Aurora council consider building new campus to curb homelessness

At a price tag of at least $50 million, some Aurora City councilmembers proposed to construct a new campus for the homeless that would offer not only a place to live but also services to aid their transition to self sufficiency.

The vision emerged out of city officials’ travel to two cities in Texas and to Colorado Springs, where they researched strategies to reduce homelessness.

While some councilmembers appear to support the overall concept, the high price tag and undetermined operational expenses appear to be deal breakers to others.

Fireworks erupt as Aurora council debates tax cut

The campaign to curb homelessness also appears to sharpen the ideological divide among Aurora’s leaders, although both sides say they’re committed to finding a solution to a crisis that gnawed its way into city hall. Indeed, the councilmembers’ dueling ideological views on homelessness were on full display during a study session on Monday.

The mayor’s proposal

What’s apparent is the out-of-town visits have made a huge impression on the councilmembers, whose arguments are shaping the contours of Aurora’s next homelessness policy.

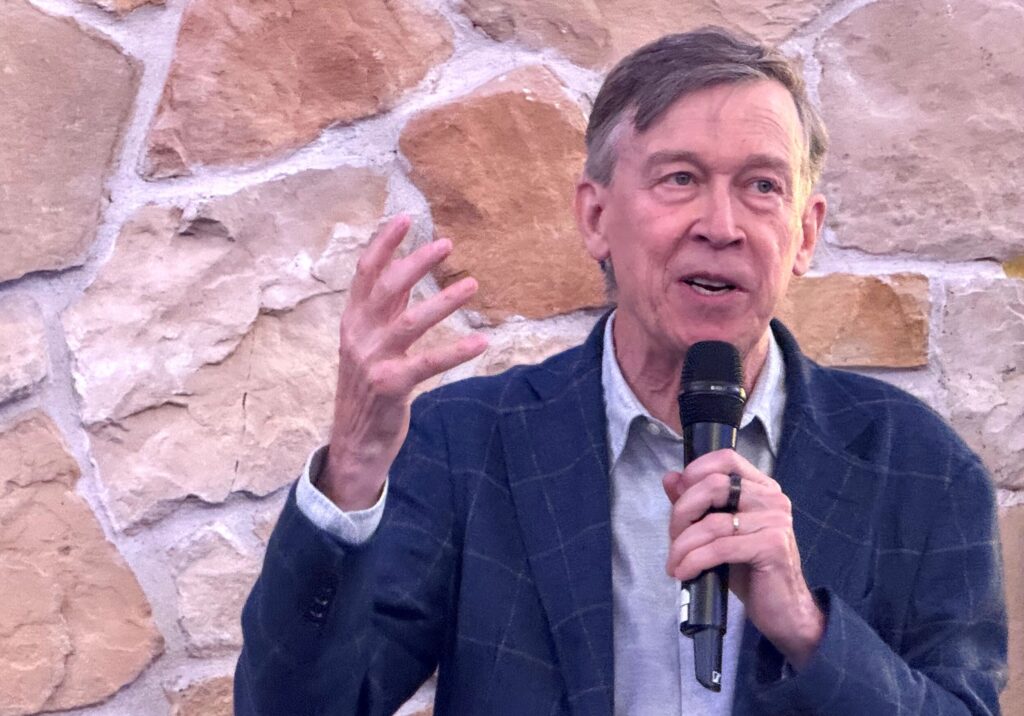

Mayor Mike Coffman is sponsoring a resolution – expected to come before council for formal consideration Monday – that would direct the city manager to begin creating a new comprehensive system for reducing homelessness in Aurora. Coffman said his plan includes the one-stop-shop facility that brings housing programs and services under one roof.

Councilmembers have visited Houston, San Antonio and Colorado Springs in recent weeks to tour “housing first” programs – which provide people with permanent housing, along with individualized social services – and alternatives, such as “treatment first” or “work first” models. These programs typically require some people to access treatment or be working – or at least to keep trying to find a job or receive job skills training – in order to receive housing beyond emergency shelter.

Coffman’s resolution draws inspiration from campuses in all three cities. And while he promotes the “work first” philosophy, it does not mean the city would require people to find work before receiving services, he said.

The tiered system he envisions provides emergency services to everyone without conditions – except substance use would not be permitted on campus.

“That’s just a moral obligation to help people that are in crisis,” he said.

Aurora council to discuss homelessness, redistricting at Monday study session

A second tier offers better living conditions to people who work with case managers and participate in programs, such as mental health or addiction treatment.

The third tier offers transitional housing to people who participate in programs, work and are “on the road to self-sufficiency,” he said.

“My goal is to say, ‘Look, we are going to provide services for everybody in need, but we are going to focus our resources on those who want to affirmatively change their behavior,'” Coffman said.

He said he wants to include “key partners,” such as mental and physical health care providers, job training and placement services, operating from the same site.

Neither Coffman nor Councilmember Dustin Zvonek, who has advocated for similar approaches outlined in Coffman’s resolution, want homeless families or children to be located next to people receiving emergency shelter.

Zvonek foresees providing families with supportive housing in a different location by partnering with area nonprofits, he said.

Coffman does not want the campus to include permanent supportive housing, which he said could duplicate the work of other agencies.

The Aurora Housing Authority plans to build an apartment building for permanent supportive housing, which is also offered by Aurora Mental Health, Coffman noted. The city is also preparing to work with the state as it turns the former Ridge View Youth Services Center near Aurora into a facility for the homeless.

Meanwhile, Mayor Pro Tem Francoise Bergan told The Denver Gazette she will support a campus “if we do it the right way.” To her, that means a navigation center that brings together partners, which provide services, such as mental health treatment and detox. Eventually, the campus could include transitional housing “with certain conditions and job training or work requirement,” she said.

“I also need assurance that it would be operated by a nonprofit who will seek private funding, grants and has a lower dependence on city taxpayer funding,” she said in an email. “I’d like to know if the counties are going to contribute financially as they are responsible for health and human resources.”

Aurora, Colorado officials hunker down in search of a viable homeless strategy

Councilmember Curtis Gardner favors working with regional partners, such as the county and the state, to forge a campus, he said. Reached by email, Gardner said that while the county runs human services, “Aurora certainly can and should be a leader in working to address homelessness in our community.”

Meanwhile, Councilmember Steve Sundberg is still processing everything councilmembers learned in San Antonio, he said by email. He thinks forming the right plan could take several weeks.

Sundberg spoke about cities in the U.S. that he believes have been overly permissive with drug use as setting “the example of what not to do.” Some homeless people in Aurora are not interested in the shelter and resources the city provides as of today, he said, adding he hopes future partnerships change that.

“I do believe a campus will likely be needed,” he said.

A potential site

The council is eying an undeveloped property near Chambers and 32nd Avenue, not far from the Aurora animal shelter, as a potential site for a 5 to 7-acre campus.

“There is a bus route to that area. It is in an industrial area, industrial sort of warehouse area,” Coffman said, adding it is close to I-70 and not near schools or neighborhoods. “I think it’s a good location. I certainly support it.”

While operational costs are unclear until there is a final plan, staff project the cost to build a campus is between $50 million and $70 million, a spokesman said. Operating costs would crystalize once a request for proposals is sent out to groups, notably nonprofit organizations interested in running the campus.

Mayor Pro Tem Bergan has pushed for a nonprofit to run the new program, rather than the city, similar to how the cities councilmembers toured run their models.

That nonprofit and other partner organizations would lead the way on raising the necessary funds to run the system, Zvonek and Coffman said, adding the Colorado Springs Rescue Mission has done that successfully.

Aurora would likely pursue city, county and state pandemic recovery funds and private funding to build the campus. Zvonek and Bergan have pushed for the city’s new system to rely primarily on private and philanthropic dollars, rather than government funding.

“We should not put the burden on the back of our taxpayers,” Bergan said during council’s Monday study session.

For that reason, they don’t foresee conflicts of interest arising if the system largely relies on private funds. The city would be contracting, not paying, a nonprofit to lead the system, Coffman said.

Coffman also believes enough donors would chip in to sustain the model he proposes.

“I think there’s a lot of foundations that are interested,” he said.

If council approves his resolution, the city’s next step is to delve into design work and apply for grants to fund construction, Coffman said. If the city is not successful at getting a state grant, “then it’s going to be a more scaled back version” of the same concept, Coffman said.

‘An exceptionally expensive endeavor’

Some councilmembers are wary of Aurora going it alone, not to mention the fiscal burden the city would have to bear.

Councilmember Juan Marcano said a campus is “an exceptionally expensive endeavor.”

Co-locating services that provide emergency support and case management are all best practices and have his support, he said, adding he does not want Aurora to require that people abide by certain conditions before receiving help. Officials at San Antonio’s Haven for Hope had told Aurora councilmembers during their visit that conditional services are a barrier that results in serving fewer people.

“If you all have your heart set on a campus, again I’m just going to go on record and say I think that’s a terrible idea, just from a cost and logistical standpoint,” said Marcano, who insisted that building and operating a campus is “setting our city up for mid-to-long-term failure.”

The councilmember reiterated his belief that regional collaboration among Denver metro area communities is needed to solve the homeless issue. Marcano is hopeful Aurora would lead the way toward a regional approach.

Additionally, he maintains that embracing Houston’s “housing first” approach is best for Aurora. In Houston, people might receive emergency shelter, but largely are supported by tools such as vouchers, case management and services tailored to an individual’s needs. Houston’s “housing first” model’s success rates are far better than San Antonio’s campus, he said.

The debate on homelessness often sharply illustrates policymakers’ conservative tendency – which says homelessness is the result of abdication of personal responsibility, and the cure, therefore, is not absolution without atonement – and their progressive instincts, which argues that the individual’s fall is often the result of systemic inequities, and the government, with its vast resources, should offer a corrective action.

Glimpses of that divide were visible on Monday.

While Marcano believes that the nation’s socioeconomic system produces homelessness, Zvonek attributes the malady to lenient drug laws and inaccessible mental health treatment.

The nation’s socioeconomic system has been the most successful in history, Zvonek said.

Marcano said he’s isn’t buying the argument.

“There are folks who are housed that have substance abuse issues. They manage to keep their housing because they have the means to,” Marcano said. “There are people, more people on the street who develop substance abuse issues as a way to cope with their horrible conditions and the trauma that they have experienced as a result of becoming homeless. And then we compound on them through strategies like camping bans.”

What both sides agree is that the realities on the ground are grim. Aurora did not complete a 2021 homeless count because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but last year there were nearly 600 sheltered people in the city. Aurora has between 130 and 150 shelter beds available each night, according to the city. Meanwhile, the number of affordable housing units ranges from 7,500 to 8,500.

Aurora’s experience, in fact, is far from unique. Metro Denver is struggling to address homelessness, which jumped by 12.8% – from 6,104 to 6,888 – between January 2020 and January this year, and cities like Aurora struggle to keep up.

Marcano, for example, told The Denver Gazette he is aware of 110 units of permanent supportive housing in Aurora, with nearly half of those dedicated to veterans and their immediate family. Aurora Mental Health is bringing roughly 40 units to the city in the next couple of years.

That’s not nearly adequate, he said.

“We’re far behind as a city and as a region, as evidenced by the growing homeless population,” he said in an email.

When Marcano pressed Coffman on Monday about why he prefers a campus, the mayor said it is “the most effective” approach. Coffman said he does not believe Houston’s model is sustainable because the city has relied often on one-time dollars, such as pandemic relief funds, to fund its programs. The “housing first” model is also expensive, he said.

“I mean it’s $100 million a year, $10 million from the private sector,” he said of Houston’s system.