Michael Bennet and ‘the question’ | SONDERMANN

The train usually runs only one way. The route goes from the state Capitol to Washington, D.C. State legislators become members of Congress; governors become senators. See Hickenlooper, John.

Including our junior senator, no matter his years, a total of 12 current U.S. senators arrived there after first serving stints as governors of their respective states. That count includes both such lawmakers from New Hampshire and Virginia.

The reverse trip is infrequently taken. Senators rarely come back to seek state-level office. An academic study shows that, since 1900, 153 sitting or former governors have become senators, while a mere 21 senators have taken the ride home to be elected governor.

This year represents either an aberration or the start of a different trend. Four incumbent senators, two from each party, are seeking the governorships of Alabama, Tennessee, Minnesota, and, yes, Colorado. Though Alabama’s Tommy Tuberville, a legislator with all the qualifications of a football coach, is at the end of his Senate term.

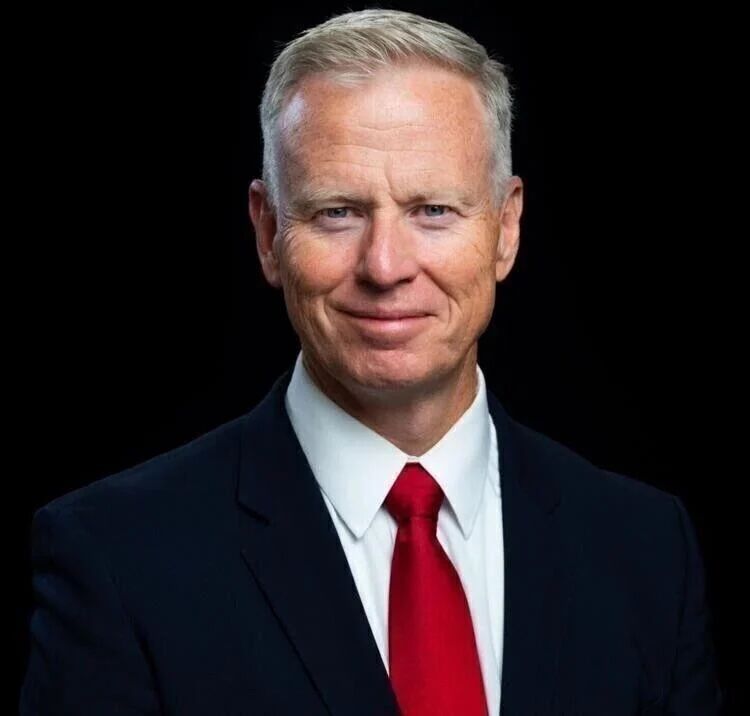

Michael Bennet was appointed to the Senate in January 2009. He was subsequently elected to the body three times, most recently in 2022 by a walkover of 14.5 points. His current term extends to January 2029.

A thoughtful, diligent guy and a senator, unlike some, involved deeply with the country’s most important issues, Bennet has a well-formed rationale in his own mind for the question of why he is seeking to make this shift.

He finds the Senate to be a dysfunctional institution (self-evidently true), thinks his party’s leadership is failing the moment (also hard to argue), and believes he can make a bigger difference in the state’s executive chambers. I do not doubt the sincerity of Bennet’s conviction. Even if it comes mixed with both frustration and ambition befitting any politician.

At the center of this nomination contest between Bennet and Attorney General Phil Weiser is the question of, “Why is Michael doing this?”

The answer might be clear in Bennet’s head, but that does not mean it is registering with Democratic primary election voters or is satisfying their skepticism.

As I read it, the Democratic mood these days is one of dismay and depression at their powerlessness in the face of daily violations of core values, together with a slowly growing hope for a reversal this November.

Sometimes openly, sometimes just beneath the surface, Democrats are questioning Bennet’s timing. It comes in various forms, but at its core is a doubt about his desire to leave the Senate mid-term and absent himself from what is perceived as the essential role of Democratic senators to resist all things Trump.

Bennet has an explanation, but it is simply not getting through.

Complicating his predicament is his own calculated coyness about the selection of a senate successor should he win the governorship. Bennet has never been an elbows-out sort of politician. It is not in his persona. His power play rings as discordant and out of character.

Whether the nod would go to Joe Neguse, Brittany Pettersen, Jason Crow, Jared Polis, or Mike Johnston (color me dubious about the prospects of the latter two), many Democrats who matter feel they are being played and resent being kept in the dark. Bennet’s assertion that he has not really thought about a possible replacement fails the credibility test, especially given that he first came to the office via Gov. Bill Ritter’s surprise appointment.

Compounding Bennet’s struggles is his identity as an establishment kind of Democrat in what is shaping up to be an anti-establishment year. That tag is not necessarily fair. Bennet was among the first prominent Democrats to suggest that President Joe Biden step aside well over half a year before the disastrous debate performance.

Still, perceptions are what they are. Having been on the scene for a couple of decades, having made his share of necessary compromises and having voted for a handful of Trump nominees, Bennet can hardly don the hat of outsider.

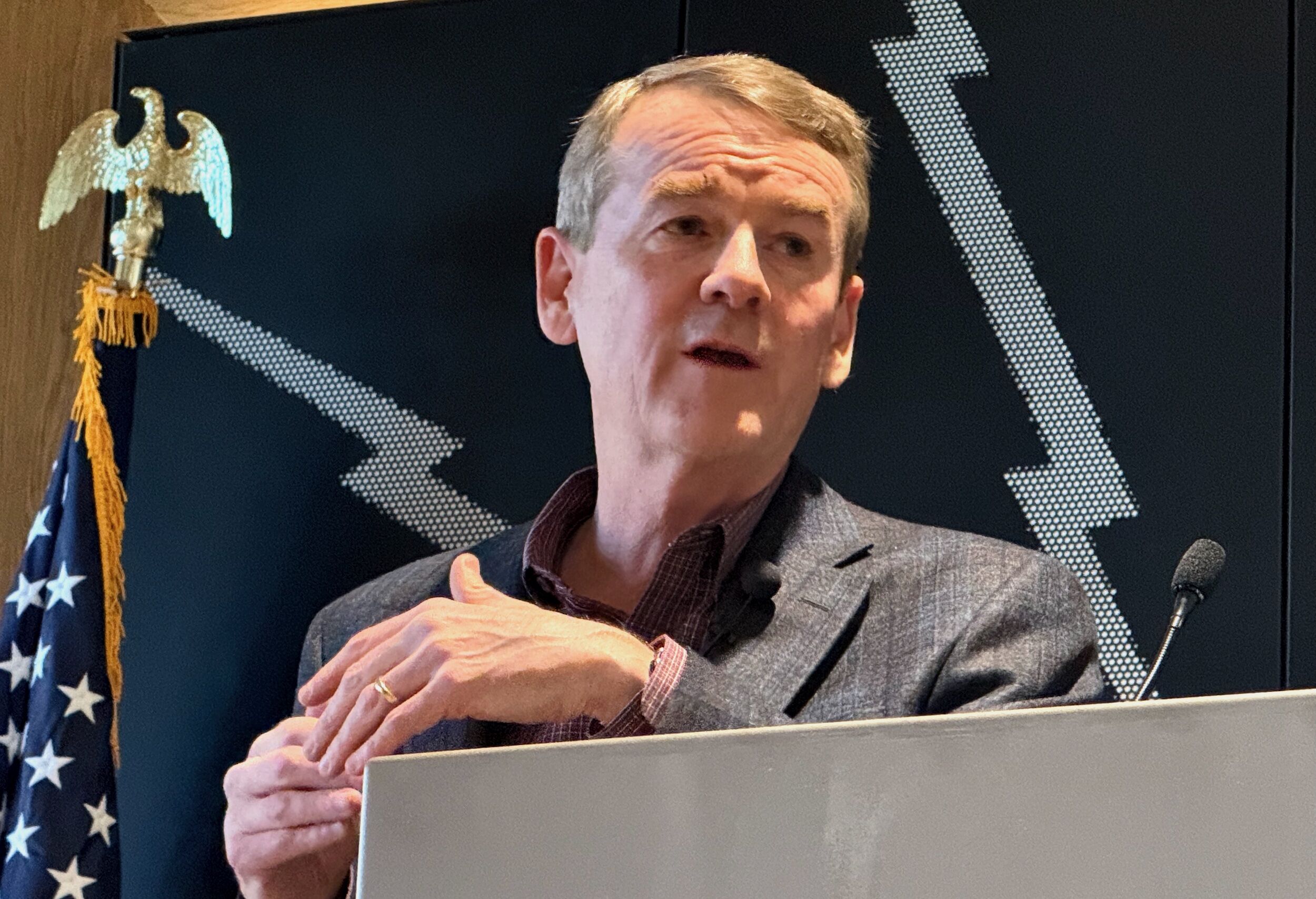

That garb really does not fit Weiser either, with his years in Obama’s Justice Department, as a law school dean, and then as the state’s chief lawyer. But Weiser has been better able to capture that rebel, insurgent energy for which Democrats are searching. Having sued the Trump administration a half-zillion times doesn’t hurt.

All said, this is a campaign of small differences. It is hard to imagine the policies and governing style of Bennet and Weiser being all that far apart. Nonetheless, they give off a different vibe in an era when such an aura has supplanted most other criteria.

Forget November. Colorado’s next governor will be chosen in the June 30 primary election. Such is the afterthought status these days of the state’s Republican Party.

Michael Bennet has proven himself a political winner. He clearly wants a vote on parole from the Senate. But unless he can more convincingly answer the question of “why” and “why now,” Democrats are likely to send him back to Washington to complete the remainder of his sentence.

Eric Sondermann is a Colorado-based independent political commentator. He writes regularly for Colorado Politics and The Gazette. Reach him at EWS@EricSondermann.com; follow him at @EricSondermann