House judiciary panel tackles sweeping legislative response to fentanyl crisis

Editor’s note: The House Judiciary Committee this afternoon heard testimony on a sweeping legislation aimed at confronting Colorado’s fentanyl crisis. This story has been updated multiple times. Here’s the latest.

Herod can’t attend fentanyl hearing as Joint Budget Committee meets at the same time

Rep. Leslie Herod, who was temporarily appointed to the House Judiciary Committee on Tuesday, won’t be attending Wednesday’s second day of the hearing on a sweeping fentanyl bill that aims to confront Colorado’s fentanyl crisis.

“I appreciate the Speaker @AlecGarnett appointing me to serve on Judiciary yesterday. I am disappointed that I can’t be there today, but legislative duties have me elsewhere,” Herod wrote on Twitter.

Herod is attending a Joint Budget Committee meeting that’s occurring at the same time.

Herod also praised the judiciary committee’s decision to hear from the people who signed up to testify last night.

“While we had hoped that amendment process would happen last night, limiting testimony was not an option and to rush through amendments would not have been prudent,” she said. “The Speaker made the right decision to hold amendments until they could be properly drafted and considered with clear heads. I support his leadership and look forward to continuing to work on this important legislation.”

Amendments on fentanyl bill delayed to Wednesday

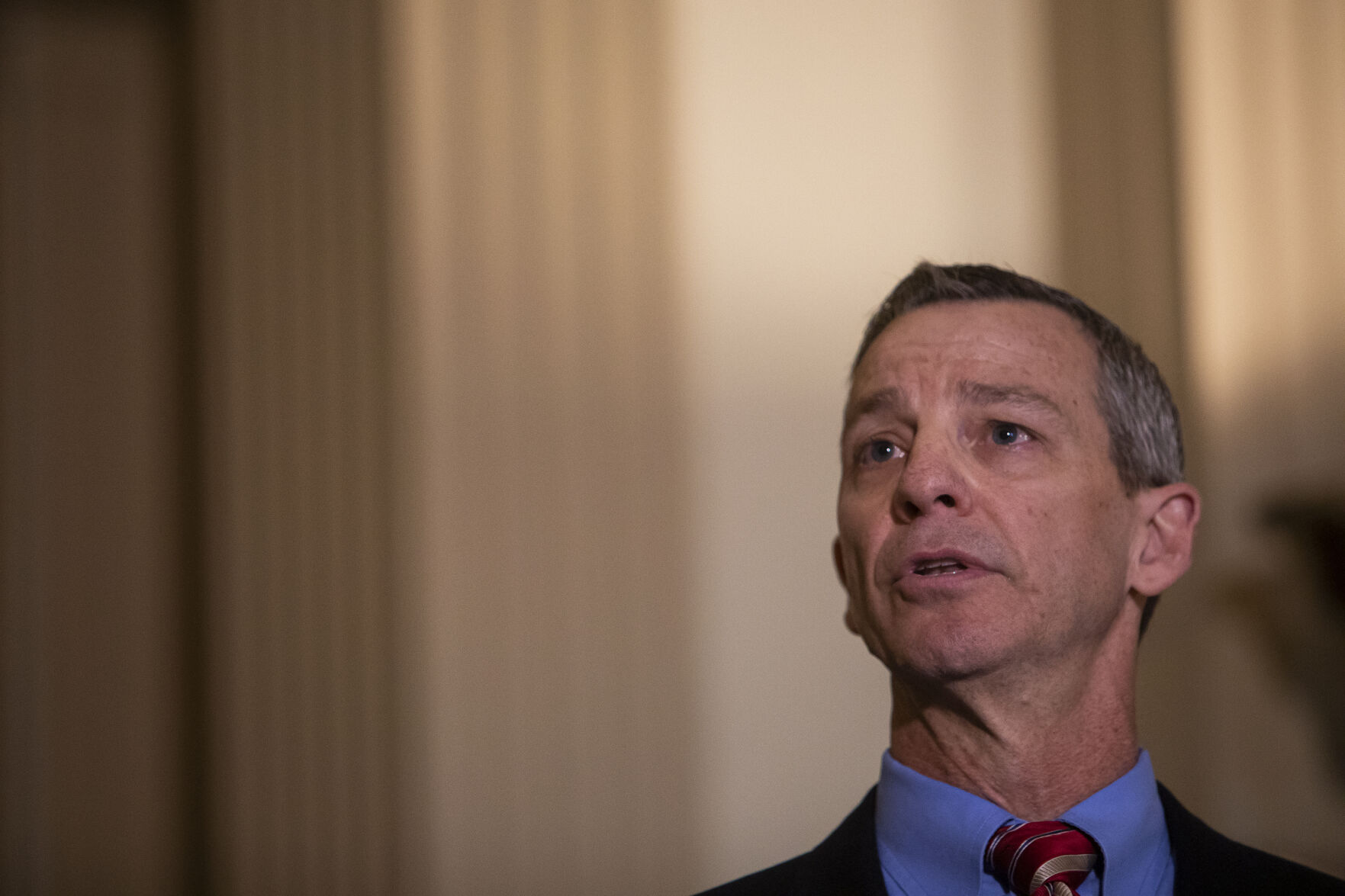

Nearly nine hours after Tuesday’s hearing on the legislature’s sweeping fentanyl bill began and with public testimony continuing, Rep. Mike Weissman, chair of the House Judiciary Committee, said lawmakers would not consider amendments to the bill until Wednesday afternoon.

He committed to allowing everyone who has signed up to testify to do so before the committee adjourns. But, he said, because many have yet to do so, the committee would delay discussing amendments until its meeting at 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday.

Lawmakers are expected to discuss amendments related to changing possession laws to lower the amount of fentanyl that would trigger a felony charge.

Law enforcement officials ask for solutions

In a town of less than 4,000, finding 693 pills with fentanyl is a lot.

That’s what happened in Basalt, according to Police Chief Greg Knott, who told the House Judiciary Committee that kids in his town find “blues” -fake oxycodone – and don’t know there’s fentanyl in them.

Knott was part of a panel of law enforcement officials who spoke about the problems of fentanyl in their communities during Tuesday’s hearing on a sweeping measure aimed at confronting the fentanyl crisis in Colorado.

In response to a question about how to deal with those arrested for felony charges tied to any level of possession of fentanyl, Sheriff Tyler Brown of Arapahoe County said he would love to see expungement of records for those who complete successful treatment.

“We can get there,” Brown told the committee. “That leverage allows us the ability to find a successful treatment plan and then we work to expunge.”

That, he said, creates a pathway for someone to become a productive member of the community again. There’s isn’t a single sheriff who doesn’t want that, Brown added.

Summit County Sheriff Jaime FitzSimons noted what other experts have confirmed – every toxicology screen done in an autopsy in 2021 in his county showed fentanyl.

Denver resident tells legislators he lost six friends to fentanyl

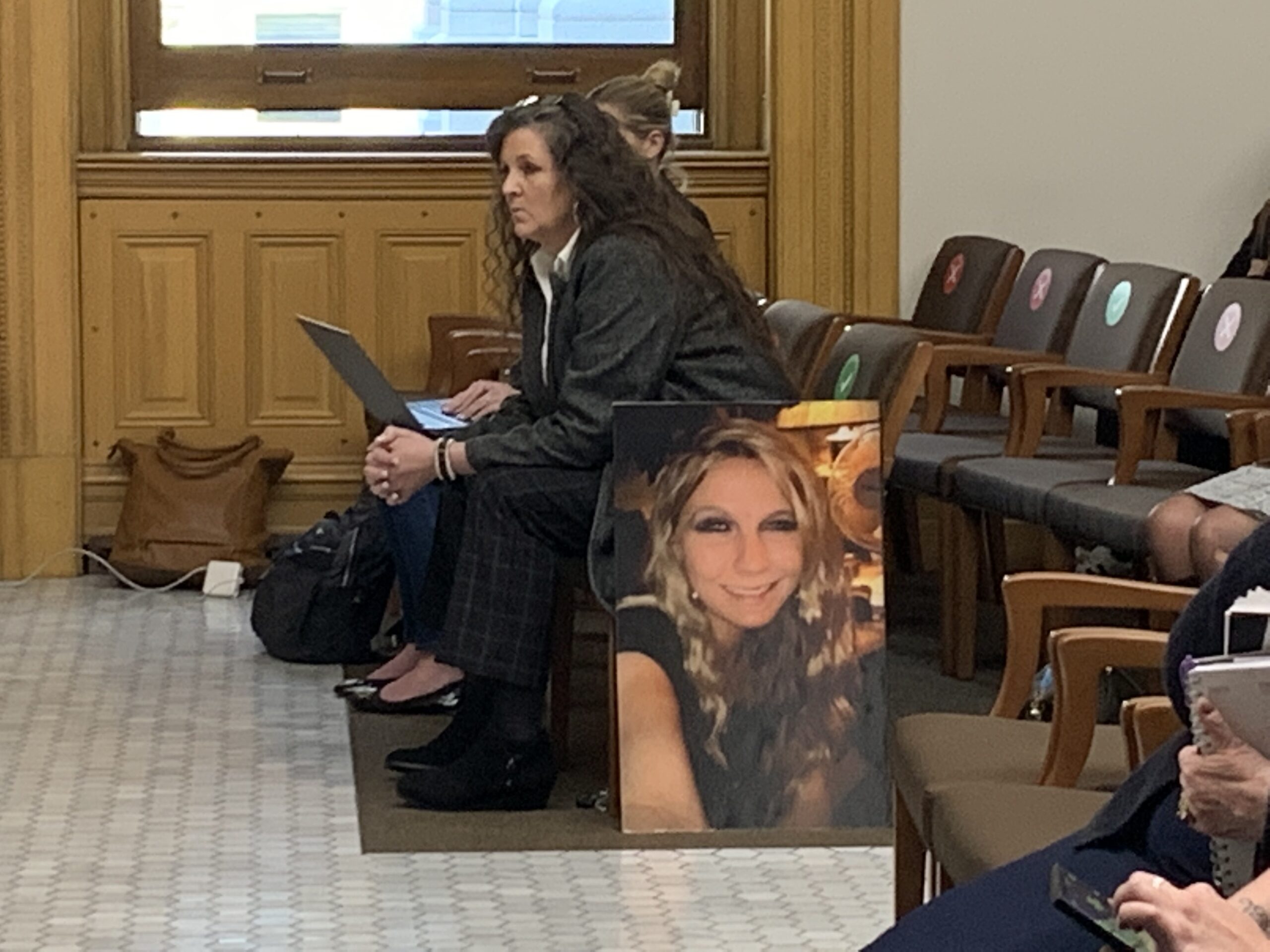

Tesa Alirez-Ruiz, who lost her 18-year-old daughter to fentanyl, said pleas to law enforcement to hold those who provided the drugs to her child accountable went unanswered.

She pleaded with the committee members to put more money into law enforcement for investigations, lamenting those who distribute the drugs get no more than a slap on the wrist.

Alirez-Ruiz was among several parents who fought through tears and testified about losing their children to fentanyl. Others recounted how the drug took away their friends.

“Me and my peers are scared and don’t know what to do or who to turn to,” said Bo Gribbon, a resident of Denver who said he has lost six friends to fentanyl.

He advocated for harsher penalties, particularly for dealers.

Rep. Adrienne Benavidez, D-Commerce City, asked if education about what’s in the drug would make a difference.

Yes, he said, but to be honest, most people know that what they’re taking contains fentanyl.

The committee also heard from family members and friends of the five people who died in Commerce City last February, the worst mass casualty event tied to fentanyl in American history.

“She should still be here to celebrate her son’s 11th birthday,” said a sobbing Feliz Sanchez-Garcia, who spoke of her sister, Karina Rodriquez. The son celebrated his birthday on Monday.

Those who have faced drug problems and experienced the criminal justice system countered the calls for felony charges for low-level possession.

“I’m hearing a lot of revenge and not a lot of logic,” said Thomas Hernandez, who was incarcerated several times for drugs.

“Our kids and adults are using fentanyl, and are not afraid of felonies or even death,” said Hernandez, who now runs Tribe Recovery Homes.

“They have Narcan in their backpacks. They don’t care. When they finally do care, and have a felony,” they won’t be able to get housing, education or a job, he said.

Getting treatment once someone is out of prison is also difficult, they said. That felony can keep people out of treatment programs because the person lacks stable housing.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

Harm reduction experts blast efforts to pass harsher criminal response to crisis

One of Colorado’s leading harm reduction experts lambasted the bill and attempts to increase criminal penalties for anyone in possession of fentanyl. Another advocate said it is “illogical and nonsensical” to suggest a law change in 2019, which made possession of fewer than 4 grams of fentanyl and other substances a misdemeanor, is the cause of the state’s overdose crisis.

Lisa Raville, executive director of Denver’s Harm Reduction Action Center, argued that mandatory treatment and potentially “re-felonizing” any amount of fentanyl doesn’t work.

If it did, she said, “we would’ve gotten this under control a long time ago.”

Raville said policymakers should instead be discussing a safe supply of drugs – meaning state-approved access to pharmaceutical-grade drugs – and safe-use sites, where users can ingest illicit substances under the watchful eyes of providers and experts.

She said many users she works have signed documents indicating they don’t want anyone charged in the event of their overdose. A provision of the bill would create penalties for dealing fentanyl that resulted in someone’s death.

Elisabeth Epps, a state House candidate and founder of the Colorado Freedom Fund, also blasted mandatory treatment. She said if incarcerating people helped them get clean, she’d fully support it. But it doesn’t, she argued.

Asked by Rep. Jennifer Bacon if “felonizing” fentanyl possession has had positive effects elsewhere, Raville said it had not because it doesn’t solve problems in the illicit drug supply.

Rep. Rod Bockenfeld asked Epps if the “War on Drugs” had truly failed, and he said that fentanyl overdoses in Colorado began to jump in 2019, the same year that the legislature de-felonized possession of small quantities of fentanyl.

“Is it possible that maybe the War on Drugs had some check and balance?” he asked.

Epps noted that the law change didn’t go into effect until March 1, 2020, just when the pandemic was starting.

A bipartisan Congressional panel said in a report released in February that the pandemic played a significant role in increasing the fentanyl overdose crisis nationwide, along with the overall increase of fentanyl in the drug supply.

She asked if Bockenfeld thought that drug users, just before they took an illicit substance, stopped and wondered if the drug carried a felony or misdemeanor penalty.

“To pull out one factor and to suggest that by changing this penalty (and say) that’s what leads to overdose deaths, I think that’s illogical and nonsensical and it’s offensive to those of us who’ve been doing this work and surviving,” she said to Bockenfeld. “There’s too much at stake to suggest that’s the work.”

Law enforcement officials press for felony charge

Deputy Chief Adrian Vasquez of the Colorado Springs police department told the committee that any possession of fentanyl should be a felony, that there is no “relatively safe amount of fentanyl” and public policy should demonstrate its seriousness.

John Camper, director of the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, also his agency can only test for whether a drug is positive or negative for fentanyl in response to a question from Herod on when the CBI would determine whether a drug is heroin – or some other illicit drug – and when it is fentanyl for charging purposes. The bureau does not have the capability to tell how much fentanyl is in a drug, Camper said.

Camper added that the Department of Public Safety supports lowering the felony threshold for possession, stating that 4 grams still equates to 40 pills at 0.1 gram of fentanyl per pill.

Attorney General Phil Weiser presses for changes in fentanyl bill

While Attorney General Phil Weiser did not testify in person, he sent the House Judiciary Committee a letter, saying he supports the bill but also presses for changes.

He asked that the legislation devote significant resources to law enforcement to interrupt the supply chain of fentanyl coming into the state. Weiser said he supports an amendment that would make possession of any amount of pure fentanyl a felony, and a lowered threshold for fentanyl possession when it is part of a compound, as is the case with most illicit street drugs.

“This is a necessary change to the criminal code,” Weiser wrote.

District Attorneys support bill, also backs stronger felony charges for possession

District attorneys from three jurisdictions testified that while the bill isn’t perfect, the legislature cannot wait another year to address the problem.

District Attorney Dan Rubinstein of Mesa County said regardless of any amendments that may surface, the committee must pass the measure. He complimented the increase in penalties for distribution and creating a felony for distribution resulting in death.

Michael Dougherty, the district attorney for Boulder County, said there are valid concerns about the bill, but if it fails, people will continue to die at an alarming rate.

George Brauchler, a former district attorney for the 18th Judicial District, called for a felony charge for any level of possession, denying it is an attempt to “felonize” addicts. No one goes to prison for simple possession, he insisted. If lawmakers are concerned with whether jails would fill up with addicts, Brauchler suggested putting a sunset on the bill and review its effects in two years.

“Let’s see if we fill up a single prison bed with one addict,” he said.

Rubinstein added that the purpose of a felony charge is to force people into treatment, arguing a felony level encourages that outcome. Having a felony as an incentive makes a difference in getting addicts to go to treatment, Brauchler added.

Dougherty said he heard a recent presentation from two young women, one of whom said she went to a drug diversion program, committed herself to the program and got sober. It works for some people, he said.

The criminal justice system did not compel the other woman to get the treatment she needed, and she wound up with convictions that makes it difficult to get a job, Dougherty said, adding the criminal justice system is not one-size-fits-all and does not work for everyone.

In response to a question from Rep. Leslie Herod, the district attorneys said they do not see criminal cases applying to pure fentanyl. Rubinstein said pure fentanyl is so potent and deadly in its pure form that it’s completely useless to have around. He also noted that the Colorado Bureau of Investigation is unable to test the purity or level of fentanyl in a pill.

State policymakers identify soaring criminality in Colorado as a key challenge they vow tackle this year. Some blame the state’s “criminal friendly” policies as contributing to the trend, while others say the “lock up everybody” mentality has a longer record of failing communities. Colorado Politics Managing Editor Luige Del Puerto leads a panel of experts to discuss crime in the state, and what can be done about it. Panelists: ? Lisa Pasko, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Sociology and Criminology, Universit (lisa.pasko@du.edu) ? Paul Pazen, Chief, Denver Police Department (Paul.pazen@denvergov.org) ? Mitch Morrissey, Criminal Justice Fellow, Common Sense Institute (mitch.r.morrissey@gmail.com) ? Lisa Raville, Executive Director, Harm Reduction Action Center (lisa.harm.reduction@gmail.com)

Healthcare providers criticize proposed legislative response to fentanyl

Three providers who work directly with people using substances all testified strongly against the bill. They said the bill’s efforts to improve harm reduction programs, such as by increasing fentanyl test strips and Naloxone access, don’t outweigh the damage they argued would come from increasing criminalization.

“There is no data to show incarceration works to decrease new users,” said Sarah Rowan, a Denver Health physician.

“There’s robust data to show these types of supply-side interventions do nothing to decrease drug use,” added Sarah Axelrath, a physician who works with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. “Arresting people who are distributing and focusing on other supply side to substance-use disorders does not reduce drug use and does not stop new people from initiating drug use.”

Josh Barocas of the CU Medical School said criminalization “doesn’t work” and that “the best scientific evidence doesn’t support it.”

As he spoke, a man in the audience interrupted him.

“No one wants fentanyl, you f*** idiot,” the man called out.

The man was escorted out of the hearing, and committee chair Rep. Mike Weissman rebuked him and told the audience to be respectful.

Barocas returned to his testimony and argued that the state’s response to the crisis should be based on science, “not anecdotes.” He said fentanyl is ubiquitous in the drug supply and that he hasn’t seen a drug screen without fentanyl in six years.

He and the other two providers repeatedly criticized any new incarceration measures or penalties.

“We’re talking about thousands of people flooding our overwhelmed prison system,” Barocas said. “And what about all those people who are currently addicted and get locked up? They will die.”

Axelrath said that individuals with opioid-use disorders are 40 times higher for people recently released from incarceration than for the broader population.

“As written, this bill will make felons of my patients,” Axelrath said.

The committee’s vice chair, Tripp, asked Rowan, who specializes in infectious diseases often spread by injection drug use, if all drug use should be legal.

Rowan said she isn’t comfortable weighing in on the question but added, “I absolutely think within any setting that cares for people who use drugs, we need trust, and trust involves openness about drug use.”

Hearing on fentanyl bill begins

Members of the House Judiciary Committee began hearing House Bill 1326, the sweeping legislation aimed at confronting Colorado’s fentanyl crisis, this afternoon.

The House made one major change to the panel: Rep. Leslie Herod, D-Denver, replaced Rep. Steven Woodrow, D-Denver, on the judiciary committee.

At least 150 people have signed up to testify, according to Rep. Mike Weissman, D-Aurora, the committee chair.

More than a dozen law enforcement officers have also shown up in the full-packed hearing room.

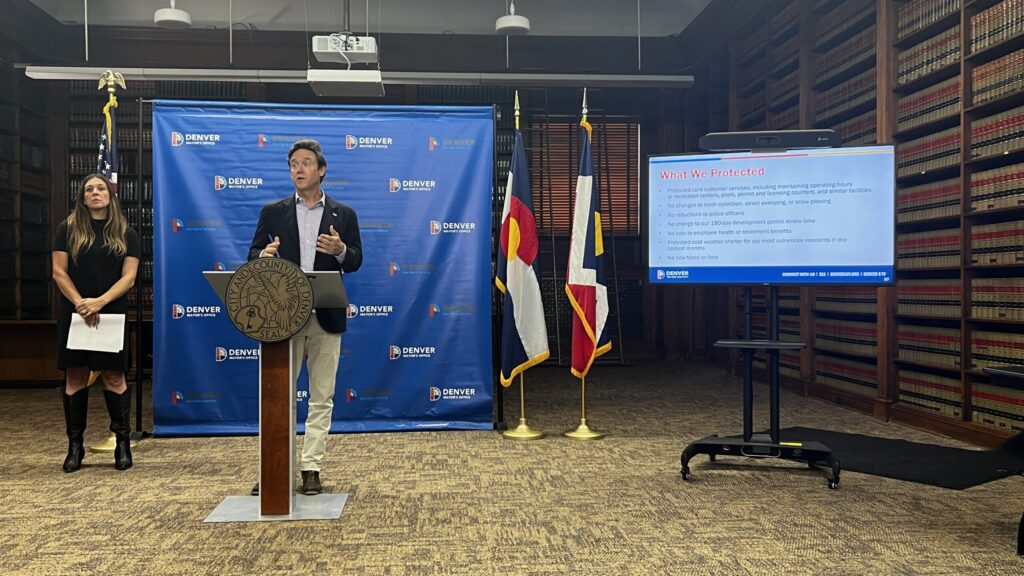

In his opening remarks, bill sponsor and Speaker of the House Alec Garnett, D-Denver, told the committee the bill’s No. 1 goal is to save lives.

Everybody knows how potent fentanyl is, Garnett said, adding, “It’s blanketing our country.”

“We have to move forward on a comprehensive approach,” he added.

Synthetic opioids are the future of street drugs, Garnett said, calling it a “scary reality.” HB 1326 will get resources on the ground.

“It will make sure Coloradans understand the changing environment on the street around fentanyl,” the speaker said, adding HB 1326 will deploy resources on the ground. “The resources to address the problem will not be enough, but it’s more than what we’ve seen in the past.

Among the first to testify during the hearing were three families who lost loved ones to fentanyl overdoses, often not knowing they were taking fentanyl and not another drug.

Matt Riviere lost both his sons, ages 19 and 21, on the same night to fentanyl.

The elephant in the room is the possession piece, said Rep. Kerry Tipper, D-Lakewood, who sought the families’ opinions.

Riviere said 4 grams is way too much.

“We believe the possession limits need to be greatly reduced,” he said.

Tipper agreed that 4 grams of pure fentanyl is too much, but said she does not want felony charges for those who are using drugs laced with fentanyl.

Jessica Chavez, whose daughter died from taking a Percocet-laced fentanyl pill, told Tipper she wants whomever sold her the pill to be held accountable.

Riviere said he doesn’t want to see casual users charged with a felony. What the families want, he said, is “for people to get help and not be put behind bars for bad choices. But the 4 grams is for those who intend to distribute and are killing our youth.”

Debate focuses on fentanyl possession as Democrats appear open to lowering felony threshold

Democrats appear to be open to the idea of lowering the threshold for a felony offense for drug possession to 1 gram, instead of the current 4.

The idea, if adopted, moves a sweeping legislation aimed at confronting the fentanyl crisis closer to the position of law enforcement advocates, although the latter still insist that any possession of fentanyl should be treated as a felony, given how the deadly the drug is.

Democrats, however, seek caveats in exchange, while law enforcement groups maintain the change is insufficient.

“Despite statements from Speaker (Alec) Garnett, the County Sheriffs of Colorado, Colorado Association of Chiefs of Police and Colorado Fraternal Order of Police support the goals of HB1326, including the harm reduction provisions. However, we believe that any amount of fentanyl call kill,” a spokesman for the groups said. “This legislation needs to be amended so that possession of any amount will be a felony. We look forward to working with the speaker and committee members to accomplish this and keep the bill moving ahead.”

Advocates seek to persuade Colorado legislators tackling fentanyl bill today

It remains to be seen what changes – if any – members of the House Judiciary Committee will ultimately adopt following this afternoon’s hearing, which is expected to attract testimony from law enforcement advocates, who are seeking harsher penalties for fentanyl possession, and criminal justice activists, who argue that the “tough on crime” approach has failed to solve Colorado’s drug overdose epidemic.

What’s clear is that an increasing number of Coloradans are fatally overdosing with fentanyl with each passing year, and fatalities have exploded eight-fold since 2018 alone, state data show. The grim trend already triggered a public outcry, and the suspected overdose deaths of in the last several weeks intensified the discussion about what should be done to address the spiraling crisis.

A 2019 bill that lowered the penalty for possession of less than 4 grams of Schedule II drugs, which includes fentanyl, is also drawing intense public scrutiny, with some partly blaming it for the deadly crisis and others arguing that view is simplistic, given how complex the issue is.

Indeed, fentanyl’s unique placement within the drug trade complicates any attempt to simply reverse that law: A cheap, synthetic opioid manufactured primarily by Mexican cartels with ingredients shipped from China, fentanyl is more lucrative, more available, more powerful and easier to produce than heroin. It’s also being mixed into other substances, from cocaine and heroin to methamphetamine, which makes using those substances far more dangerous. This also means efforts to curtail fentanyl possession must take into account the other drugs, as well, and those involved in crafting a legislative response have struggled to find an approach amenable to advocates of all stripes.

The debate over House Bill 1326, in particular, revolves around simple possession.

Arrayed on one side are organizations, led by the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, which argue that further criminalization will do nothing to help slow deaths and instead return the state to what they describe as the failed policies of the War on Drugs, waged for decades without preventing the deadly highs. The War on Drugs, they maintain, came at a tremendous societal cost, sending low-level offenders to prison, breaking up families as a result and fiscally burdening local governments as incarceration takes a bigger and bigger portion of their budget.

On the other side stand many in law enforcement, including Attorney General Phil Weiser and trade organizations for county sheriffs, police chiefs, and mayors John Suthers of Colorado Springs and Michael Hancock of Denver, who insist that the current legislation doesn’t go far enough and insist that simple possession of fentanyl should be a felony, given how deadly the drug is.

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com