Appeals court finds no constitutional violation after judge told public to leave courtroom

Colorado’s second-highest court ruled on Thursday that an Arapahoe County judge did not violate the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a public trial when he ordered the one observer to a criminal proceeding out of his courtroom during jury selection.

A three-judge panel for the Court of Appeals emphasized its findings in the case of Terance Jamal Black hinged on the unique set of circumstances, in which a small courtroom combined with a large jury pool led the trial judge to believe he had no spare seats for the public.

“We agree with Mr. Black that, by telling the only member of the public who was present at the start of voir dire to leave (albeit temporarily), the district court completely closed the courtroom to the public,” wrote Judge David H. Yun in the panel’s Nov. 3 opinion. However, “the closure was so trivial that it did not implicate Mr. Black’s public trial right.”

The appellate court’s decision came within days of a Colorado Supreme Court ruling on the constitutional guarantee of a public trial. In the cases of People v. Turner and People v. Cruse, which also arose from Arapahoe County, the court acknowledged a judge’s decision to exclude the wife of one of the defendants from three-and-a-half days of the trial triggered the Sixth Amendment’s protections. However, by 6-1, the justices ultimately concluded the exclusion was justified.

The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized the right to a public trial serves multiple purposes in the criminal justice system, including by ensuring the defendant receives a fair trial and by discouraging perjury. At the same time, the right must sometimes give way when it conflicts with other concerns or constitutional protections.

Consequently, the 1984 decision of Waller v. Georgia laid out the factors trial judges must consider when deciding whether to close their courtroom to some or all members of the public. Those “Waller factors” include the narrowness of the courtroom closure, the “overriding interest” behind excluding certain persons and the availability of alternatives that would not require the public to leave.

However, two years ago, the Colorado Supreme Court opted to allow some courtroom closures to be classified as “trivial,” even though that designation does not appear in the Waller ruling itself. In a divided 4-3 decision, the state’s justices found that some courtroom closures are so short or uneventful that they do not implicate the underlying goal of the public trial guarantee, which is to ensure a fair process.

Therefore, trivial closures do not violate the Sixth Amendment, the majority concluded.

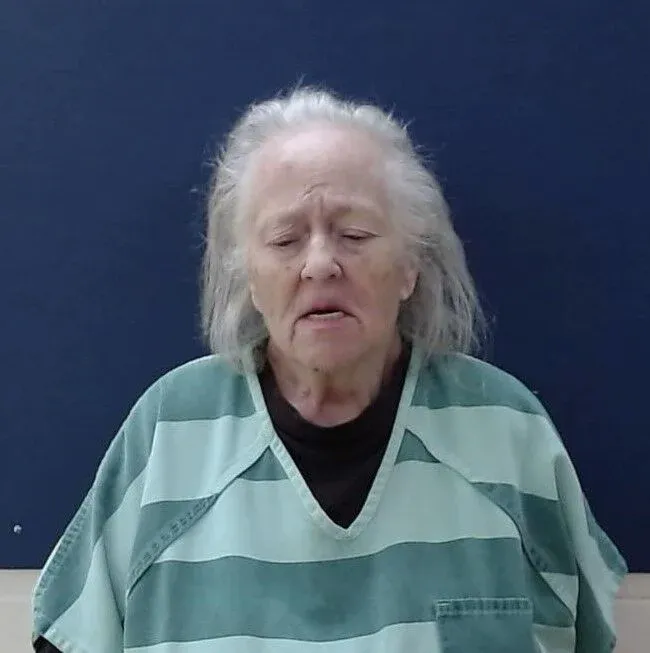

Black stood trial in early 2019 – alongside his mother, Tina Black – for murdering a witness who informed police about the pair’s robbery of an Aurora marijuana dispensary.

Before voir dire, which is the part of jury selection when the parties question prospective jurors, District Court Judge Ryan J. Stuart noticed there was one observer in the courtroom, who apparently knew the defendants. The courtroom only had seats for 50 people, and Stuart told the observer he needed to relinquish his seat for the jury pool. He added that the man could re-enter once there was an available seat.

The attorney for Tina Black objected to the courtroom closure, but Stuart insisted that “we just need all the seats in the courtroom.” When the defense suggested pulling in an extra chair for the observer, Stuart replied that “if there were no concerns with fire safety, we could probably pack the courtroom with a few more seats.”

There was no indication on appeal whether the observer ever re-entered the courtroom. The jury convicted Terance Black of murder and conspiracy to commit murder, and he received a sentence of life in prison.

On appeal, Black argued the trial judge had neglected to analyze the Waller factors before closing his courtroom. He contended there was a practical alternative to asking the one observer to leave – adding another chair for him.

“(H)ere, the court failed to make the slightest accommodation for the only member of the public,” wrote attorney Keyonyu X O’Connell on behalf of Black.

On the other side, the prosecution questioned whether a courtroom closure had even taken place. But even if it had, the attorney general’s office believed the closure fell into the category of trivial.

“Trial courts cannot be required to hold jury trials in sports arenas, and at times real space restrictions will restrict the number of persons in a courtroom at a given time,” wrote Senior Assistant Attorney General Erin K. Grundy.

The Court of Appeals panel did not dispute Stuart’s actions amounted to a courtroom closure. Instead, it found the closure was trivial and did not implicate Black’s Sixth Amendment rights. Therefore, there was no need for the judge to analyze alternatives under the Waller factors.

Yun noted the closure lasted only as long as it took to dismiss the first juror, and Stuart’s explanation at the time indicated he thought the closure was the narrowest option possible. Further, the 50 people in the jury pool were present to ensure the judge and prosecution treated the defendants fairly, which is at the core of the public trial right.

“By so concluding, however, we do not mean to suggest that closing the courtroom during jury selection can never violate that right or that it is necessarily trivial,” Yun cautioned.

The appellate court also rejected Black’s other arguments, including that Arapahoe County was not the correct jurisdiction to prosecute and try him. Black contended that because the murder of David Henderson occurred in Denver, his trial should have taken place there.

The Court of Appeals recognized state law provides flexibility on where prosecutors may try defendants. District attorneys have the option of trying a person in the county where the offense happened or in any county where “an act in furtherance of the offense” occurred.

Testimony established that Terance Black, Tina Black and a third party drove along both sides of East Colfax Ave., which is the dividing line between Adams and Arapahoe counties, while discussing Henderson’s future killing.

Accordingly, the panel ruled it was proper for Black to stand trial in Arapahoe County because the car ride was an act in furtherance of Henderson’s murder.

The case is People v. Black.