Appeals court clarifies boundaries of restitution orders, return of seized property

After two criminal defendants with convictions more than a decade old filed challenges implicating a pair of recent Colorado Supreme Court rulings, the state’s Court of Appeals has now filled in the gaps on the process for ordering restitution to victims and for reclaiming property seized by law enforcement.

Two separate appellate panels took the Supreme Court’s recent directives and attempted to apply them to circumstances not raised explicitly in the high court’s decisions. In each instance, the panels sided against the defendants.

In the first case out of El Paso County, Audrey Lee Tennyson pleaded guilty in 2008 to aggravated robbery. He received a sentence of 26 years in prison and agreed to pay restitution to his victims.

Under Colorado law, most convictions require judges to consider whether a defendant should pay monetary restitution. At the time of Tennyson’s conviction, the law gave prosecutors 90 days (now 91) after sentencing to request a specific amount, and trial judges likewise had 90 days to impose the restitution amount. The law also enables judges to extend either deadline.

At sentencing, the judge presiding over Tennyson’s case agreed to restitution, but the prosecutor asked to “reserve” the determination of the amount. Ultimately, the judge imposed restitution in excess of $12,000 far beyond the 90-day deadline.

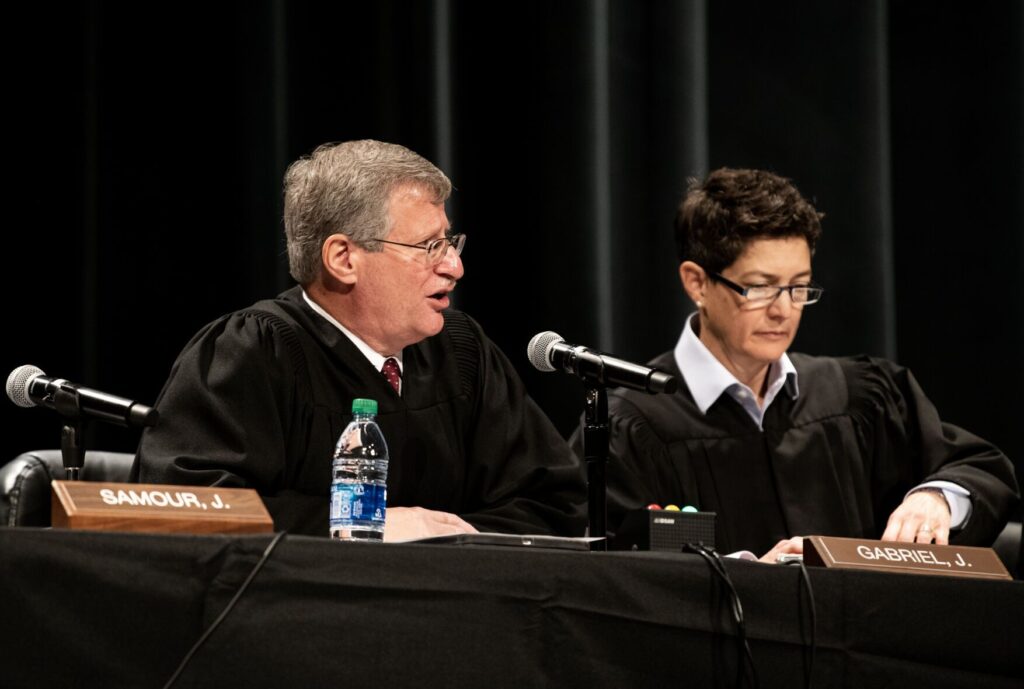

In November 2021, the Supreme Court issued a decision to clarify the process for ordering restitution. The “longstanding practice” used by prosecutors and trial courts did not follow the law, observed Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr., who authored the ruling in People v. Weeks.

Typically, prosecutors were asking trial judges to postpone restitution decisions for 91 days, with judges ordering a specific amount sometime after the prosecution provided a number and the defendant had a chance to object. In reality, the Supreme Court pointed out, prosecutors need to ask for restitution by the sentencing hearing, and the judge needs to make a decision at that time about whether there will be restitution. Afterward, the 91-day deadline applies for determining the specific amount, unless a judge finds “good cause” to extend it.

Tennyson argued on appeal that his restitution order, imposed beyond the then-90-day window, amounted to an illegal sentence.

“In this case, the trial court lacked authority to order restitution beyond the 90-day deadline,” wrote public defender Andrea R. Gammell. “Therefore, Tennyson’s sentence was not authorized by law because it failed to comply with the statutory restitution requirement.”

The prosecution, however, believed Tennyson’s challenge did not implicate an illegal sentence, but a sentence allegedly imposed in an “illegal manner,” which must be challenged within 120 days. The difference, according to Assistant Attorney General Frank R. Lawson, was that the trial judge had the authority to order Tennyson to pay restitution as part of his sentence. That the order came too late was simply a “procedural” deviation.

“Challenges that fall within this latter category do not go to the legality of the sentence, but to the legality of the manner in which it was imposed,” Lawson argued.

A three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals acknowledged the Supreme Court’s decision in Weeks did not address Tennyson’s circumstances. In Weeks, the trial judge did not initially determine whether there would be restitution at the time of sentencing, whereas for Tennyson, the judge had. The amount of restitution was the only thing left open.

“Based on our analysis,” wrote Judge Sueanna P. Johnson in the Jan. 12 opinion, “a challenge to the timing of the court fixing the amount of restitution is an illegal manner claim. And because Tennyson’s postconviction challenge is to the order determining the amount of restitution, it is time barred.”

She added that a “procedural deficiency” in imposing a specific restitution amount would not nullify a trial judge’s decision that a defendant is responsible for restitution in the first place.

The case is People v. Tennyson.

The second case, out of Park County, implicated a Supreme Court decision from December governing the ability of criminal defendants to seek return of property that police have seized in connection with their investigation.

Prior to the justices’ decision in Woo v. El Paso County Sheriff’s Office, the Court of Appeals was split over whether a trial judge presiding over a defendant’s criminal case retains the ability to order the return of personal property after sentencing. The Supreme Court clarified that trial judges do have authority to hear such requests whenever they have jurisdiction over the underlying criminal case – meaning, broadly, anytime the case is not pending before an appellate court.

Law enforcement seized several items from Craig S. Robledo in 2008, including a cell phone, MP3 player and portable speaker. Robledo estimated they were worth $700. He subsequently pleaded guilty in 2009 to attempted witness tampering and violating a protection order.

Soon after, Robledo requested the return of his possessions and a judge directed law enforcement to give the items to Robledo’s mother if they were not relevant to the criminal case. But Robledo continued to ask for his property, filing another motion in 2014 and a third motion in 2021.

In February 2021, then-District Court Judge Stephen A. Groome denied the motion with one sentence: “Too much time has elapsed to consider request.”

Robledo then appealed, but while the case was pending, the Supreme Court decided Woo. Unlike Robledo’s situation, Woo involved a motion filed shortly after the defendant’s conviction. Therefore, the Supreme Court did not address whether some requests for property could be too late to act upon.

The appellate panel reviewing Robledo’s case declined to recognize a firm deadline, but acknowledged the interest in resolving defendants’ requests for property “wanes over time.”

“Without deciding where the outer boundaries of timeliness might lie, we have no trouble agreeing with the district court that, under the circumstances of this case, twelve years lies on the ‘unreasonably untimely’ side of that line,” wrote Judge Karl L. Schock in the panel’s Dec. 29 opinion.

The panel also relied on two other reasons for turning away the appeal: Robledo had already raised the issue in previous motions and he had agreed to forfeit any seized items in his plea deal. The panel’s decision was designated as unpublished, meaning it is not meant to set a precedent.

The case is People v. Robledo-Valdez.