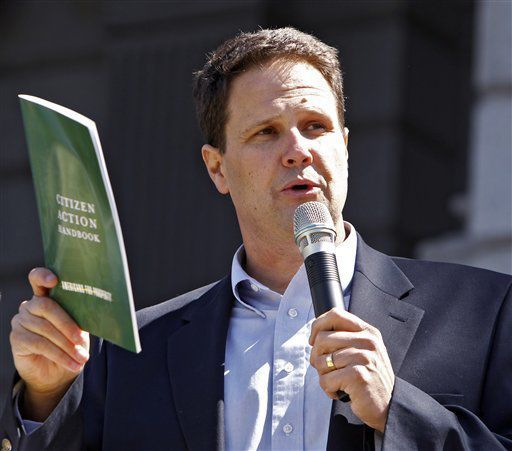

Political veteran Dick Wadhams outlines ‘redprint’ for Republican victory in Colorado elections

Dick Wadhams, who chaired the state Republican Party for two terms and had a hand in electing the statewide officials who set the tone for the Colorado GOP across three decades, has a message for the party: Republicans have never had it easy in Colorado.

“This has always been a competitive state; this has never been a Republican bastion,” he told the monthly meeting of the Highlands Ranch Republicans early last Friday morning.

“When a Republican wins election in Colorado,” Wadhams said, “it’s a game of inches.”

That’s been true as long as nearly anyone listening to Wadhams while eating breakfast at Salsa Brava restaurant can remember, even though GOP candidates had a solid run for a while starting near the end of the last century and gave Colorado’s electoral votes to Republicans nine out of 10 elections from the mid 1960s through George W. Bush’s pair of wins.

But in the modern era – Wadhams pegged it at roughly the last five or six decades – Republicans have only elected two governors, who have served three terms since 1970, while twice as many Democrats have held the mansion for nine terms. The parties have sent about an equal number of senators to Washington during that time, and the once-reliable presidential vote has flipped, with Democrats taking all three of the last three elections.

Wadhams made it clear, however, that Republicans have no reason to despair, because there’s a tried-and-true method to getting what he described as principled, conservative candidates across the finish line. He calls it the “redprint,” and that was what he wanted to talk to the Douglas County Republicans about. (The phrase is a play on the famous “Blueprint” a group of wealthy Colorado Democrats designed to take control of the Legislature and build party infrastructure in the early part of the last decade.)

Set in a national context, where political prognosticators from across the spectrum are still reeling from and adjusting to President Donald Trump’s upset win, Colorado stands as a beacon of stability, and that holds some lessons for the road ahead, he said.

“Democratic pollsters are still trying to come to grips with how they missed those white working class voters,” Wadhams noted, pointing to Clinton’s collapse across the industrial midwest and neighboring regions, losing in Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio and other formerly solid Democratic states.

“Here in Colorado, the polls were right,” he said. “The polls showed Hillary Clinton was going to win by 5 and she did.” At the same time, incumbent Democrat Michael Bennet won reelection to the U.S. Senate by a similar margin over Republican nominee Darryl Glenn, although polls had showed him doing slightly better before Election Day.

“Why did they win, and why did Heidi Ganahl, the only Republican to win statewide?” he asked, naming the University of Colorado regent, the relative bright spot on an otherwise dim election night in Colorado for Republicans. (While no congressional seats changed hands, the GOP kept its one-seat majority in the state Senate, lost a few seats in the House and gave up control of the State Board of Education to Democrats for the first time in a generation.)

In Colorado, Wadhams said, it was the Access Hollywood tape that turned the tide for Trump and helped stem whatever conservative tide might have lifted other candidates.

“You could almost feel the suburban voters turning away,” he said with a grim shake of his head, recalling the days about a month before the election when the landscape was overtaken by an audiotape of Trump boasting that he could have his way with women because he was a celebrity. “‘We can’t vote for Donald Trump – we don’t like Hillary, but this is too much,'” Wadhams said was the palpable reaction among the state’s swing voters.

“Every poll before Access Hollywood showed Trump was in a position to win Colorado. The bottom fell out after that,” he said, pointing to women in the suburbs around Denver, including in Jefferson and Arapahoe counties, as well as Douglas County, where Trump won but didn’t perform as well as he should have.

The Senate seat was the other big loss for Colorado Republicans on election night, particularly stinging after Cory Gardner unseated Democrat Mark Udall two years earlier, appearing to set the stage for statewide GOP candidates for years to come.

“I’m not here to beat up on Darryl Glenn,” Wadhams said. “He’s a good man. You cannot help but be inspired by his personal story. … But this is the brutal truth. We learned once again, and we learn it time after time in this state, you cannot run from an ideological perspective and win.”

(Wadhams reminded the audience at another point in his remarks that he managed the campaign of one of Glenn’s Republican opponents, former CSU athletic director Jack Graham, who ran second in the five-candidate primary.)

“Darryl Glenn lost a race he should have won. Michael Bennet was very unpopular – every poll showed him under 50 percent, and he had very high negatives. His campaign never had good numbers,” Wadhams said.

And the reason, Wadhams said, that Glenn lost – in Colorado’s game of inches – is that he led with calling himself “an unapologetic Christian conservative pro-life Republican.”

“Does that mean we cannot elect a conservative, pro-life Republican?” Wadhams asked. “Absolutely not.”

He said he had three names to prove his point, and they all happen to be Republicans whose campaigns he managed to statewide wins during the GOP’s heyday in Colorado: former Gov. Bill Owens and former U.S. Sens. Wayne Allard and Bill Armstrong. (Along with Hank Brown, who held Armstrong’s seat for a term before Allard won it after Brown retired, and former U.S. Sen. Ben Campbell, who won reelection as a Republican after switching parties a couple of years into his first term, that would be all the Republicans elected senator or governor in Colorado during the four decades between the early 1970s and Gardner’s win in 2014.)

What did those three candidates share, other than a campaign manager and the ability of each to win statewide two times?

“They didn’t lead with an ideological preference,” Wadhams said. They all presented – and advanced – what he called a mainstream conservative agenda, managing to appeal to “that mass middle of unaffiliated voters, especially in the Denver suburbs” in the process.

While Gardner’s victory yields some lessons, Wadhams pointed out, “as admirable as his campaign was,” he didn’t have to navigate a primary, so there’s less to glean from his experience.

Owens, coming off two terms as state treasurer, faced a competitive primary with Tom Norton, the Senate president from Greeley, and, even though he’d been elected statewide twice already, started out behind in the polling.

“We started off that campaign with a very clear agenda – to improve transportation, cut taxes and reform education,” Wadhams said. “The day he announced, he did not announce he was an unapologetic constitutional conservative. He did not lock himself into a narrow ideological agenda during the primary.”

Smiling, Wadhams added, “My goal as his campaign manager was to win a general election. What’s hard to do is to win a Republican nomination in Colorado – and win a general election.”

When Owens ran his first successful campaign for governor in 1998, both he and Wadhams could look to another campaign Wadhams had run just two years earlier.

Allard, at the time a representative of the 4th Congressional District, also started his competitive, crowded primary a ways back in the polls. When he announced his Senate run, Wadhams recalled, his chief issues were balancing the federal budget and reducing taxes and regulations.

“Those are the two candidates Republicans can learn from,” Wadhams said. “They also need to look at Darryl Glenn and figure out how not to win in Colorado.”

“He’s a good man,” Wadhams said again and listed some of Glenn’s distinctions and triumphs, including his service in the Air Force and career in Colorado Springs and El Paso County politics, and then added, “I am not saying a conservative, pro-life Republican cannot win in Colorado, even though this is a pro-choice state. But we’ve got to think long and hard about this, ladies and gentlemen. That last three points is awfully tough to get in this state. You win in Colorado by inches.”

Glenn secured the top spot on the primary ballot when he shut out the other candidates at the state GOP assembly in Colorado Springs almost exactly a year ago, in part on the strength of a barn-burner of a nomination speech, but he’d also been traveling the state for a long time before that, Wadhams noted.

“Darryl Glenn, to his credit, he campaigned for two years and gave a powerful speech. I was on my feet cheering. But I also thought, ‘He is really locking himself into this ideological position.'”

Then, after four more candidates qualified for the primary ballot by petition – including Graham, whose campaign Wadhams managed – Glenn kept running hard. As the June primary neared, he wound up with the financial backing of the Senate Conservatives Fund, bolstering what had been a shoestring campaign.

“Darryl Glenn got 37 percent of the vote. That is the rock-hard conservative base in a Republican primary,” Wadhams said. Then, shaking his head, he added, “He came out of the primary, and he basically continued to campaign in the primary. He went to Republican groups, he didn’t want to debate Bennet – it was basically a bad situation.”

Turning his attention to next year’s gubernatorial race, Wadhams stressed that the stakes are high. Republicans, he added, are in danger of losing the governor’s office for the fourth time in a row and could face dire consequences as a party.

“It is the most important office in the state,” Wadhams said. “When Bill Owens was governor, we passed a $1.7 billion transportation plan without raising taxes – we expanded I-25, and did 26 other projects around the state.” The ability to put those kind of changes into effect – as well as the kind of constant presence a governor has in the lives of Coloradans – is unparalleled.

“We need a Republican governor to build the Republican Party around. I love Cory Gardner, but the truth is, U.S. senators don’t have the ability to do that. The most important office we need to win in 2018 is the governor’s office. We have suffered as a party by only winning that once in the last 40 years,” Wadhams said. “It all starts with the governor’s office.”

One reason, he noted, was that the next governor – Democrat John Hickenlooper is term-limited – will make appointments to the state’s reapportionment commission, which draws legislative boundaries, and will have a say in the congressional lines the Legislature is supposed to formulate. Because there’s a good chance Colorado will wind up with an eighth congressional seat after the 2020 Census, he added, the districts could change dramatically, making it even more important to have a strong voice leading the conversation.

In addition, the next governor is likely to get two or three appointments to the Colorado Supreme Court, which has been filled mostly by Democrats over the last four decades.

“This governor’s election probably has more at stake than we generally have,” Wadhams summed up. “Cory’s election in 2014 – if we had lost that Senate race, I think we would be a blue state now. But if we elect another Democratic governor, the third governor for the fourth election, it really could be the nudge for us to finally go blue. I’m not underestimating secretary of state, treasurer, all these other officers, but the governor’s race is the only race that matters in 2018.”

While the state GOP hadn’t yet chosen its party officers at press time, Wadhams said after he delivered his remarks that Republicans should keep in mind that candidates matter far more than state chairs.

“Regardless of who we elect and regardless of how good a job they do getting Republicans out to vote,” Wadhams told The Colorado Statesman, “it really doesn’t make a difference if we have a candidate who offends those unaffiliated voters. People need to understand the role of the state chairman is very important, but it only goes so far. The state chairman cannot single-handedly elect anybody to anything, especially at the state level. We’ve got to have candidates who run effective campaigns.”