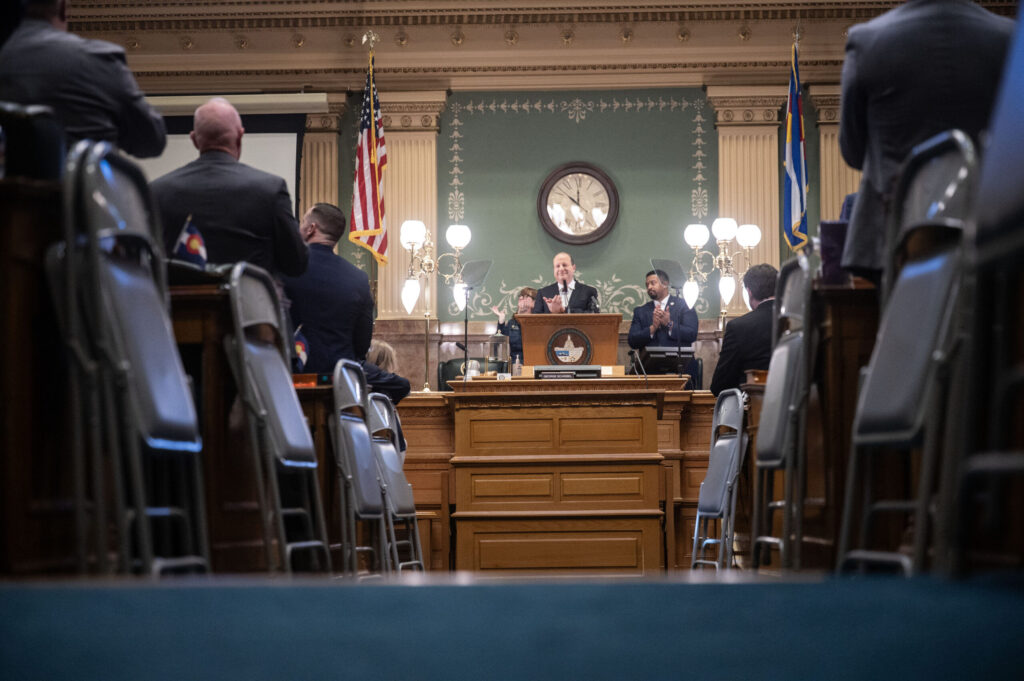

Q&A with Terrance Carroll: ‘Politics shouldn’t be about power for power’s sake’

For a relatively young man who went so far so fast in Colorado politics – and who developed such a high profile by the time he left office – Terrance Carroll has an almost astonishing answer when asked if he ever intends to get back in the ring. You’ll have to read on to find out what he told us, but here’s a hint: When asked for his bucket list, the former Colorado House speaker and Denver Democrat – a practicing attorney at a national law firm, ordained minister and champion of educational choice – says he thinks about writing a book. For at-risk kids.

Terrance Carroll – not what you could call a blindly ambitious political climber. And he’s the subject of today’s Q&A. He discusses the intersection of spiritual faith and hardball politics; his childhood in a poor Washington, D.C., neighborhood; race relations in Colorado; his commitment to education reform – and the pivotal role his mother played in making him who he is. That, and a lot more.

Colorado Politics: You are not only a man of letters – a B.A.; an attorney with a J.D.; a master’s degree in divinity – but you also are a man of the cloth as a Baptist minister. Were there times when you found your work at the Capitol in conflict with your faith? Were or are there times when your faith is in conflict with your party? Do you currently serve a congregation as a member of the clergy?

Terrance Carroll: I found the intersection of faith and politics offers no easy answers to complicated matters of policy. In my opinion, this is especially true if you try to genuinely engage your faith and seek to dig deeper theologically rather than simply using your faith as a weapon. Because I endeavor to honestly to engage with my faith, I always found myself trying to reconcile policy positions with my faith. It was not a matter of party versus faith per se but more of what does it mean to live authentically as a Christian in the public square. Quite honestly, it is not as simple as saying I’m pro-life or an evangelical because I consider myself to be both. However, being pro-life is larger than abortion. It is about the entire circle of life and implementing policies that promote basic human dignity. The conflicts between my faith and my work at the Capitol almost always came into play when I believed proposed legislation was dehumanizing.

I’m currently a member of New Hope Baptist Church. I also guest preach at other churches from time to time.

CP: You grew up in D.C. and came to Colorado as a young adult when you were in graduate school. Did you find race relations different in the West than on the east coast, given different demographics and also, arguably, a different mind-set? What kind of role did race play in your day-to-day work as an elected lawmaker? Did the media make too much of your race and the fact you were the first (and still only) African-American speaker of the Colorado House?

Carroll: At the time, I thought the difference between D.C. and Colorado was what appeared to be the absence of overt racial tensions. However, I soon found there was definitely an undercurrent of racial tension driven by a significant history of racial clashes. I also found the negative stereotypes that some associated with African-Americans were alive and well in Colorado. On a positive note, I discovered the western ethos that caused Horace Greeley to declare, “GO WEST, YOUNG MAN, GO WEST!” provided me many opportunities to forge my own path. I would be lying if I said my race wasn’t one of several lenses through which I viewed my responsibilities as a lawmaker. Each of us brings experiences, perspective and baggage with us when we’re sworn-in as elected officials. This is both a good and bad thing. For me, as an African-American lawmaker, I was always mindful that there were some distinct issues that disproportionately impacted people of color. For example, even in Colorado, where the African-American population is less than 5 percent, African-Americans were and still are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. As an African-American and former police officer, I always felt it was my unique calling to understand the root causes and attempt to address them through legislation. On the other hand, I was cautious not to allow my legislative interests to be limited because of my race. I represented a very diverse district, and my commitment was to represent the entirety of my district without bias or prejudice. Initially, the media did make too much of my race when I became of speaker of the House. This was completely understandable considering the historic nature of my elevation. I also fully embraced and still do my place in history. However, I constantly fought against having my race dominate the substance and status of my position as the speaker. In fact, after a while, I had my staff remove references to me as the first African-American speaker to simply refer to me as the 54th speaker of the House.

Terrance Carroll

CP: You were a big champion of school choice and education reform in the General Assembly. It’s a set of issues that has been known to divide your party. How did you come to be such a vocal advocate of charter schools in particular, and why is there still pushback against charters within some segments of the Democratic spectrum?

Carroll: I remain a champion of education reform and suspect that I always will be. I came to my position on education reform as a result of my life experience. I was born to a single mother and raised in a very poor Washington, D.C., neighborhood. My educational options were very limited. Thankfully, my mother, although a domestic worker lacking a formal education, understood the inherent value of quality education and sacrificed to provide me the educational opportunities I needed to be successful. My commitment to education reform is a direct result of my mother’s sacrifice and advocacy. She not only fought for me but she also fought for every kid in my neighborhood to have access to quality public schools. I do my best to honor my mother through my commitment to ensuring that all our children have the same access to opportunities that I had. Unfortunately, some in the Democratic Party portray advocacy for education reform as anti-public school. That is simply not true. Education reformers are dedicated to improving educational outcomes by expanding access to high quality public schools, whether they be traditional or charter schools.

CP: Life as a member of the bar at a well-regarded Denver law office certainly has its rewards – but it can’t possibly be as exciting, or crazy, as elective office. Do you miss it? And, of course, we have to ask: Do you see yourself getting back in at some point?

Carroll: To be honest I don’t miss it very much. I can count on one hand the times I’ve been in the Capitol since I left office. I don’t anticipate running for office again. I enjoy my life as it is now.

CP: You are still over a year away from the mid-century mark – a relatively young man. What have you not yet accomplished that you’ve always wanted to accomplish?

Carroll: That is hard to say because I have so many interests. This may sound funny, but I would love to write a book targeted toward at-risk kids – as I was labeled – about resilience and grit.

Needless to say my most significant influence was my mother. She would constantly remind me that although we didn’t have much, what little we had (should) be used in the service of others. I watched her worked tirelessly on behalf others throughout her life.

CP: Now that you’ve been out of office a while, looking back, is there anything you’d do differently? Drawing on any added insight – and hindsight – since you left the General Assembly, what’s the first bill you’d carry if you were to suit up again and get back in the game when the 2018 legislature opens this Jan. 10?

Carroll: In retrospect, I would have done more to focus on affordable housing. … (T)here were signs (then) of an impending affordable housing crisis. If I were to suit up again, I’d introduce legislation to allow local governments more flexibility in addressing the affordable housing and workforce housing conundrum this state faces. Colorado’s continued economic vitality depends on a steady supply of affordable workforce housing.

CP: Was there anyone in particular who inspired you in your own career in politics?

Carroll: Needless to say my most significant influence was my mother. She would constantly remind me that although we didn’t have much, what little we had should be used in the service of others. I watched her work tirelessly on behalf others throughout her life. When you think about it, at the end of the day politics shouldn’t be about power for power’s sake. Sadly, politics has become more of a blood sport where blind ideology and the thirst for power have replaced compassion for people. My second inspiration is not a person but an institution, Morehouse College. At Morehouse, we were all taught that a Morehouse Man does not curse the darkness but he lights a candle in the dark to serve as a beacon of hope. I strive to live by the charge Benjamin E. Mays left for Morehouse Men more than half a century ago:

“It will not be sufficient for Morehouse College, for any college, for that matter, to produce clever graduates – but rather honest men, men who can be trusted in public and private life – men who are sensitive to the wrongs, the sufferings, and the injustices of society and who are willing to accept responsibility for correcting (those) ills.”