Judge who slashed jury $1.5 million verdict by 70% acted reasonably, appeals court finds

A Jefferson County judge was justified in reducing a jury’s $1.5 million award to a car crash victim by 70%, the state’s second highest court ruled last week.

Catherine Pisano, who underwent multiple medical procedures and experienced lingering pain after she was rear-ended on Interstate 70 in 2014, asked the Court of Appeals to find that District Court Judge Tamara Russell wrongly decided how much money state law entitled Pisano to receive. Russell lowered the $1,548,000 that a jury had awarded Pisano for her suffering, emotional stress and deteriorated quality of life to $468,010.

The judge had the option of granting Pisano twice that amount, $936,030, but she reasoned that Pisano’s injuries were not “exceptional” enough to warrant the higher figure.

A three-member panel of the state’s Court of Appeals decided Russell had acted within her authority in picking the lower dollar figure.

“Given the conflicting nature of the evidence presented at trial, we are not in a position to second-guess the trial court’s assessment of the circumstances of Pisano’s case,” wrote Judge Elizabeth L. Harris in the Feb. 17 opinion.

Pisano’s appeal raised the question of how trial court judges are supposed to evaluate the proper level of damages a plaintiff should receive when the jury comes up with a figure in excess of the cap under state law. For noneconomic damages – the $1.5 million for pain and suffering in Pisano’s case – the legislature set the maximum amount at $468,010, adjusted for inflation at the time of Pisano’s trial. A judge could separately authorize damages of up to $936,030, but only if there was “justification by clear and convincing evidence.”

Russell, in defending her decision to stick with the legal cap, noted that Pisano’s afflictions were not as debilitating as those in other personal injury cases. Therefore, she was “not persuaded by clear and convincing evidence that plaintiff’s injuries have risen to the level of exceptional circumstances justifying exceeding the statutory cap.”

Pisano argued that the law did not mention “exceptional circumstances,” and Russell merely had to decide whether the evidence the jury heard justified the higher amount in a clear and convincing fashion. The Colorado Trial Lawyers Association submitted a brief to the appellate court in support of Pisano, arguing that Russell undermined the jury by concluding for herself whether Pisano’s injuries were severe enough.

The Court of Appeals panel was critical of that interpretation during oral arguments.

“In the absence of any kind of standard (written into the law), doesn’t that suggest that the trial court can exercise its discretion?” asked Harris.

But the judges were also skeptical of defendant Leann Manning’s interpretation of when judges should exceed the $468,010 cap.

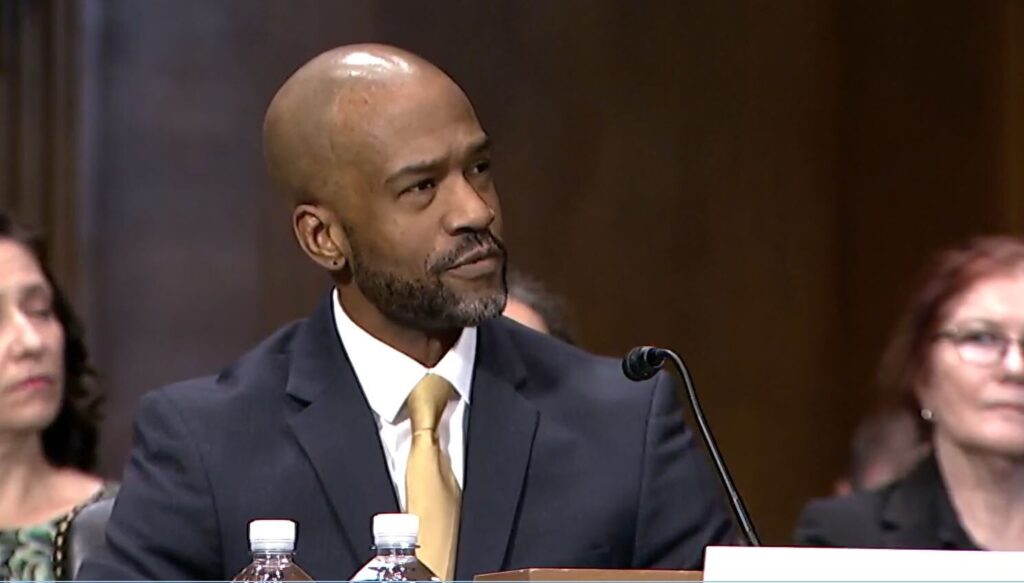

“The judge, when determining whether the cap should apply, is dealing with public policy and is instead answering the question of whether allowing this person who has X damages to have this much (money), whether that would be a miscarriage of justice,” said Evan Stephenson, the attorney for Manning.

Judge Lino S. Lipinsky de Orlov noted that the phrase “miscarriage of justice” does not appear in the law either.

“Are you arguing the trial courts have unfettered discretion?” he asked.

Ultimately, the panel agreed that Russell was within her authority to determine whether Pisano’s injuries constituted “exceptional circumstances” to exceed the cap. Trial courts, wrote Harris, can consider “any factors” that are relevant. She added that any award that exceeds $468,010 is necessarily an “exception” to the normal limit.

In addition to finding that judges do not have to tether their decisions to the jury’s work, the panel decided that Pisano’s injuries did not necessarily fit the description of exceptional circumstances. Although the jury heard testimony that there was “no more happiness” with Pisano and that laying down in bed was the “only time” she is not in significant pain, there was also evidence that Pisano was able to take care of herself and her family, and that she continued to excel at her job.

The Colorado Civil Justice League, Colorado Defense Lawyers Association and the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies had weighed in to the Court of Appeals on Manning’s behalf. They noted the state legislature had imposed damage caps in the 1980s to help make insurance policies more affordable.

In addition to the $1.5 million for her pain and suffering, Pisano’s jury awarded her $634,767.11 in economic damages. She had also requested more than $4 million for her physical impairment, but jurors declined to provide anything in that category.

As of Jan. 1, 2022, the cap for noneconomic damages is now $642,180, which a judge may increase to a maximum of $1,284,370.

The case is Pisano v. Manning.