A Colorado county’s sheriff’s office opts to enforce immigration laws

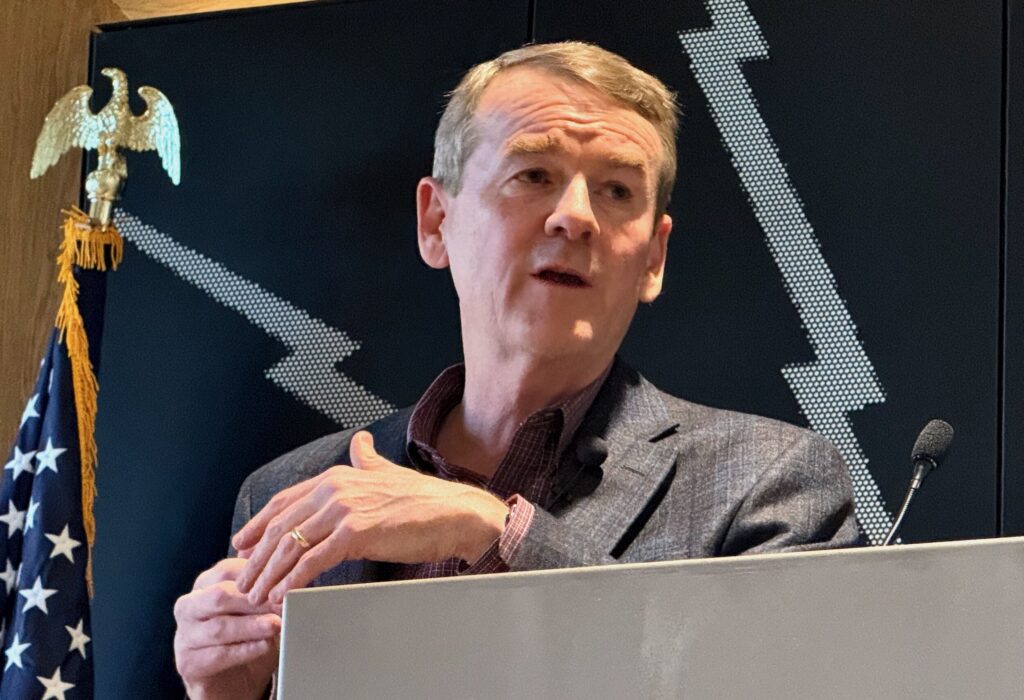

Teller County Sheriff Jason Mikesell is doubling down on efforts to enforce immigration laws as border crossings have become a hot issue in national politics.

Mikesell has signed an agreement with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, that will allow two members of his staff to be trained to interrogate suspected undocumented migrants at the county jail, issue arrest warrants for immigration violations and complete paperwork to begin the deportation process.

In a letter to ICE’s deputy director last February, Mikesell said the program could help him combat “organized criminal activity by out of state cartels and illegal aliens who are taking advantage of Colorado’s recreational marijuana laws to operate sophisticated illegal grow operations.”

The sheriff’s adoption of the program comes amid calls by President Donald Trump for a $5.7 billion wall on the southern border to thwart illegal immigration. Sheriff’s Cmdr. Greg Couch said it’s Mikesell’s latest partnership with ICE to rid the community of undocumented migrants, who the sheriff says are committing crimes.

After Trump signed a 2017 executive order to bolster immigration enforcement, participation in the 287(g) program more than doubled, from 36 to 76 law enforcement agencies nationwide, reports the Department of Homeland Security.

The report last fall found that ICE failed to adequately plan for staffing and technology upgrades needed for the expansion.

The El Paso County Sheriff’s Office abandoned the same program in 2015, after nearly two decades, amid concerns that it drained resources, lacked proper federal oversight and led to profiling of immigrants.

No other Colorado law enforcement agency now participates in the 287(g) program, the ICE website says.

The Teller County program differs from some earlier versions, which allowed local officers to search their community for undocumented migrants. Under the new program, the trained officers can only exercise that authority in jail, so only jailed suspects’ documentation would be checked, Couch said.

Still, 287(g) can erode trust between police and the immigrant communities they serve, critics say. Migrants might hesitate to report crimes if they know their law enforcement agency is “part of the deportation pipeline,” said Mark Silverstein, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado.

“Undermining public trust undermines public safety, because public safety depends on witnesses and victims calling the police,” Silverstein said.

Mikesell’s office also has an agreement with ICE to jail suspected undocumented migrants at that agency’s request. The practice of honoring such “detainer” requests, which are not signed by a judge, is at the center of a lawsuit that the ACLU filed against his office last summer. The lawsuit was brought on behalf of Leonardo Canseco Salinas, who was held at the Teller County jail in Divide on an $800 bond over two misdemeanors involving the alleged theft of $8 from a fellow gambler at a casino.

Silverstein said Teller County’s participation in 287(g), which will allow the Sheriff’s Office to generate the detainers, does not change the ACLU’s argument that Colorado law does not recognize detainers as proper justification to hold an inmate who has posted bond or resolved his criminal case.

The Sheriff’s Office conducts routine questioning during jail bookings, Couch said.

In the past, if anyone was suspected to be undocumented, the office would notify ICE, which sometimes would ask that the person be kept in jail so that federal authorities had more time to pick them up, Couch said.

Under 287(g), the trained staff members will be able to confirm if someone is an undocumented immigrant and draft charging documents for ICE.

In August, 4th Judicial District Judge Lin Billings-Vela tossed out a motion by the ACLU for a preliminary injunction to bar the Sheriff’s Office from honoring the detainers while the case was pending. Since Canseco’s release last summer, the prospect of a final court ruling on honoring detainers has been in doubt, Silverstein said.

The addition of the 287(g) program complicates the ACLU’s argument because it was not in place when their client was being held, he said.

In another ACLU lawsuit challenging El Paso County Sheriff Bill Elder’s authority to honor ICE detainers, a judge ruled in the civil liberties group’s favor, saying the practice was illegal. Elder’s office is appealing, and a decision by the appellate court could resolve the issue statewide, Silverstein said.