Advocates for kids with disabilities say bill regulating rideshare companies lacks safety provisions

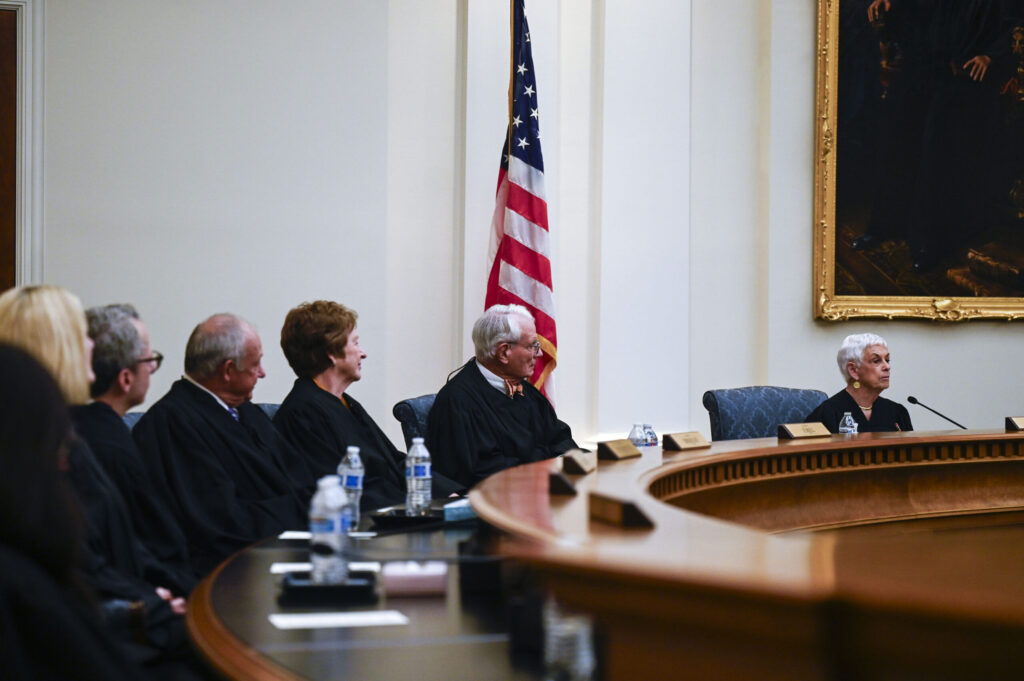

Update: the House State, Civic, Military & Veterans Affairs Committee on Thursday voted 7-2 to approve SB 144, with amendments. The bill now goes to the full House.

Should rideshare companies be able to transport schoolchildren?

Two such entities already provide the service in Colorado, but a 2021 decision by a regulatory agency threw a monkey wrench into which government body has oversight over the companies, raising questions about accountability and safety.

Now legislators are trying to untangle that convoluted regulatory framework they say is inhibiting government entities, notably schools, from fully taking advantage of services at a time of acute transportation needs.

At issue is a Senate bill that seeks to untangle what proponents describe as a bureaucratic web around ridesharing companies’ ability to provide transportation to schoolchildren.

Senate Bill 144 makes two major changes to the statutes: First, it expressly allows rideshare companies to contract with a school or any other political subdivision of the state and puts them under a regulatory framework that applies to similar transportation companies. Second, the bill requires contracts to include safety provisions for transporting students.

Supporters argue that the bill is sorely needed to give schools more options to transport pupils.

But advocates for kids with disabilities say they are frustrated with the proposal, arguing it doesn’t go far enough in ensuring the safety of children.

In addition to questions about student safety, the measure also wades into a complex area of cross-agency regulation and competition between companies. Underpinning these issues is Colorado’s efforts to provide a regulatory framework for a relatively newcomer to America’s economy – ridesharing entities – and policymakers’ attempt to tap their services as potential solutions to pressing transportation problems.

Ridesharing entities – technically known as a transportation network company (TNC) – operate under a regulatory regime adopted by the Colorado General Assembly in 2014. Lawmakers then assigned that regulatory task to the Public Utilities Commission. Unlike regular taxis, however, a special set of rules governs TNCs. A recent decision by the Public Utilities Commission noted they are exempt from its “typical regulation of motor carriers and are instead subject to specific TNC requirements that cover the areas of permitting, insurance, operations, vehicle safety inspection, and driver qualifications.”

Here’s the complication: The Public Utilities Commission doesn’t deal with the transportation of minors. That’s the purview of the Colorado Department of Education, which must adhere to strict federal requirements on student transportation. Federal law also dictates that schools must provide transportation for children with disabilities, another area in which the PUC has no experience.

Current state law, in fact, carves out student transportation from PUC authority.

That bifurcated regulatory framework hasn’t stopped some school districts from tapping TNCs to provide transportation services to a certain segment of the student population.

Since 2018, for example, the California-based HopSkipDrive has contracted with human service agencies to provide rides for foster kids and children with disabilities.

A competitor, ALC Schools, which also operates in Colorado, last year questioned whether provisions of the TNC law apply “when a ridesharing company provides transportation of students to and from school, school-related activities, and school-sanctioned activities.”

That question raises safety, notably in the light of the General Assembly’s decision in 2021, through a mammoth bill on transportation, to remove the requirement for TNC drivers to comply with PUC rules requiring proof that a person is medically fit to drive.

Instead, TNC drivers are required to “self-certify” they are physically and mentally fit to drive.

When ALC Schools petitioned the Commission to look into the issue, the Department of Education joined in, seeking clarification over which activities TNCs are permitted to do.

In its filing with the Commission, the education department said it is “at a loss on how to respond to the stream of increasingly pressing questions it receives from school districts” about TNCs that provide student transportation under contracts with school districts.

HopSkipDrive, in its filing with the PUC, asked that regulation of TNCs stay within the PUC’s purview and not transfer over to CDE. However, the PUC decided on March 16 that the authority to regulate transportation for school students falls under the education department.

As noted earlier, one overarching question over which government agency regulates TNCs raises public safety and accountability concerns.

To put it bluntly, which government agency is responsible for ensuring rideshare companies adhere to rules – and whose rules exactly?

Dana Smith, who speaks for the education department, reiterated that transporting children to and from schools falls squarely within the department’s purview.

The department’s rules for companies that provide those services include specialized training for drivers, particularly in dealing with children with special needs, which can include behavioral issues tied to disabilities. Rules also govern the vehicles used to transport children, Smith said.

The regulations also require drivers, including those who operate private vehicles, to have written documentation showing first aid training, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation and universal precautions, within 90 calendar days after initial employment. They also need to be recertified every two years.

In addition, the rules require training on the proper use and maintenance of Child Safety Restraint Systems and wheelchair securement.

None of that is covered under existing PUC regulations that apply to TNCs, and SB 144, as amended by the Senate, doesn’t direct the PUC to create those rules.

Under SB 144, a TNC’s contract with a school would include specific provisions for safety of student passengers – as determined by the school or school district.

That’s insufficient, according to advocates of students with disabilities.

Joy Ann Ruscha, who represents the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, said she is uncomfortable with the lack of safety provisions in the measure and referred to data saying there have been 3,000 sexual harassment and sexual assault complaints filed against ridesharing drivers nationwide. She also cited a 2021 audit on non-emergency medical transportation that found that people, including adults with disabilities, suffered injuries or were stranded during rideshares, effectively arguing that children face similar risks.

“If we had safety concerns with at-risk adults, we have them with at-risk youth,” she said.

Ruscha wants companies that transport kids to school or to school-based activities to fall under the watch of the education department, but she also argues for stricter language.

Ruscha and others point to PUC regulations, for example, that allows the commissioners to waive the rules on operation or maintenance of school transportation vehicles.

Then there’s the issue of background checks, Ruscha said.

Companies, such as Uber and Lyft, conduct their own background checks and keep their own records, and the PUC does not require them to submit copies.

“We never know if TNCs are compliant with background checks, insurance requirements, or car and medical requirements,” Ruscha said. “There’s a trust issue.”

Ruscha said SB 144 implies that an at-risk child has the same safety protections as an adult getting into an Uber or Lyft.

“That’s a concern. Most parents wouldn’t put their 9-year-old with or without a disability in an Uber,” she said. “Your child has fewer safety protections under this bill than a kid on a school bus. That means fewer safety protections than everyone else, and we’re doing this in the name of kids? I don’t think so.”

In a letter submitted to the Senate committee in March, Todd Krommenhoek, who represents ALC Schools, raised similar concerns and pointed out the PUC has no student or minor-specific regulations.

“As someone who has experienced working environments of companies where the regulatory structure does not specifically recognize student needs, and companies that are detailed in their training requirements for students because of regulatory guidance, I believe allowing companies to operate in the same industry without recognition of student needs leaves Colorado students at risk of incident, accident, or mismanagement,” Krommenhoek wrote.

HopSkipDrive officials said the company provides ride services with safety in mind and it operates with its own safety standards.

Joanna McFarland, HopSkipDrive’s CEO, told Colorado Politics the bill would codify current practices, noting the recent PUC ruling puts TNCs into a regulatory gray area. She noted that the company started operating in Colorado at the request of the state Department of Human Services, which needs a way to get foster kids from their foster placements to school.

HopSkipDrive drivers – referred to by the company as “care-drivers” – must have five years of care-giving experience, which can include being nannies, baby-sitters, nurses, teachers or parents.

“We’re subject to pretty strict regulation because we transport children” and with their own standards of safety, McFarland said.

Its safety standards, however, doesn’t include CPR training – a point critics of the bill raised.

In response, McFarland pointed out that in 20 million miles driven, not once has a driver had to perform CPR in the company’s history.

“I’m in favor of tying safety to data and accountability,” McFarland said.

She argued that school districts need flexibility and rules must be pragmatic. Requiring every driver to be trained on restraints when not every child needs it, for example, could limit the pool of available drivers. She also insisted such requirements don’t necessarily lead to enhanced safety.

McFarland also said company drivers are trained on how to use HopSkipDrive services, such as coaching and mandatory reporting on trauma-informed care, as well as instruction on how to work with students with disabilities and training on behavioral issues.

What’s most important, she said, is that school districts that contract with HopSkipDrive are confident in the company’s abilities.

“Families want quality options, and that’s what we’re offering,” added Trish Donahue, HopSkipDrive’s vice-president for legal and policy.

Sen. Rachel Zenzinger, D-Arvada, the bill’s sponsor, told Colorado Politics one of her primary reasons for the bill is to deal with the issue of transporting foster kids. A child in the foster care system can get uprooted from a foster home multiple times, so it’s important that those children maintain their relationships with their home schools, she said.

A contract between a school and a TNC ensures that child still gets to that school, providing needed stability.

Rep. Cathy Kipp, D-Fort Collins, said she is preparing an amendment to address issues raised by advocates of people with disabilities. That amendment would require drivers to receive training in mandatory reporting, safe driving practices, first aid and CPR. That training also includes education on “special considerations for transporting students with disabilities,” emergency preparedness and safe pick-up and drop-off practices.

The amendment would also require criminal background checks and bars drivers who have been convicted of felonies or misdemeanors on unlawful sexual behavior, particularly involving children. TNCs would be required to notify a school or school district with whom they have a contract about any safety or security incidents involving services provided to students, and that notice would go to any school or school district with whom they have a contract.

Finally, the amendment would require a review and update of the rules after three years, a joint effort by the PUC and education department.

“Ultimately, we need to make sure kids’ safety is the priority,” Kipp said.

PUC decision regarding TNCs in schools