If not now, when? Presidential election reform proposal killed in Colorado, again

Colorado Senate Republicans on Wednesday voted down a proposal to join the National Popular Vote Agreement, which would require Colorado to deliver all of its electoral college votes to the presidential candidate who wins the popular vote tallied from all 50 states.

Ten states and the District of Columbia have already signed on to the agreement, representing a total of 165 electoral college votes. The agreement would take effect only once states party to the agreement can deliver a majority of electoral college votes – the magic number 270.

Depending on your perspective, 2017 is a year ripe for signing onto the proposal.

Presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump spent the bulk of the many many months of the campaign in roughly eight swing states. They met with a very small percentage of the country’s citizens. They avoided many states – and with good reason. What possible strategic advantage could Clinton have gained by spending time and money visiting deep red Wyoming? The only strategic reason Trump visited California was to raise money.

There’s also the fact that Trump won the election despite losing the popular vote by some 3 million, the largest number lost by far by any presidential election victor. If there’s a historic quality to his election, that’s at the top of the list. Trump’s steep loss in the popular vote cuts into his legitimacy as president, as would such a loss do for any other candidate.

But not everyone is swayed by that set of facts.

Suzanne Staiert, deputy secretary of state, called the National Popular Vote Agreement “bad public policy.” She said it would bind Colorado election results to states that have less “clean and secure” voter rolls, looser or more restrictive election administration systems, and different voter-eligibility standards. Felons can vote in other states, she pointed out. That’s not the case in Colorado.

Sen. Kent Lambert, R-Colorado Springs, argued that the advantageous effects of the electoral college were being ignored in debate. He cited Democratic New York U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan as his go-to persuasive source on the issue.

“The electoral college has been used as an institution to define majorities, and the parties that emerged as a result,” argued Moynihan in a 1979 Senate floor speech, “had as their single most characteristic quality that they were not ideological, that they were not sectional nor confessional, and never, in the two great parties, extreme.

U.S. political parties, he continued, are forced by the electoral college system to resort to “obtaining consensus, retaining a structure of concurrent majorities around the nation that makes it possible to win a majority of the votes and in the electoral college, and, thereafter, to govern with the legitimacy that has come of attaining to such diverse majorities.”

The speech is powerful, even if it rings now with the sound of a different era.

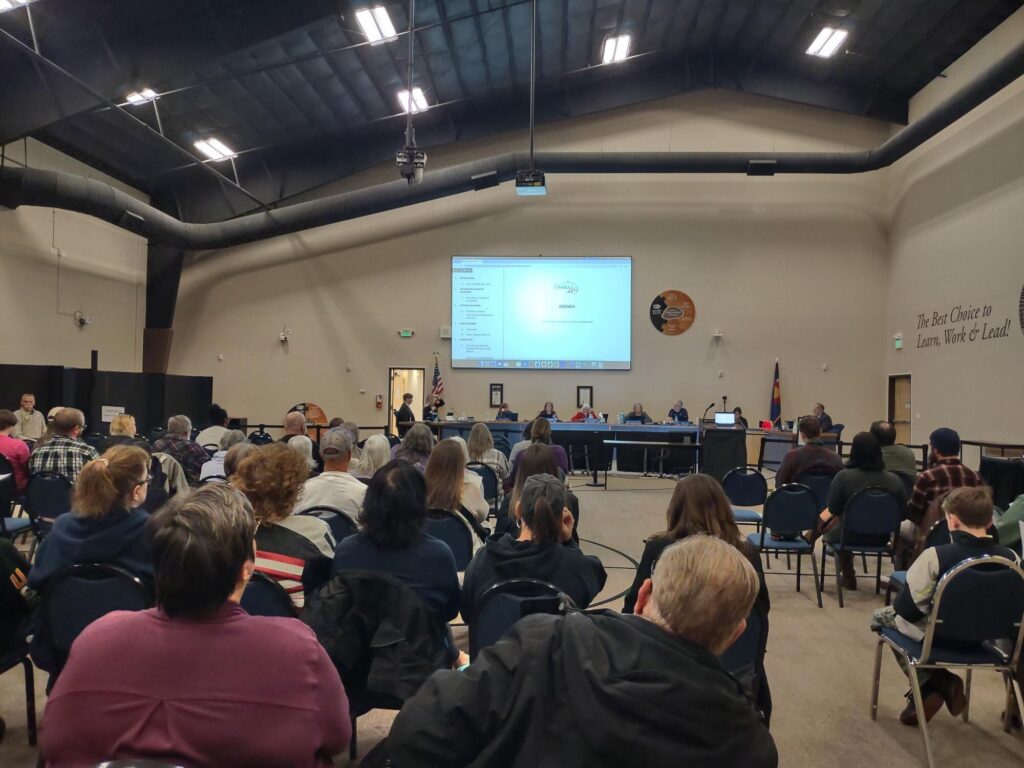

The hearing for the Colorado bill stretched over hours. It included testimony from people speaking from remote parts of the state through occasionally spotty digital networks.

Robert Britton spoke from Grand Junction. He seemed pained by the current system.

“In this past election, we’re talking about 3 million people whose votes were thrown away, people who took the trouble to inform themselves and to cast their ballots on election night, and it was all lost.”

Wyatt Hurt, a Grand Junction high school student and Democratic Party activist, said the electoral college system has a deleterious effect on youth politics. Young people don’t think their votes count, he said, agreeing with a long list of witnesses that said that the system worked to suppress voter participation.

“What Democrat in blood-red Wyoming and what Republican in sky-blue California could be legitimately convinced to believe their vote for president matters at all?” It was a question asked in variations time and again.

Brandon Kline, a Denver lawyer, noted that there are more Republicans who cast votes in blue states like New York, California and Illinois than there are Republicans who cast votes in many red states combined. Those blue state Republican votes are all stranded in the current system.

Witnesses argued that the electoral college gives more weight to votes cast in low-population states, which feels not completely democratic.

“The presidential election is the only one in the nation that fails to respect the democratic principle of one person, one vote,” said former Democratic state lawmaker Polly Baca, who was also voted a Colorado member of the electoral college last year. She became one of the so-called Hamilton electors, who argued for the freedom to vote how they wanted and not be bound to state vote totals. It was an effort to elect a Republican alternative to Trump.

“If the electoral college is not a deliberative body, then there’s no reason for it,” she said.

Testimony took hours but, when it came time to vote, it was over in a flash. Senate Bill 99, sponsored by Sen. Andy Kerr, a Lakewood Democrat, was voted down by the Senate judiciary committee on a 3-2 party-line vote.

Kerr noted that, as a House lawmaker, he sponsored the same bill in 2009, after Barack Obama won the presidency in a landslide.

“This shouldn’t be partisan. This isn’t about party politics,” Kerr said. “In some years my candidate wins. In other years they lose. In all years, our votes should count equally. Let’s honor red voters in blue states and blue voters in red states. At the end of the day, the process should count every vote equally.”