It’s all about education for longtime lobbyist Jane Urschel

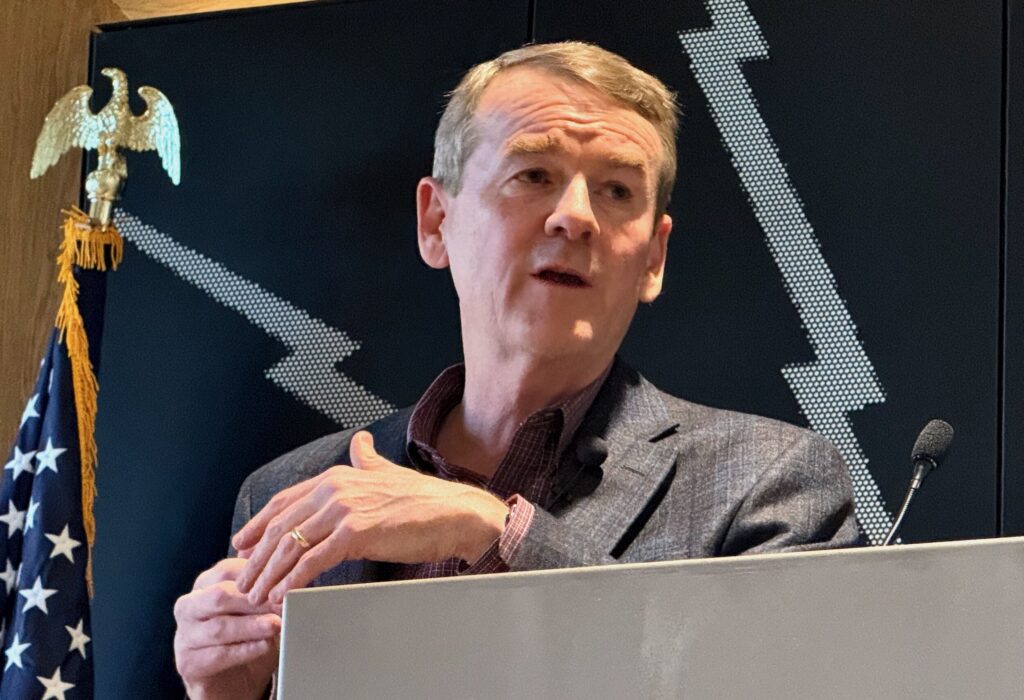

Even after 23 years lobbying at the state Capitol, Jane Urschel says she learns something new all the time.

“Every day is different,” she says. “There’s no continuity – you just go down there and find out what the surprise is for the day, then you deal with that.”

Urschel is in charge of advocacy – not just lobbying, though that’s a big chunk of it – for the state’s school boards, serving as deputy executive director of the Colorado Association of School Boards, known as CASB.

She started visiting the Capitol regularly when she was a lobbyist for the state PTA in 1988. The next year Urschel won election to the Jefferson County Board of Education, became the board’s president and soon began spending even more time visiting lawmakers. After her husband asked, “How much longer are we going to keep supporting your charity?” she decided against running for a second term, she recalls with a smile, and was offered a job lobbying with CASB. She was named to her current position the next year, and she hasn’t looked back.

“I was there before term limits, I was there before you couldn’t smoke in the Capitol,” she said during a recent interview with The Colorado Statesman in the association’s office building, just two blocks south of the Capitol. “I’ll have to tell you about that,” she said with a mischievous smile. But first she wanted to make sure it was clear what her job entails.

“I think a lobbyist is someone you hire to protect yourself from someone you elect,” she says. It has the feel of a well-worn line, but it doesn’t sound remotely automatic or rote. Urschel, who earned a doctorate in Educational Leadership and Policy Innovation at CU Denver – she wrote her dissertation on the touchy subject of local control for schools – takes self-government and her role in it seriously.

“It’s the First Amendment right of someone who hires a lobbyist. School boards cannot be down at the Capitol every day, and that’s true of a bunch of different constituencies,” she says. “Lobbying sometimes gets a bad name, but it is the fulfillment of First Amendment rights for a lot of people.”

In Urschel’s decades lobbying legislators, there’s been one constant.

“The most important thing for us is local control,” she says, noting that when she studied the topic she interviewed lawmakers and found “very conditional” support for the principle, which is enshrined in the state constitution in a section that says local elected boards have control over instruction. Sometimes legislators said they’d be willing to grant more local control if a district allowed enough charter schools to operate, sometimes if the schools did better in assessments. But it was rare to find a lawmaker who agreed with the school boards that the state mostly ought to stay out of the classroom.

“Things have really changed around local control,” Urschel says. “If we don’t bring it up, it doesn’t even come up. We have a generation of legislators who aren’t very aware about what local control is.”

Another topic that Colorado legislators don’t know much about anymore is how to make tax policy, she says, shaking her head.

“We are the only state legislature in the nation that cannot make tax policy, because our tax code is in our constitution – TABOR, Gallagher and (Amendment) 23,” she says, ticking off the constitutional components Gov. John Hickenlooper has called “the fiscal thicket.”

In the more than two decades she’s been paid to lobby lawmakers, the Capitol has undergone some big changes – some mostly cosmetic, others with a powerful effect on how things operate under the dome.

Urschel remembers the days when a blue haze floated throughout the hallways, before smoking was banned from the building, and chuckles at a story about the late state Sen. Al Meikeljohn, the powerful Arvada Republican who served 20 years in the chamber.

A former member of the Jeffco school board, he chaired the Senate Education Committee and scheduled meetings to start right before lunch. “Sen. Meikeljohn would rock back on two legs of the chair’s chair,” Urschel smiles, “and he would listen to testimony, and then his face would get red and he would slam that chair back on all fours – ‘Colleagues, it is time to vote!’ – which meant, ‘I need a smoke!’ We always finished before lunch so Sen. Meikeljohn could get out in the hallway and have a smoke.”

And Colorado’s is no longer a rural legislature, Urschel notes, counting fewer and fewer rural residents among lawmakers.

That point was driven home, she recalls, when a school board from Alamosa came calling on lawmakers – school boards visit the Capitol every Wednesday – and members told Urschel how “disenfranchised” they feel. “They feel like it’s not local control anymore, it’s Denver control.”

The days of lawmakers lingering at the Capitol and in the surrounding neighborhood until all hours – at least before the crush at end of session – have also waned. “Everybody goes home – even if you’re here from a rural area, you’ve probably rented a place out in Jefferson County or somewhere, and you’re going to go home. You’re not going to hang around and have dinner and have a drink. So, in some ways that’s easier on lobbyists, but in other ways, we don’t get to build the trusting relationships the same way,” she says.

“Amendment 41 has put kind of a kibosh on that,” Urschel says, referencing the voter-approved government ethics measure that includes a ban on lobbyists giving legislators anything of value, including lunch or a drink.

“It’s things like that that impede relationship-building, and lobbying is all about relationship-building,” she says with a shake of her head.

The advent of term limits is another change, and Urschel is not a fan.

“I’m not a believer in term limits,” she says. “We have made experience unconstitutional in Colorado. James Madison said the legislature is a school, and the cream should rise to the top and educate the rest. We don’t have that. By the time they get the experience and they become real leaders, they go out the door. I think it’s unfortunate. We pay a big price for that.”

One results, she says, is that “the lobby corps far outlasts the law-making corps, if you will. We have some great leaders – I’m not suggesting we don’t – but leaders could always use more experience.”

It makes lobbyists even more crucial, she contends.

“The role of a lobbyist is to educate. In fact, I think we become – again, what James Madison said, that legislators should become subject-matter experts. I think that’s true of lobbyists. People should be able to go to them and feel they’re getting good information and feel they can trust that.”

That principle, she says, is behind one of the firmest rules for lobbyists.

“If you do anything with a legislator to violate their trust in you, that’s a very bad thing,” she says. “That’s something I’ve done a few times without realizing it. You get information and you want to share it – that’s the way lobbyists are, because you want something in return for that. I can remember a couple of times when I said something I shouldn’t have to people I shouldn’t have. And the first thing you do is, you go and apologize. Admit it, don’t deny it. You have to build those relationships.”

She cautions against lobbyists getting hardened or cynical.

“There are a lot of my colleagues who, I think, don’t respect legislators, and I do respect them,” Urschel says. “Like Churchill said, this is the worst form of government, except for all the rest. We do have the best form of government in the world, and I will do everything I can to defend it and those who serve in it. I don’t make jokes about legislators, and I don’t call them bad names behind their backs. If you’re talking about them behind their back in a negative way, that’s going to come through.”

And the reason she works to establish and maintain good relationships, she points out, is to advocate for school boards, always pressing for “that defining line between what the state should control and what school boards should control.” Lately, she sighs, boards have been “over-ridden” by a state government anxious to control education.

“The state has taken to dictating curriculum. In the amount of testing. In nutrition bills, where they and the federal government want to tell us what to serve – they are the cooks in the kitchen. They want to tell us what to teach, they want to tell us how to teach. It’s very intrusive,” she says curtly.

“We have to cater to all kinds of groups, from the five-member school board down in the San Luis Valley, which has completely different issues than the Jeffco School Board,” says Matt Cook, a former Aurora Public Schools board member and one-time president of CASB, who started last fall as director of public policy and advocacy for the association.

Although he counted himself as fairly involved politically, Cook shakes his head and smiles as he recalls what a steep learning curve he’d encountered working at the Capitol.

“It looks like it curves straight up,” he marveled. “I thought I had a good grasp of how things work, but it’s a whole other world when you get down there and find out that’s how they get things done. It’s like learning another language.”

One of the biggest eye-openers, he said, was just how powerful the Joint Budget Committee was, even though that adjective is nearly always used in conjunction with the six-member legislative body.

“I didn’t realize how much folks defer to them – and rightly so, they are the experts on a lot of things,” he says. “We have some disagreements with them, but one of the things is, with so many new folks here, they do defer to the folks who have some knowledge.”

Urschel and Cook have spent plenty of time lobbying JBC members, partly in an attempt to correct the so-called negative factor, a nearly $5 billion deficit owed schools since the state began tightening its belt in the last decade.

Urschel recalls that CASB and other education organizations had “a great victory” two years ago, although since then, when Republicans and Democrats split control of the chambers, she says school funding advocates have “hit a bipartisan wall.”

But she still savors the wins of 2014.

“I think they thought we would do what people always do, which is to say, ‘Oh, that’s all we’re getting? We understand, times are hard.'” Urschel says. “But we stood up two years ago and said, ‘No, that is your problem, you have a debt to pay.'”

There are more organizations with an interest in education at the Capitol than when she started lobbying – “Our job is finding allies,” Urschel says unequivocally – but they often don’t agree about everything. Still, she suggests looking for the big group “clustered together, usually on the second floor,” and says that will be the modern incarnation of the “Lobby Corps,” an appellation for education advocates that’s been around for decades.

The Lobby Corps used to just be the Colorado Association of School Executives and the Colorado Education Association, along with CASB and the PTA, but has swollen over the years to also include Democrats for Education Reform, groups representing charter schools, lobbyists retained by larger school districts and others. Because it represents local elected entities, CASB also works closely with the Colorado Municipal League, Colorado Counties, Inc., and the Special District Association of Colorado.

“So much of what lawmakers do is codified in the constitution,” Cook observes. “Education is something where lawmakers can have an influence.”

That codification would be the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, the Gallagher Amendment and Amendment 23, measures that guide how the state can raise and spend its funds. Urschel says it’s time to untangle the thicket.

“We need to modernize TABOR,” she states flatly. “Polling has found that people don’t like it when you talk TABOR down, because it makes them feel bad – even though most of them weren’t here when it passed, we’re not questioning their judgment – but when you bring up the conversation about modernizing, they like that. The thing is, people don’t understand what TABOR does, or Gallagher, or Amendment 23.”

It isn’t just TABOR – CASB has played a big role in the Building a Better Colorado attempts to come up with proposals to unwind some of the effects of the amendment – but also Amendment 23, which mandates a level of state spending on education.

“We want to see 23 go,” she says. “CASB supported it because it addressed some inequities. But those things should not go in the constitution, and we now know that. They should, all three of them, they should go. We believe that.”

Then, leaning back, Urschel nods out the window. “I think we are becoming a system of laws without government – that’s what Colorado is becoming. We don’t want that.”

– ernest@coloradostatesman.com