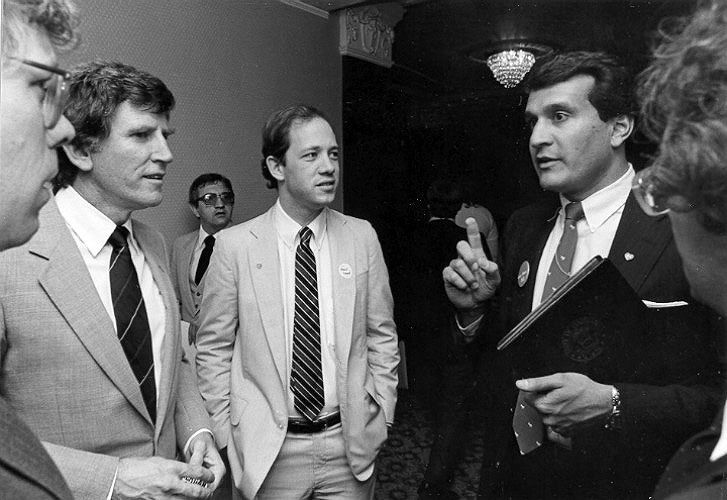

Sunday Special Report: Former staffers recall ’84 run of Gary Hart

It doesn’t take all that long for anyone who knew Gary Hart back in the 1980s to utter some semblance of the same old phrase.

He came so close to winning.

Indeed, in the minds of many, Gary Hart is the subjunctive president, the man who should have been.

Much has been made of Hart’s fall from grace. The alleged Donna Rice affair and Monkey Business don’t need yet another account. But what is worth looking back at, what is worth remembering, is how a rugged U.S. senator from Colorado rose from relative obscurity to upset the political establishment in the 1984 election.

With the first electoral contests of the 2016 cycle just weeks away, former Hart staffers, longtime companions and friends recounted in a series of interviews with The Colorado Statesman how they pulled off an unlikely second-place finish in the ‘84 Iowa caucuses, what made that campaign so special, and how it came to be regarded as a role model for political insurgency.

“I don’t think there was ever a colder place in my life than Des Moines, Iowa, in the winter of ’83-’84,” says Jep Seman, a member of Hart’s campaign team in the early caucus state back then. “Denver, by comparison, is the banana belt.” He chuckles as he thinks back to the grim Hawkeye winter. These days, Seman roams the halls of Colorado’s Capitol, lobbying for oil and gas interests as founder and president of the Corporate Advocates firm.

But back then, he was part of a local crew that didn’t care too much about conventional election wisdom. Strapped for cash, the Hart campaign had employed young, inexperienced, idealistic staffers across the board. They slept in bathtubs and on floors, sometimes deferring their pay for months. In return, they got to take their youthful enthusiasm and homemade creativity out on the trail to fight the party machine.

And so it happened that during an annual agricultural convention in Ames, Iowa, “sometime in early January,” Seman remembers, Gary Hart — a farm-boy-turned-senator originally from rural Kansas — rolled through town atop a giant John Deere tractor. The traveling press corps, understandably, went wild.

“He wasn`t unfamiliar with tractors,” Seman says. “But as I am sure you can appreciate, tractors in that day and age were as big as buildings, and we were all a little nervous that he was going to run over a reporter or a supporter.”

Luckily, no harm was done. Hart, though, was the talk of the town before he even delivered one of his marquee policy-laden and oratorically honed speeches at the actual meeting. It was that kind of speech, Seman believes, that helped Hart capture the hearts and minds of enough Iowans to eventually propel him to a surprising second-place finish in the caucus.

“He put a real emphasis on saving family and small farms and not letting all of the Midwest — what we referred to then as the nation`s breadbasket — morph into corporate ownership,” Seman says. “Hart had always been very involved here in Colorado on soil conservation issues and water and energy policy, all those things that really mattered to farmers.”

Laurie Hirschfeld-Zeller was another young aide who was dispatched from Hart’s D.C. Senate office to the grueling Iowa winter — in her case, the northwestern part of the state around Sioux City.

At the time, a meatpacking factory in the region went on strike, supported by its powerful union. Most of the unions, then an unquestioned institutional force within traditional Democratic politics, were backing the frontrunner, former Vice President Walter Mondale. Hirschfeld-Zeller scrambled to recruit volunteers.

“A lot of the Democrats that were out of work and available to volunteer were Mondale supporters, and they were all angry — as they should be, they were in a rough place,” she remembers. “It was a cold, long winter.”

Yet, eventually, she succeeded.

“If you could get a little bit of time to get people outside of their label, whether they were a union member or a meatpacker or a teacher, that’s what broke the logjam,” says Hirschfeld-Zeller. “It wasn’t just a labor issue. It was also an issue of traditional Democratic Party alliances versus people who wanted to be part of a bigger concept of what a Democratic president could be like.”

A bigger concept. Something new. Change. Or, as senior Hart campaign operative Mike Stratton puts it, “a breath of fresh air to the old style of politics. He had fresh ideas. He took on the establishment.”

Hart challenged the military-industrial complex and argued for a meaner and leaner military force — both on land and at sea. He foresaw that conflicts would shift from territorial disputes to fights against stateless groups. He was a champion for veterans. He fought to preserve the environment. Barry Goldwater, an iconic conservative of the time, said that, despite all topical disagreements, he had never met a more principled politician.

And yet, Gary Hart never became president — or even the Democratic nominee.

Stratton was Hart’s student coordinator at Colorado State University in 1974. Ten years later, he helped orchestrate a presidential primary campaign that fell short only after exactly the traditional alliances that the Hart team so despised helped Mondale lock down the nomination. (Stratton went on to attain certified guru status among political consultants and is a principle at Stratton-Carpenter Associates.)

A vast majority of the newly introduced “super delegates” — party officials not bound by their state’s primary vote — came through on the convention floor for the frontrunner. Hart’s insurgency, fueled by the momentum of a surprisingly strong runner-up finish in Iowa and a stunning win in New Hampshire shortly after, had come to an abrupt halt.

“The Democrats were in search of change, and we almost upset Vice President Mondale,” Stratton says. “And, obviously, the country was in search of change, so they elected Reagan.” (President Ronald Reagan clobbered Mondale in the November election, carrying 49 states.)

There it was again, subtle. What if? What if Hart had been the nominee? He came so close.

“I guess you might say the party, by a relatively small margin, turned to someone who it felt it owed something to,” ponders Thomas Hoog, a close Hart confidante and his former Senate chief of staff.

Rick Ridder, Hart’s national field director and the floor manager during the ’84 Democratic National Convention, speaks even more bluntly. After New York Gov. Mario Cuomo delivered his famed “Tale of Two Cities” keynote address at the convention, Ridder went on the record, calling what had just happened “a wonderfully delivered speech that is absolutely backward thinking.” Cuomo, an old-style Democrat, fit the us-versus-them narrative of a generational fight over the direction of the party.

“Of course, all these people loved it,” Ridder says. “The problem was, and I still say it, he gave no prescription for how to move the party forward. As a result, we had a candidate Walter Mondale, who was so politically inept. And he lost almost every state in the union.”

Still today, Ridder, the president and co-founder of political consulting powerhouse RBI Strategies, thinks that the Democratic Party is in dire need of fresh ideas. The wounds of 1984 never fully healed.

But just a few months before the ’84 convention, coming in second in an eight-way primary, edging out such political heavyweights as astronaut and U.S. Sen. John Glenn, had really sparked a national Hart-mania.

Bill Holen sits in his office, poring over old newspaper articles and photos of a long career in public service that started in 1973. Back then, the man who would later become his boss and friend, a young and lanky Gary Hart, walked into the offices of the Front Range Journal in Idaho Springs, ready for a sit-down interview with Holen, then a reporter at the Journal. Hart was running for the Senate, and he needed the publicity. Holen, who today serves as an Arapahoe County commissioner, delivered. A few weeks later, his phone rang. Hal Haddon, Hart’s campaign manager, asked if he wanted to help organize for the candidate.

A decade later, in 1984, Holen had risen to the ranks of the campaign advance man. After the triumphant Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary nights, he traveled to Pensacola, Florida, to set up a fundraiser. Once again, the learn-as-you-go character of the Hart operation came into full display.

“We raised $50,000 in about 20 minutes,” Holen remembers, reliving his excitement in the room. “And it was all cash. What am I going to do with all this cash? I went to FedEx, stuffed it all into this envelope and sent it — not realizing that it was a violation of the F.E.C. [disclosure] requirements.”

Holen didn’t even have the names of the donors. Most of the money couldn’t be used.

“There was a lot of enthusiasm among what we would call the yuppies, the young intellectuals — college-educated, active, committed, baby boomers, essentially,” he recounts. “We could always find supporters wherever we went. They were generally lawyers or college professors that were very active politically.”

But the longtime Hart friend knows all too well that the candidate never enjoyed the back slapping and posturing of fundraising to begin with. His boss liked to retreat into deep thoughts and meaningful conversation rather than go out of his way and ask for a quick buck.

“We’d go to an event, sponsored for him, and he’d stand in the corner,” Holen remembers.

He knew what to do next. Go to the bar. Order a double shot of tequila. Problem solved.

“Boy, he was the most talkative guy,” Holen says, now laughing.

Already during his days in the Senate, Hart had turned many a quick meeting into a tutorial session, soaking up new information like a sponge to further broaden his horizon. Among his visitors, the senator’s bona fides didn’t go unnoticed. Hoog, his former chief of staff, remembers plenty of meetings that ended with the suggestion Hart should consider running for president.

The senator’s next question, Hoog says, would always be, “Why?”

“His thirst for knowledge and his willingness to reach out in a sense began to equip him better than most to deal with the complexities of being president,” Hoog says.

But there was a crux that he believes helped keep his former boss from ever moving into the Oval Office after the 1984 election.

“I don’t think we ever really talked about the complexities of running for president. In fact I don’t think we ever had three conversations on that topic. He was totally prepared to be president, probably less prepared for running for it.”

And so, when during the heyday of the primary season Mondale came out swinging at a televised debate in March, attacking the senator’s proposals with his “Where is the beef?” line — cribbed from a popular TV commercial for the hamburger chain Wendy’s — the Hart campaign was startled.

For years, they had fought the press on the notion of Hart being called a Tory Democrat, a wonky all-policy-no-style guy.

“All of a sudden somebody says, ‘Where is the beef?’” Hoog remembers. “I don’t think Gary or anybody on the staff took that seriously. It was almost laughable. But that’s one of the things about campaigns: You never know what is going to grab hold.”

While Hart was out fighting tooth and nail in 1984 to pull off another last-minute miracle and somehow clinch the nomination, Buie Seawell, who had by now taken the reins as Senate chief of staff, sat back in Washington, D.C., overseeing a smoothly run constituent service. One step removed from the daily campaign trail craze, Seawell saw that his boss was on a doomed path.

“You never say you set yourself up for the next cycle, but in our hearts we knew in 1984 there was no beating Reagan,” he says. “When that ’84 race was over, Gary Hart was the next one in line for 1988. Polling showed that the party had come back together around him.”

The rest, of course, is history.

Susan Barnes-Gelt, a local Denver political activist, was supposed to join the presidential frontrunner’s campaign in 1987 as a fundraiser when the Donna Rice quake shifted the tectonics of U.S. politics. Barnes-Gelt has known Hart for years.

“Gary Hart’s relationships paved the way for Bill Clinton,” she says. “I know Bill Clinton, I know him well. And Bill Clinton is no Gary Hart. Bill is brilliant. But he is a politician. Gary Hart is like a 360-degree person. He is too good for politics, in a way.”

There it was, once again, the unspoken, What if?

“I’m not saying the world would be different in 2016 had Gary Hart been president,” Barnes-Gelt admits. “It probably wouldn’t be. But it’s gotten worse. What took him down is the reason why serious people now won’t even think about running for office.”

One person many Hart companions consider serious is former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, who in 1984 worked on Hart’s Iowa team, driving the senator around, occasionally picking his brain on policy. This time around, O’Malley has followed in Hart’s shoes and is now running a long-shot campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination himself.

“The 1984 campaign wasn’t successful in real terms,” says Hirschfeld-Zeller, who worked under Seawell in Hart’s Senate office. “But it set him up to be the frontrunner in ’87. There seems to be someone with a lock on the nomination this time, too. But perhaps Martin believes that what he is doing right now will put him in a good position four years from now.”

Hirschfeld-Zeller quit presidential campaign jobs long ago. Today, she fights Colorado ballot measures, such as the recurring personhood amendment. Other former Hart staffers have left politics altogether, pursuing, for example, legal careers. No matter what they do, though, they will always be on Team Hart.

“Anyone who worked for Hart in that ’84 campaign is fundamentally a cause person,” says Hirschfeld-Zeller. “Even if they went to work in something else, I would guess their volunteer time extends in some form to making the world a better place. Those were the kinds of people Gary attracted.”

Lars Gesing is assistant director of CU News Corps, an explanatory journalism project at the University of Colorado Boulder. He is a former intern at The Colorado Statesman and has traveled the country, visiting every presidential battleground state for his project States in Play.