Families of fentanyl victims tell stories of love, heartbreak and death as policymakers propose solutions to deadly agent

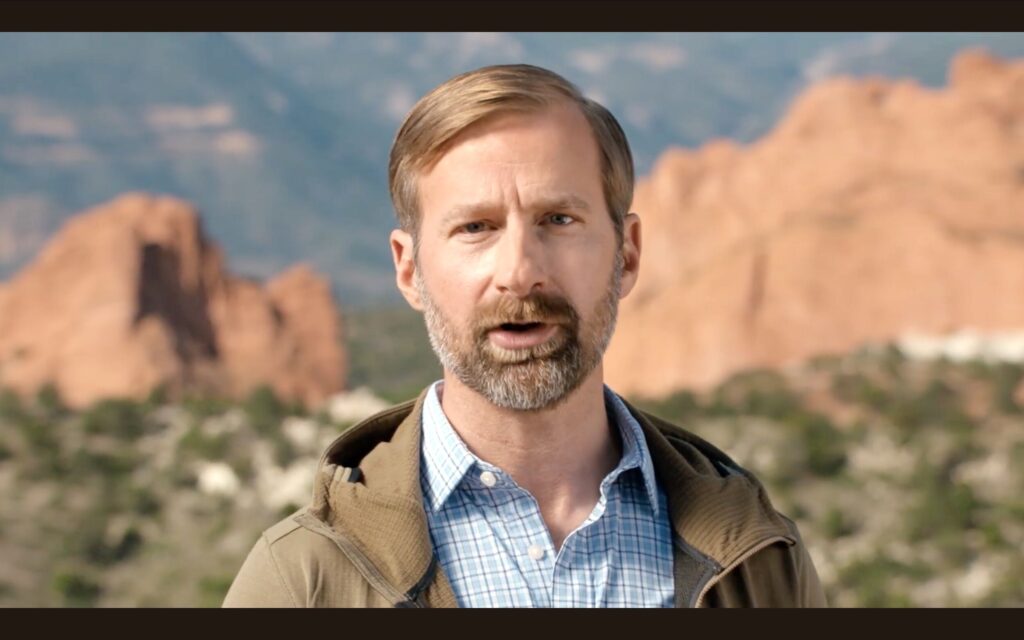

Matt Riviere is the father of two sons, 19-year-old Steven and 21-year-old Andrew. They were just 20 months apart, Riviere said during a March 24 press conference at the state Capitol.

They died the same day.

Both had mental health issues – Andrew was bipolar, Steven struggled with anxiety and depression, he said.

“They were the best of friends and worst of enemies growing up,” Riviere said, adding the boys had a great childhood, growing up in a stable and fun family.

Riviere’s sons started on their road to drugs by using flavored vape, which turned to vaping nicotine, then to pot, then to dabbing and then finally to trying oxycodone.

Riviere said the pills were counterfeit and laced with fentanyl. His sons both died on July 25, 2021.

Every day he sees his son’s pictures – from when they were babies to when they became young, rambunctious boys, and finally when they became adults. Their urns on his fireplace constantly remind him of how their lives were tragically and unexpectedly taken, Riviere said. They would have been the first to admit they made a stupid choice, but they never should have died from experimenting with what they thought was a non-deadly drug, he said.

“They were poisoned, killed and murdered by people who have no regard for human life,” Riviere said.

Prior to his sons’ deaths, Riviere said he’d never heard of fentanyl and didn’t know anything about it. Every day since then, he’d see a story about how the drug takes lives. It is now his duty to tell his sons’ story, he said.

Riviere was among more than a dozen families that attended a news conference on Thursday, when officials announced legislation intended to address both the shortcomings in state law, as well as the need for more education and treatment of those who are addicted to the drugs fentanyl is mixed with. The fentanyl legislation comes amid heightened attention to the drug’s increasingly deadly impact in Colorado. Fatal overdoses involving the drug have skyrocketed since 2015, the product of shifting economics and priorities within the illicit drug trade and accelerated by the pandemic. More than 800 Coloradans died after ingesting fentanyl in 2021, according to state data. That represents a roughly 50% increase from 2020 and more than triple the number of deaths from 2019.

The families shared stories of love, heartbreak and death. Some hold out hope that, by telling the stories of their loves ones lost to fentanyl, it would make a difference to a country grappling with the deadly opioid epidemic. They also hope that Colorado’s policymakers would listen, particularly since they see gaps in the pending fentanyl legislation.

Aretta Gallegos of Northglenn lost her 25-year-old daughter, Brianna Mullins, to fentanyl poisoning on April 14, 2021. Struggling to talk about what happened to Brianna, and through tears, she said her daughter was a caring wife, mother and daughter. She did not want to die, and would never have left her son, Aaron, whom she loved more than her life, Gallegos said.

Brianna was sexually assaulted and that trauma stayed with her, leading her down the path to drugs, Gallegos said.

“She looked for ways to numb her pain,” she said, adding alcohol and Percocet filled some of that void.

Brianna finally agreed to seek help, but later that night she died after taking a Percocet laced with fentanyl.

“We wake up every day reliving the same nightmare, that she is gone,” Gallegos said, adding that also came with the knowledge that no one has faced punishment for her death. Gallegos said the authorities classified her death as an overdose and went on their way.

“Her life matter, and her death mattered,” Gallegos said. “The difference is that Brianna’s death was never investigated.”

That’s despite the fact that the family knows from her cell phone who gave her the pill that took her life, Gallegos said.

If it were your family, Gallegos added, “wouldn’t you want to know who sold them the poisoned pill?”

Gallegos and other families at the news conference pointed to what they believe is one of the gaps in the bill – no money for investigations into fentanyl deaths, such as her daughter’s, and into the drug dealers who peddled the deadly substance.

Fentanyl doesn’t discriminate, Gallegos said.

“It could happen to your child, to any of your children,” she said. “We will not be silent until someone is held to account for these poisonings.”

Andrea Thomas of Grand Junction lost her 32-year-old daughter, Ashley, in 2018 to a fentanyl-laced Percocet that looked just like her prescription.

Since then, Thomas said she tries to bring awareness about fentanyl both in Colorado and nationwide, and founded Voices for Awareness.

No one is immune from fentanyl, she said. People can purchase drugs on social media platforms, such as Venmo and Snapchat, just as easily as they could order a pizza online.

If someone goes onto social media apps, “you’ll find an array of drugs. It’s like a telephone book,” Thomas told Colorado Politics, adding kids, who are unsuspecting, often experiment, and they don’t know what they’re getting.

She views addressing the sale of fentanyl via social media platforms as more of a federal issue. She added that advocates have pleaded with those social media platforms to make changes to safeguard children. So far, however, her group and others have gotten nothing but excuses, she said.

Still, she and many others would like to see a state response to selling the deadly substance on social media, she said.

Tami Gottsegen lost her 24-year-old son, Braden Burks, on Jan. 11, 2019. Braden suffered from sleeplessness, and got what he thought was an oxycodone from a high school acquaintance that would help him sleep. It turned out to be counterfeit oxycodone – and pure fentanyl.

The person who provided Braden with the pill is now in federal prison, Gottsegen told Colorado Politics.

But there are no state laws to hold someone accountable for providing fentanyl resulting in death, so her son’s case was addressed through federal law, she said.

The pending fentanyl legislation at the Capitol seeks to address that issue by going after drug peddlers with harsher penalties. Under the legislation, possession of less than 4 grams of fentanyl is still a misdemeanor under the legislation, but any possession of fentanyl with an intent to distribute, no matter how much, is a minimum class two drug felony. That charge can result in a two to four years in prison, plus fines of $2,000 to $500,000. The charge comes with an sentence enhancement that can add an additional two years.

Gottsegen hopes the bill will make it easier for detectives to find those who distribute fentanyl.

“We need stricter laws,” Gottsegen said. “We can educate our kids, but have to find a way to keep it off our streets.”

She said the bill is a start, but she urges policymakers to review it in a year and see if it’s truly making a difference.

Matt Riviere lost two sons to fentanyl-poisoned oxycodone in 2021, and tells his (and his sons’) story during a March 24, 2022, news conference at the state Capitol to announce a bill addressing fentanyl.

By MARIANNE GOODLAND

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.comMarianneGoodland, Colorado Politics

marianne.goodland@coloradopolitics.com

https://www.coloradopolitics.com/content/tncms/avatars/e/f4/1f4/ef41f4f8-e85e-11e8-80e7-d3245243371d.444a4dcb020417f72fef69ff9eb8cf03.png