Colorado state lawmakers chew on state health department over rural water costs

If you think paying for the state’s transportation wishlist at an estimated $9 billion is expensive, you haven’t seen anything yet.

Meet water.

When it was released in 2015, the state water plan estimated the cost to implement its recommendations – just to handle an expected population surge of 3 to 5 million people by 2050 – at $20 billion. That money would handle water-related expenses like new storage or improving the quality of streams and rivers.

But that doesn’t include the cost to replace aging pipelines, storage tanks and water towers, wastewater treatment plants, and other water infrastructure. According to the state’s public health agency, there are 442 projects awaiting funding for wastewater treatment at a cost of $7.3 billion, and another 334 projects for drinking water, which brings the total to $15 billion.

This week, Mike Brod, executive director of the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority, pointed out that $15 billion is not included in the water plan. The authority is a quasi-governmental agency that provides low-cost financing to local governments for drinking water and wastewater treatment projects.

And while a survey of water utilities and municipalities was designed to forecast that cost over 20 years, Brod told lawmakers this week the $15 billion is what’s needed in the next five years.

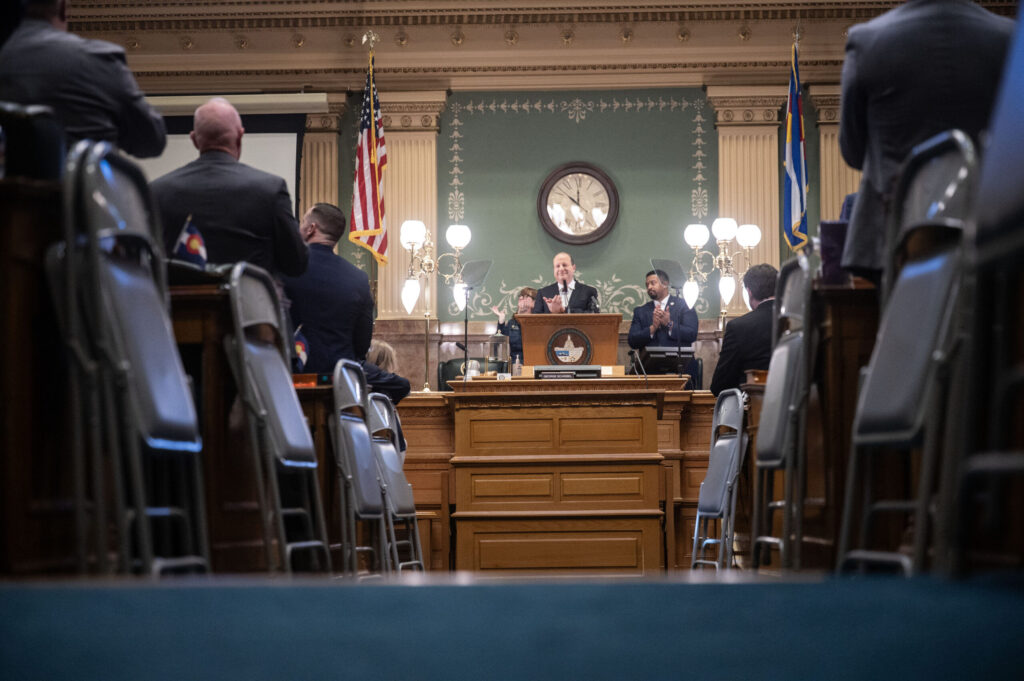

During the last two years, lawmakers have authorized several pots of money for implementing the state water plan, and they’ve also signed off on funding for water infrastructure. Brod, who this week spoke to the General Assembly’s interim water resources review committee, said the authority makes loans to 15 to 18 drinking water projects per year and about the same number on wastewater treatment projects, with loans at around $100 million per year. About $25 million comes from the feds; other dollars come from local severance taxes.

Most of those projects are for water systems in small communities, he said.

But that didn’t satisfy some of the members of the water committee, who are hearing complaints from some of their smallest communities that they’re being hit with requirements to upgrade water systems without any evidence that water quality is in jeopardy.

Take Peetz, population 239. Last month, Logan County commissioners, including Joe McBride, heard from residents of Peetz and several other small towns that they simply cannot afford the millions it would take to upgrade their drinking or wastewater systems.

Peetz doesn’t have the kinds of businesses that generate sales tax, so its town budget relies mostly on utility and property taxes, to the tune of about $200,000 per year.

Last year, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment implemented new regulations that require many small towns to upgrade their drinking water systems. For Peetz, that cost is estimated at $2 million.

“How are these small towns going to be able to afford that?” McBride asked. “I’m all for good water, it’s essential, but there’s not much thought on how realistic” the requirements are to upgrade are for these small towns. And while water is the top issue in the county, McBride said, the new regulations were “dumped on the towns all at once without warning.”

Peetz doesn’t have a wastewater treatment system; McBride told Colorado Politics most people are on well water with their own septic systems. But it does have sewage lagoons, and CDPHE is on their case about leakage from those lagoons into groundwater supplies. According to Logan County commission meeting minutes from August, Peetz town officials did not find any seepage in the town’s wells, and they reported none of the wells were contaminated. The only problem found was about three feet from the lagoons.

Even if Peetz or some of the other small towns facing these requirements could afford to upgrade their systems, town budgets have issues other than water, like fixing roads, McBride said. “It would cripple the budget to do anything else.”

Pat Pfaltzgraff, executive director of the water quality control division at CDPHE, told lawmakers that the new regulations came down from the Environmental Protection Agency, and that state law requires the division implement those regulations.

Sen. Jerry Sonnenberg of nearby Sterling, who chairs the interim water committee, told Pfaltzgraff that the small towns in his district simply can’t afford to redo their water systems.

“We want to work with them” on these issues, Pfaltzgraff replied.

“Our last resort” is to take them to an enforcement action, he said.

It’s not just a problem in northeastern Colorado. Tyson Ingels, the lead drinking water engineering for CDPHE, noted that water infrastructure is aging around the state, with some water towers constructed more than 100 years ago. And their age is showing.

Ingels said older drinking water distributions systems were constructed of asbestos cement, wood pipes or cast iron. He warned that a catastrophic replacement for these systems would be beyond what a town can afford and pointed to an incident in Alamosa just ten years ago, when salmonella got into the drinking water supply. As many as 1,300 people may have gotten sick from the contaminated water, and one died, according to a CDPHE report.

The likely cause was fecal contamination from animals that got into the city’s Weber Reservoir, the primary water well for the city. The report said the reservoir had several small cracks and holes that likely allowed the contamination in and that those breaches had existed for a long time.

Between 2010 and 2014, Ingels told the committee, state inspectors found more than 400 storage tanks that had “unacceptable” open paths to contamination, either from animal feces, runoff, bird droppings or open holes in the tanks. The state inspects those water systems every three years, he added. “We’re finding more things wrong.”

But Sonnenberg and fellow Sen. Randy Baumgardner of Hot Sulphur Springs both raised questions as to why towns have so little time from the CDPHE to make these changes.

“Rural communities are up in arms,” Sonnenberg said. “The water quality hasn’t changed, but (these towns are being) told their systems aren’t good enough any more.”

And what if a town doesn’t have the money? Baumgardner asked. How much time do they get?

Pfaltzgraff said his agency is trying to work collaboratively to find grant money whenever possible. “When there’s a small community that needs to improve infrastructure, we’ll bend over backwards working with them to extend out the compliance period. However, if you have an acute risk to human health, we will be more aggressive. Ultimately we will try to find the money.”

The problem is likely to become greater with the expected surge in the state population, Pfaltzgraff said, both from the drinking water side as well as the wastewater treatment issues that will come with another three million people or more in the next 32 years.

Sonnenberg told Colorado Politics this week that he wasn’t satisfied with the answers he got from CDPHE and believes the agency can be a little more flexible on the wastewater treatment upgrades.

“There’s probably a couple of solutions. We could run a bill” that says that EPA has standards and that the state cannot exceed them, for example, he aid.

The bigger issue, he said, is that “a government entity is coming in, not changing the quality of water, but mandating that communities spend money they don’t have.”

The communities ought to be driving those changes, he said, and if there’s a problem with their water quality, they’ll deal with it.