In data access lawsuit, Colorado AG’s office is contradicted by its own records

In October, when Denver County District Judge J. Eric Elliff upheld records request denials for data that would show identifying and employment data for every law enforcement officer who has been certified to work in Colorado, he partially based his decision on testimony from Attorney General Phil Weiser’s office that the state’s system for maintaining this information did not have the capability to produce such data.

The agency that certifies police officers and has the power to discipline them in some cases by suspending or revoking their state licenses is the Colorado Peace Officers Standards and Training Board, or POST. It’s housed within the state Department of Law, run by Attorney General Weiser.

Now, records obtained from Weiser’s office show that its database system not only has the capability to export data, but that that function was part of the state’s requirements for vendors when it was searching for a new database company.

Natalie Hanlon Leh, who has served in the number two position in the Department of Law since 2019, testified that the IT department that services POST informed her that “it would be very burdensome and not possible” to query that information from the state’s new database, made by Benchmark Analytics, a firm run by former Chicago police and education officials. “My understanding is you can’t just export data from these databases,” she said.

That appears to directly contradict the state’s own request for proposals that prompted Benchmark to submit a bid, and Benchmark’s bid itself. In the RFP for a new system to manage police certification and employment data, the state specifically included requirements that “all data fields shall be searchable and reportable” and that the system needs to “allow all reports to be exported to common formats,” including Excel spreadsheets.

In its bid, Benchmark expands on those requirements. “The Benchmark Reporting and Analytics engine provides agencies with flexible access to the data that agencies enter into the Benchmark platform,” the firm writes. Its “ad-hoc editor” provides users “the ability to create spreadsheets, charts, and all of the drill-down/cross-filtering functionality contained within the standard reports.”

Benchmark, which launched in 2016 after being developed by researchers at the University of Chicago, is a relative newcomer to law enforcement software, but already holds contracts with the New Hampshire and Minnesota POST agencies, the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office, and the Dallas and Nashville Police Departments, among others. In addition to certification databases, it offers agencies features including Internal Affairs tracking and Early Intervention Systems. It also recently launched a risk solutions suite of products. Its contract with POST, signed in January 2020, is worth nearly $2 million over its six-year lifespan if all planned extensions are used.

Easy editing of reports generated from queries of the Benchmark database is also a clearly outlined feature of the software – something that Hanlon Leh also testified was burdensome for the state. “Our reporting tool allows permissioned users to export reports in a variety of formats,” according to Benchmark. The tool can produce “a fully editable file that can be saved or manipulated by users” in multiple formats.

Yet to hear Hanlon Leh’s testimony, one would believe it impossible to query Benchmark’s database and export that information into a spreadsheet format – a normal function of essentially any enterprise database software. When asked who she consulted with regarding Benchmark’s capabilities, the only person she named was Erik Bourgerie, POST’s executive director.

Bourgerie is a former longtime deputy and detentions supervisor with the Summit County Sheriff’s Office who joined POST in November 2017, and does not purport to have database skills. During his decade at the helm of the office’s detention division, the sheriff’s office faced multiple lawsuits alleging negligence and excessive force within the jail, which led to several detainee deaths and multimillion-dollar settlements.

Hanlon Leh’s testimony about POST’s previous database vendor seemed also to be undermined by records her own office provided. “We can’t just export a record” that would be responsive to the requests made by The Gazette and Invisible Institute using the old software, Acadis, which was in place at the time of the requests, she testified.

However, Acadis contradicts Hanlon Leh directly in documents submitted in response to the RFP that Benchmark ended up winning. Users with the proper authorization can use Acadis to “export records to reports and .CSV files for use by Excel and other spreadsheet applications,” and can use queries to “create custom exports for any and all data fields within Acadis.”

Other states that use Acadis have been able to release police certification data in spreadsheet form to the Invisible Institute, though it’s possible that different agencies have access to different features. A total of 27 states released or agreed to provide access to police certification databases in response to records requests made by the Invisible Institute in 2019.

The release of the data is in the public interest because they can be used to show officers who have moved from department to department, or departments that employ officers with checkered pasts, according to Jeffrey Roberts, executive director of the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition.

A 2015-16 series of reports in The Denver Post by Christopher Osher, now of The Gazette, exposed a lack of oversight exercised by POST that allowed rogue officers – some with criminal records, others who had been fired in other states – to bounce around the state, leaving trails of misconduct in their wake. Those reports, which were produced without the benefit of the state’s certification data, led to a change in state law meant to prevent this movement.

However, the law did nothing to ensure public access to certification data. Similar reporting and research has been done in Washington, Illinois, Minnesota, Louisiana, Wisconsin, California, Alaska, and Florida, and nationwide reports on the issue have been published by the New York Times, Washington Post and Associated Press.

In addition, the data could show which departments in Colorado are having trouble hiring officers, as many law enforcement agencies have in recent years, Roberts said.

Because Judge Elliff previously ruled that the requests from The Gazette and Invisible Institute should be governed by the restrictive Colorado Criminal Justice Records Act, not the more transparent Colorado Open Records Act, the most important question he considered was whether Hanlon Leh abused her discretion in denying the request – not whether POST had the technical ability to produce the data.

However, he made clear that POST’s claimed technical limitations played no small part in his decision.

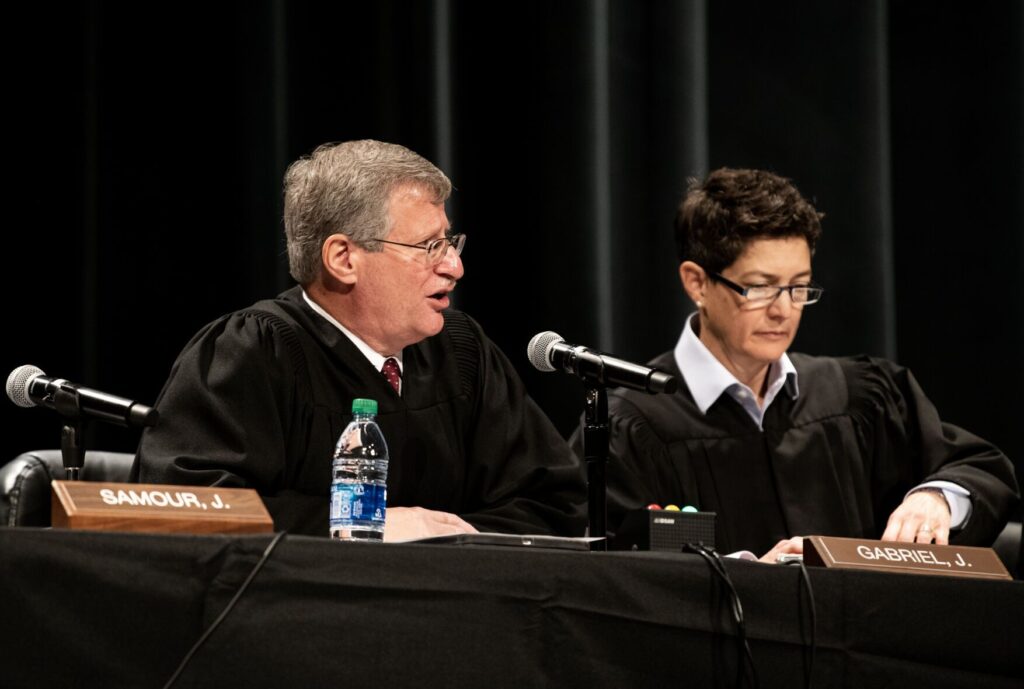

“We heard that the particular database which is now known as Benchmark was not capable of running queries,” he said during his October oral opinion. “What (Hanlon Leh) testified to is that under using that program, it would take literally hundreds of hours of POST staff time to call up, look at, redact, and produce in some form or another the information that the Plaintiffs are requesting.” He found that there was “credible evidence” that fulfilling the request would be an “undue burden” for POST.

He added that “it would have been great” to have testimony from Benchmark or a POST information technology worker to confirm Hanlon Leh’s understanding of Benchmark, which she said several times was not based on firsthand knowledge.

Lawyers with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, who are representing the Gazette and Invisible Institute pro-bono, have filed an appeal of Elliff’s rulings classifying POST data as being governed by the CCJRA rather than CORA, and that Hanlon Leh did not abuse her discretion in denying the requests.

Editors Note: The Invisible Institute is a nonprofit journalistic production company focused on public accountability. Based on the South Side of Chicago, its investigative journalism has won awards, including a Pulitzer Prize in National Reporting, an Emmy in Outstanding Investigative Documentary and a National Magazine Award in Podcasting, among others. Its Citizens Police Data Project, which makes decades of Chicago police misconduct data and documents publicly available, was awarded a Sunshine Award by the Society of Professional Journalists, and is held up as an example of use of police data for the public good. Find its work at invisible.institute. The Invisible Institute is co-plaintiff with The Gazette in litigation seeking to make public Colorado’s POST data detailing employment of police officers in Colorado.