Colorado town grieves after deadly avalanche tore out the heart of its community

Last Saturday, 49-year-old Adam Palmer of Eagle updated his Facebook profile photo to an image of him and a group of his ski buddies. They’re suited up and striding along the edge of a snow-banked mountain road, skis balanced on shoulders and gazing off into the distance, seemingly at the wonderland of backcountry powder that awaits.

“Looks like an album cover,” wrote a friend later that day, commenting on the photo.

“So jealous!” wrote another.

Another, marveling at all the snow, wanted to know, “Is that Vail or BC?”

Just after 7 a.m. Sunday, Palmer responded: “Silverton.”

By Tuesday morning, as news of a deadly avalanche in a backcountry ski slope near that tiny mountain town in the San Juans began to spread, the tone of the comments turned to worry, then desperate hope.

“Are you back?”

“Praying you guys are safe.”

By then, the families and close friends of Palmer, Andy Jessen and Seth Bossung were facing an awful reality, in which ice, snow and time were likely the only things that remained between them and confirmation of a nightmare.

After three days and long hours excavating cementlike snowpack that broke shovels and required chainsaws, search and rescue crews on Wednesday finally reached the bodies of Palmer and his two friends. The men died late Monday afternoon when their party of highly experienced alpine athletes was caught in an avalanche while skiing near Ophir Pass.

Palmer, Jessen and Bossung, all of Eagle, left behind not only grieving families and friends, but a hometown in shock and struggling to process the loss of three men who loved and served their communities, both on and off the clock, who were “true contributors to Eagle’s DNA,” as one friend put it on Facebook.

“Our hearts are heavy with the loss of these three men. Their contributions through their work in local government and local businesses, as well as their personal passions and their impact on the friends and family members they leave behind, have helped shape the community in ways that will be forever lasting,” said a joint statement from Eagle County and the town of Eagle, which received the families’ permission to release the victims’ names Wednesday so the community of Eagle “can all openly acknowledge their deaths and grieve together.”

Palmer, a husband and father of two, was a member of the Eagle Town Council and played a “crucial role” in the county’s COVID recovery response team, ensuring businesses had the resources for state and federal grants and the information they needed to navigate the pandemic, said County Manager Jeff Shroll.

A force for eco-focused change, Palmer was Eagle County’s sustainable communities director, where he put his sly grin and good-natured persuasion to work for his neighbors, and the environment.

“Adam was the Norse god Loki of Eagle County, the coyote of the climate movement and of our community,” wrote his friend and fellow climate warrior Auden Schendler in an essay last week for Mountain Town News. “I never knew someone to so persistently care about the success of others, to so joyously celebrate and foster their progress, even as he himself excelled.”

Seth Bossung, 52, was an architect and Colorado College graduate who worked under Palmer in the sustainable communities department, and founded Intention Architecture to examine “the relationship between us, the natural world and our built environment.” He leaves behind a wife and two children.

“We worked closely together for three years, growing the Energy Smart Colorado program together, supporting each other along the way. We shared that passion/desire for a deeper understanding of systems and buildings as well as helping people,” said Bossung’s friend, John Ryan Lockman, in a memorial on Facebook. “The Eagle County community will never be the same without these three.”

Andy Jessen, 40, co-founded the town’s Bonfire Brewing, and was a council member and mayor pro-tem. He also played a significant role in the development of Eagle’s new River Park.

“Over the last decade, Bonfire Brewing founders and community evangelists Andy and Amanda Jessen have taught the Eagle community what it means to gather ’round,” said a tribute on the GoFundMe page set up for Jessen’s family. “Andy is a steward for conservation, an ambassador of our town, a people-focused leader, an engaged friend and family member, the proudest of dog dads and the sincerest of partners to the love of his life Amanda.”

All three men were passionate about climate issues and the outdoors, and about sharing those passions with others through their joy, words and lots and lots of “amazing” photos, Shroll said.

“I’m athletic and, god, I could never keep up with those guys. I don’t know what they do that they weren’t better at than me. From skiing to kayaking to mountain biking. They were all avid. And I’m talking expert stuff…,” Shroll said. “They did this a lot and this was part of who they were. They loved being outdoors. They knew all of the issues that go along with that.”

Skiing the remote backcountry around Ophir Pass, between Silverton and Ophir, is more than a day trip. The closest roads are closed in winter, and well-prepared adventurers park off a forest route and hike up to a place called OPUS Hut, where they can overnight. From there, they wake at dawn and head out.

On Feb. 1, Palmer, Jessen and Bossung were among a group of seven who were skiing near the treeline in an area known as “The Nose,” where the ski run drops to a creek and gully, according to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center. The group’s passage triggered the slide as they traveled through a layer of fresh powder that, unbeknownst to them, was essentially floating on a base of older “rotten” snow. The massive slab separated and four members of the group were caught, carried down the slope and fully buried.

The unharmed members of the party were able to dig out one of the skiers, who had only minor injuries, but Palmer, Jessen and Bossung were too deep.

The men all carried packs with avalanche safety gear and wore transceivers that emit a signal letting others know where they are under the snow, but because of the depths – up 20 to feet – it was impossible to pinpoint their exact location.

“The efforts that were made, from what I heard from the people who were there when the incident happened, were astronomical. They worked and dug for hours, into the darkness of the night, until they had to stop and wait for an organized rescue party to assist,” said Matt Steen, snow safety director with Helitrax, the Telluride-based heli-skiing operation that worked with search and rescue on avalanche mitigation and recovery.

The search and recovery was a massive, multiagency effort that lasted three days. The men’s bodies were found Wednesday and they were transported by Helitrax to Silverton the following day, as soon as weather conditions made the flight possible.

“Our team broke eight shovels, borrowed snowmobiles, chainsaws, helicopters, rescue sleds and La Plata SAR even brought up a snowcat as well as team members,” according to a Facebook post from the Office of Emergency Management of San Juan County.

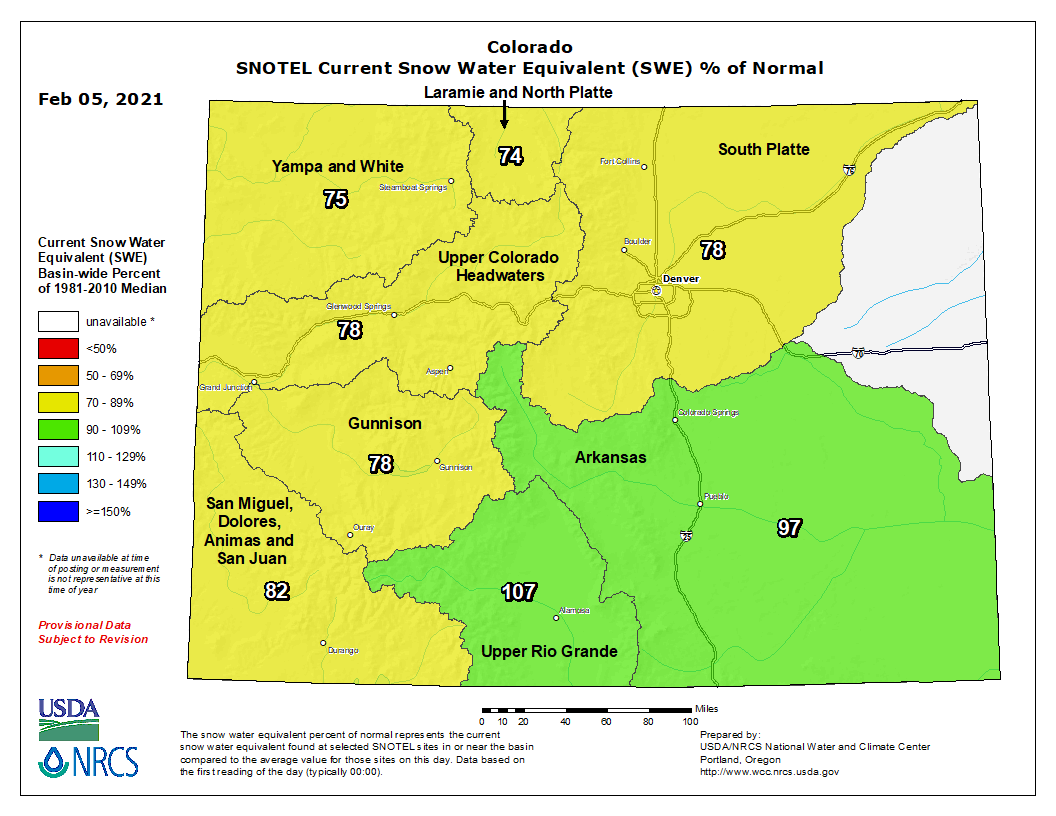

??

The avalanche risk assessment for that area at that time was a level 3 out of 5, meaning that human-triggered slides were likely, said Ethan Greene, director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center.

The avalanche was the deadliest since 2013, when a group of skiers and snowboarders crossed the Sheep Creek drainage gully north of Loveland Pass and triggered a massive avalanche. All six were buried and only one survived, according to CAIC.

Avalanche conditions are based on an area’s terrain and snowfall, but also the weather conditions throughout the entire season, which affect how the layers of snowpack age and interact with one another.

If the conditions are right, the weight of a hiker or skier – or a vibration that can travel “great distances” – can set a million-ton slab of snow crashing down, at speeds of more than 200 mph.

That’s what happened near The Nose last Monday, and what’s happening around Colorado, during a winter that’s set records for human-triggered avalanches.

The number of people killed by avalanches this winter in Colorado rose to eight on Thursday when a skier was caught south of Vail after exiting the Vail Ski Area through a backcountry access gate. Other riders found the skier and performed resuscitation efforts, but they were unsuccessful, according to the CAIC. Rescuers said the avalanche in an area known as “Marvin’s” was 700 feet wide and ran 1,000 vertical feet.

Due to this year’s conditions, Greene and his team are providing information on the higher-than-normal avalanche risk in the hope that outdoor enthusiasts can make informed decisions.

“We’re not advising people to avoid the backcountry. We are warning people how dangerous the avalanche conditions are and they really need to choose a plan for their day and a recreational goal that fits those conditions,” he said. “Depending on what people are willing to accept in terms of risk, reward – that’s really a personal decision.”

??

As avalanche experts struggle to get that message out, in a deadly season that’s not over yet, Eagle is struggling to process what’s been lost, and how to say goodbye.

Friday, Bonfire Brewing launched what will be a regular gathering, Aloha Fridays in honor of Palmer’s affinity for Hawaiian shirts, to celebrate the memories of Jessen, Palmer and Bossung, and raise money for the avalanche awareness center. That night, an impromptu gathering sprung up at River Park, with music pumped through Palmer’s locally famous speaker and attendees taking turns to pen messages to their lost friend on the riverboard he’d nicknamed “The Slasher.”

On Wednesday, Shroll said he held a Zoom call with 120 county employees to encourage everyone to seek resources through Eagle Valley Behavioral Health to deal with processing the tragedy, which in a single blow reduced the town’s elected council from seven to five members. He also knows they’re not the only ones who are hurting.

“What I am really impressed by is how our community is banding together,” he said. “This has rocked the entire community and I suppose in the middle of a crazy pandemic and coming off a horrendous virus season that we all struggled with, all those guys played a role in helping out with, just to see our community rally around our families and rally together to move on in some form and keep their memories alive. That’s why I love small towns, that’s why I love Colorado so much.”

Shroll said he expects there will be “several opportunities” in the coming weeks for the community, both geographic and in spirit, to gather and celebrate the lives that were lost.

Until then, and as it deals with the national media attention the tragedy brought, this tight-knit town is closing ranks on its grief, as it tries to find a way through.

“There are pros and cons to living in a small town. And certainly one of them is you get to know your neighbor and by doing that, we have a history in Eagle of rolling up our sleeves, helping each other in every way,” said Mayor Scott Turnipseed. “And I guess I am asking the community to help families that need help, but at the same time, right now be respectful of their privacy. They are going through a lot right now.”