With fentanyl deaths on the rise, Colorado Bureau of Investigation seeks more funding and staff

Among the lesser known parts of the public safety package being pushed by Gov. Jared Polis and Democratic lawmakers is ramping up the capabilities of the Colorado Bureau of Investigation and more than doubling the force’s size in three years, particularly as law enforcement agencies grapple with a fentanyl-induced overdose crisis.

That request comes at a time when the bureau is being relied on more and more to handle fentanyl testing and deal with gun crimes.

Polis’ 2022-23 budget request included a bump in funding for the bureau for $6.6 million and the ability to hire 47 additional full-time staffers, part of a three-year phased plan to “rightsize” the agency.

Bureau officials told Colorado Politics said it will improve the services they provide to the entire Colorado law enforcement community.

The Joint Budget Committee unanimously approved the first phase request on March 2. By the end of the next three budget cycles, the agency hopes to be up to 107 staffers, with a total bump in funding at $15.3 million.

It’s a big request for an agency that currently only has 45 agents. That small size means the bureau is severely limited in offering help law enforcement agencies all over the state, supporters of the funding increase said.

The bureau isn’t just the agency that does fingerprinting for background checks for firearms purchases. It also investigates homicides – one of their biggest responsibilities – run a forensics lab that handles drug or alcohol testing, and investigate human trafficking and officer-involved shootings.

The bureau is a “by request” agency when it comes to investigations. It has original jurisdiction in areas such as cybercrimes or pursuing fugitives, but when a law enforcement agency has a major case, such as a homicide or drug issue and doesn’t have the investigative resources or experience, the bureau is called in.

CBI Director John Camper explained that large police departments – Denver or Colorado Springs, for example – have their own investigation units and laboratories to handle crime cases. The bureau plays a bigger role in helping rural law enforcement agencies.

“They really count on us to support or take on those investigations,” Camper said. But the inability to respond to some requests may mean some agencies stop calling for help, particularly on non-homicide cases, he said, adding that’s real problem.

The local agencies do the best they can with what they have, but without investigative backup from the bureau, charges may have to be reduced or dropped entirely, he said.

Take Prowers County, in southeastern Colorado, for example. Sheriff Sam Zordel has a staff of 30: himself, an undersheriff, two office staffers, seven patrol officers and 20 assigned to detentions. His department has no crime lab and no detectives.

In 2017, CBI was the investigating agency for the arrest of Todd Eric Cope, 35, who was charged with a host of offenses, including bribery, drug possession and distribution, and official misconduct. Cope was no ordinary drug dealer. He was a Prowers County probation officer and previously served with the Lamar Police Department. With CBI’s help, Cope was eventually convicted of one count of attempting to influence a public servant, a class 4 felony, and one count of official misconduct, a class 2 misdemeanor. The state POST board stripped him of his police officer certification in 2018.

CBI also was also heavily involved in the investigation of Chris Watts, who was convicted in the murders of his wife and two daughters in Frederick in 2018; the Kelsey Berreth homicide in Teller County in 2018; and, more recently, the Suzanne Morphew homicide that is still working through the legal process in Chaffee County.

Homicide cases take a lot of time and personnel, bureau officials said.

“We are at the bottom of the list” on the number of agents and forensic scientists per million residents, compared to sister agencies around the nation, he told Colorado Politics.

With increased funding from the state, CBI could add a cold case team, Camper said. Currently there’s just one person at the bureau who handles cold cases, and while Camper said that person does a great job, “one person does not make a team.”

A team could provide forensic support or a genetic genealogist for cold cases, he said.

In 2021, KEKB in Grand Junction reported that, since 2011, there are 242 open and unsolved missing persons cases in CBI’s cold case directory, which lacks even photos for most of the missing persons.

Another item on CBI’s wish list is to create a “resident agent” program, under which several agents are placed in several key locations around the state where there is a heavy call volume, Camper said. That would improve response time to those requests, he added.

The CBI’s forensic lab is the primary lab for most agencies in the state, and the caseload is growing, Camper said.

CBI traditionally hasn’t had a role in drug investigations unless specifically requested. The bureau gets far more calls to deal with illicit marijuana dealing, and CBI has two teams – 13 agents total out of its 45 – to tackle such cases.

Bureau officials didn’t contemplate the explosion of the fentanyl crisis when they put together the budget request, Camper said. But it’s now prompting conversations with the Colorado Criminal Defense Bar and lawmakers, eager to find out what help CBI could offer.

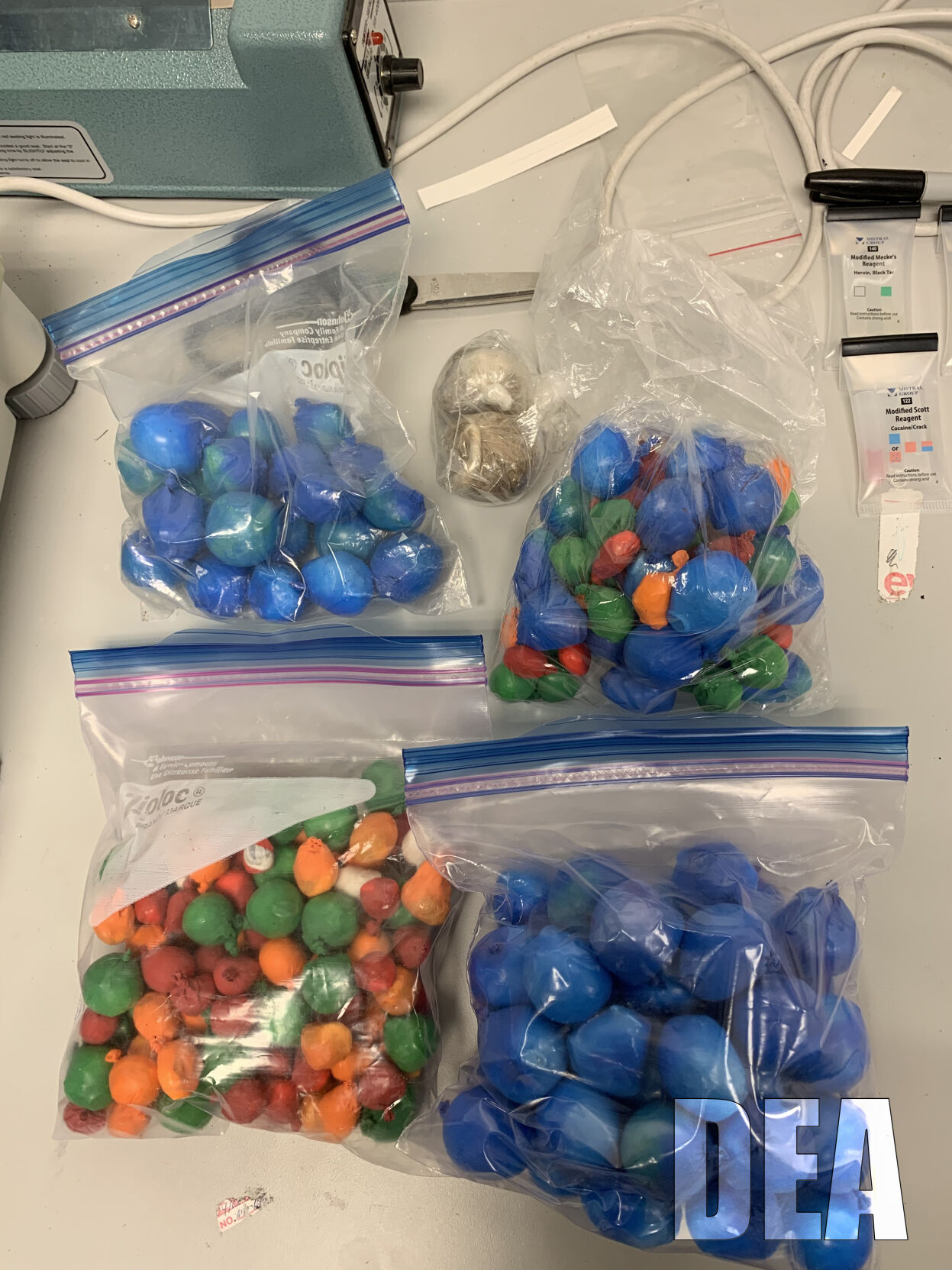

The bureau’s Lance Allen, interim deputy director for forensic services, said his unit can identify what drugs are present and whether something is mixed with fentanyl, which is now common. But testing fentanyl raises safety concerns, as well, because it requires different handling compared to other drugs routinely tested for, Allen said.

He said he recently explained it to a lawmaker this way: normally, the pills are weighed, and then cut in half and the tests are run on half a pill. The pill isn’t crushed, he said, which would put the drug into the air and create risk for lab staff. Charging is based on total weight, not how much fentanyl is present in the drug, Allen explained.

And agencies are increasingly turning to CBI to conduct that testing. Since 2018, CBI has seen fentanyl cases increase by 1,600%, and it went from being a much lower level problem to the third most common drug the bureau identifies behind heroin and meth. And through March 2022, fentanyl has moved up to No. 2.

The budget request includes adding drug chemists to handle the growing caseload, Allen said.

What’s clear is that the bureau is struggling to keep up.

“We have to say ‘no’ to quite a few of them,” Allen said of lab work requests.

To put the issue into perspective, bureau officials noted that CBI has 18 major crimes investigations for the whole state. Lakewood, in comparison, has 45 investigators for a city of 155,000.

Those 18 CBI investigators also face geographic challenges. It might take five hours to drive to pursue a case, and some of those investigations, such as the Watts case, take 18 months to complete.

In 2021, CBI conducted 42 homicide investigations and also probed 16 officer-involved shootings, said Chris Schaefer, CBI’s deputy director for investigations. An agent assigned to a homicide, such as the Morphew case, is working solely on that case full-time, Schaefer said. It’s impossible to guess how long an agent will be tied to a case, and that’s part of the challenge of having a small staff, he said.

That leads to the bureau turning down cases, except for homicides, which they always accept, Schaefer said.

The lack of staff also affects turnaround time, according to Lance Allen, interim deputy director for CBI’s forensic services.

Some testing needs to be done faster than others, such as for DUIs, he said. But the lack of staff in forensic services means they haven’t been able to devote as much time to fingerprint or firearms investigations, and with gun crime on the increase, that’s a problem, Allen said, adding that, as a result, for example, a firearms case can take almost a year to complete, Allen said.

Since 2012, requests for forensics services have nearly doubled, but staffing is down about 7%, he noted.

The bump in funding and staff will increase services in fingerprinting and drug chemistry, as well as DNA analysis, Camper said.

The 2022-23 Long Appropriations Bill is expected to be introduced in the House on March 28.