him after deliberating for six hours.

The jury indicated, however, that it was having trouble applying the law against spitting. It sent District Court Judge Christopher Seldin a note asking about the definition of “intent to harm.” After consulting with the parties, Seldin declined to provide a definition. The jury sent him another note asking whether spitting as an “insult” or as “disrespect,” without a physical injury, counted as harm.

Seldin again replied with no definition, but told jurors to “apply your understanding gained from your life experiences.”

When Mandez-Ramirez’s case reached the Court of Appeals, his attorney argued the Plemmons decision required a new trial using the Supreme Court’s clarification that harm requires an intent for “prolonged damage.”

“Especially considered in light of the jury’s question asking whether ‘disrespect’ and ‘insult(s)’ were sufficient to establish the required harm,” agreed Judge Stephanie Dunn in the court’s March 23 opinion, “we are not confident that the jury held the prosecution to its burden to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Mandez-Ramirez intended to cause” such damage.

The appellate panel ordered a new trial solely for Mandez-Ramirez’s assault conviction. It upheld his second conviction for resisting arrest, even though the panel was concerned about comments the prosecutor made during closing argument. He told jurors that “in a lot of other jurisdictions” there were “places he would have ended up with a lot more than a scrape on his knee.”

Mandez-Ramirez contended the prosecutor was using a “dog whistle” to imply that Mandez-Ramirez, who is a person of color, should consider himself “lucky” for not being seriously or fatally injured. Dunn, in the panel’s opinion, did not endorse that argument, but she agreed the prosecutor was on thin ice.

“Indeed, even the veiled reference to police violence in other places potentially injected racial considerations into the trial,” she warned.

The case is People v. Mandez-Ramirez.