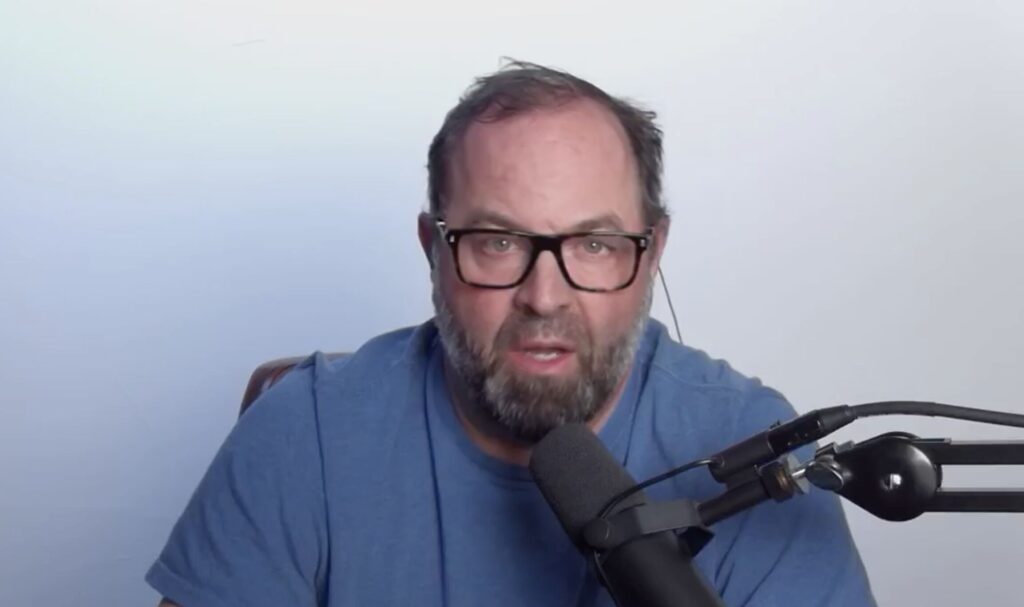

Colo. Secretary of State Wayne Williams leaves office as he entered: Building bridges

In a year of political upheaval, Wayne Williams – the man many regard as Colorado’s anti-politician – lost his job as secretary of state on election night.

Williams paid a price for his Republican ties, losing to a virtually unknown Democrat – voting-rights attorney Jena Griswold, who has never held elective office – even though his politics are best described as purple.

It’s a strange thing for a man who shunned a push to put him in the governor’s race. Williams declined to seek the higher office, he says, because he just doesn’t like politics that much. He loves policy but could live without the partisan bickering.

“For me, it’s more about getting things done,” he said. “I can rail against the pothole, or I can fix it. I’d rather fix things.”

But Williams, from his post as the state’s top vote counter, says Colorado has entered a period of rigid partisanship with the blue wave that swept the GOP from every statewide office on the ballot.

“For the first time in state history, we saw a straight, pure party-line vote,” said Williams, a former El Paso County commissioner and clerk.

Williams was defeated for re-election by 155,930 votes as of the Nov. 10 vote tally from his office, despite attracting more votes than he did in 2014.

Coming off a year when he gained national praise for running the state’s least-partisan partisan office, the father of four says he is too busy counting votes from the last election to be bitter. He still claims Democrats as friends and is preparing his office for a smooth handoff to his successor.

In the days since the election, his cellphone has buzzed with condolence calls and texts from across the political spectrum. Democrats have expressed regret, he said.

“And,” he said, “I got a very nice note from [conservative activist] Douglas Bruce.”

Williams rose to become the state’s top-ranking Republican elected official by smoothing over differences with opponents.

It’s a skill he picked up as a boy in Front Royal, Virginia, a blue town in a blue state where Democrats had run local politics since the Civil War.

Williams, 55, was worried at a young age by the racist legacy of the local southern Democrats. They were the bunch who battled against desegregation. Raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Williams saw racism as a sin and Republicans as the party of emancipation.

“At 17, I organized about 70 kids on election day,” he said. “We stood outside every polling place and passed out literature. For the first time since Reconstruction, Republicans won the county.”

It was amid the Reagan Revolution, now seen as a national highwater mark for conservative politics, that Williams learned to work across party lines. He points to President Ronald Reagan’s close relationship with Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neil as a guiding example.

After high school, Williams headed to Brigham Young University and a Mormon mission in Alaska. Young Mormon men are sent afield to share their faith, and they learn to accept frequent rejection with a smile.

“It is part of my faith,” he explained. “When someone disagrees with me or attacks me, I reach out to them.”

After BYU, Williams headed to the University of Virginia’s law school. He married his wife, Holly, who he says is the real politician of the family. She was working on Capitol Hill in Washington when they dated, helping craft policy for a Republican lawmaker.

They have formed a unique political union. On the day he was voted out of office, she was elected an El Paso County commissioner.

The couple first moved to Utah after their time back east, but Williams was on the lookout for a place to call home. He found it in Colorado Springs, where he began a law practice and bought a home in Briargate.

Williams says he fell in love with the Colorado Springs region, where he settled in with his growing family. He fell in love with politics here, too.

In the mid-1990s, the GOP in El Paso County was in a time of transition. Old-timers in government faced losing their jobs with Amendment 17, which set term limits. Urged on by his law practice partner, now state Sen. Bob Gardner, Williams got involved with the local branch of the GOP.

As he rose in the Republican ranks, Williams sought advice from an unlikely source: former state Democratic Party Chairman Howard Gelt.

Gelt warned Williams about deep divides in the local GOP, where abortion-rights advocates and evangelical Christians vied for power with military hawks, moderate allies of President George H.W. Bush and the newcomers to the conservative movement inspired by the 1992 campaign of billionaire Ross Perot and his Reform Party.

“He told me, ‘You don’t know what you’re getting into,'” Williams recalled.

But Williams was undaunted. All he had to do to become the party chairman was to get the warring sides to become allies.

He started by befriending leaders from every camp – Colorado Springs-based Focus on the Family to fiscal conservatives.

“I did it by trying to give everyone a voice,” Williams said. “It was getting people to work together.”

Williams focused on process and accomplishments, quietly growing the local party’s ground game.

By 1998, the newly united party put on a show of force at the ballot box. Democrats had held the keys to Colorado’s governor’s mansion since 1974. El Paso County, with nearly 70 percent of ballots favoring the GOP, was critical in delivering an 8,000 vote victory to Republican Bill Owens, who went on the serve two terms as governor.

Williams said his mantra for Republicans here sealed the win.

“The role of the party is to bring people together.”

The victory gave Williams a shove toward elective office, too. In 2002, he was elected to the first of two terms as an El Paso County commissioner.

Williams used his commission seat to push for highway work, driving a successful ballot measure that created the Pikes Peak Rural Transportation Authority. That meant being a Republican and backing a tax increase, drawing the ire of Bruce, the state’s top anti-tax advocate, father of the state’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights and a man who remains notorious for campaign rancor.

Williams also worked with Democratic Gov. Bill Ritter in Denver to gain highway cash.

But somehow, Bruce and Williams got along.It was hard to dislike a man whose political campaigns reflected his politics, low-key affairs that accentuated the positive and never mentioned opponents.

“I never talk about them,” Williams said of political opponents. “As a rule, I think your campaign should talk about what you plan to do.”

Williams fell in love with the clerk’s job. It was essentially like running a business, he said. His priorities included easing wait times for taxpayers seeking vehicle tabs and cutting red tape. He virtually dropped out of partisan politics in a bid to remain a fair broker in elections.

“When I stepped into the clerk’s role, it was a different role,” he said.

When Colorado Secretary of State Scott Gessler set his sights on the governor’s office in 2014, Williams decided to take his clerk skills statewide.

He beat Democrat Joe Neguse for secretary of state by nearly 50,000 votes. The two are now friends; Neguse was elected to succeed Gov.-elect Jared Polis as the 2nd Congressional District’s representative in Congress.

Williams went to work modernizing the state’s election system, hardening it against new cybersecurity threats. He worked with Democrats and Republicans on election reforms.

He was a Republican in a state government led by Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper. The partisan divide proved no problem.

“I believe that if I agree with someone 10 percent of the time, I can work with them,” he said.

The state was named America’s “safest place to vote” by The Washington Post under Williams’ watch. Democrats and Republicans praised his programs to encourage turnout and make voting easier.

In 2017, faced with a Trump administration demand to provide voting records to a commission probing allegations of election fraud, Williams fought back. He offered up public documents but denied data deemed private.

He also took on the president’s contention that the 2016 campaign was “rigged” with fraudulent ballots.

“While there are occasional instances of voter fraud, Colorado’s processes are very good at catching attempts to commit voter fraud,” Williams argued.

Trump disbanded the voting probe in early 2018.

But giving up the publicly available records became the top issue for William’s 2018 opponent, Griswold.

“See, last year, at President Trump’s request, our current secretary of state sent all of our personal voter information to Trump’s Commission in D.C.,” Griswold said in the state’s voter guide. “As a result, thousands of Coloradans canceled their voter registration. Thousands. Colorado’s elections were also targeted by Russian cyber attack in 2016.”

Williams did little to counter Griswold’s claims. Instead, he stuck to his usual campaign, upbeat and positive.

Allies pushed Williams to fight back. Send a negative mailer, they urged. Question her experience or her honesty. Williams refused.

“The automatic instinct is to attack people,” Williams said. “Really, no we shouldn’t. You shouldn’t attack people. I have never been particularly persuaded by people calling me names.”

Williams lost by 155,930 votes. He counted each one.

And he’s ending his campaign the way he started it, quoting Lincoln’s inaugural address that sought to heal American politics torn asunder amid the Civil War. Lincoln is the man that made Williams become a Republican, he said.

He can quote it from memory:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”