Federal judge opens new front in effort to increase magistrate judge handling of civil cases

One of Colorado’s federal judges rang in the new year with a new effort to spread out the U.S. District Court’s civil caseload among its roster of magistrate judges.

“NOTICE ENCOURAGING CONSIDERATION OF CONSENT,” Judge S. Kato Crews has written in docket entries across at least nine recently filed civil cases so far. “This district’s magistrate judges play a crucial role in the work and structure of the district court and the administration of justice.”

In contrast to the life-tenured district judges, who the president nominates and the U.S. Senate confirms, magistrate judges are hired to eight-year terms through a merit selection process. They tend to handle preliminary and administrative matters in cases, as well as evidentiary disputes and settlement conferences. When both a district judge and a magistrate judge are assigned to a case, the magistrate judge may also evaluate and recommend on motions, with the district judge making the final decision.

However, if the litigants all consent, magistrate judges can handle civil cases entirely on their own, with appeals going directly to the circuit and supreme courts.

Colorado Politics identified nearly a dozen instances, beginning on Dec. 23, in which Crews filed docket entries encouraging litigants to consent to a magistrate judge handling cases assigned to him.

“There are many benefits to consenting. One such benefit is having a single judicial officer preside over every aspect of your case rather than two,” he wrote. “Consent to magistrate judge jurisdiction is voluntary, and no adverse consequence will result if one or more parties decline to consent.”

He added that, because district judges handle felony cases, which can take precedence over civil lawsuits under the speedy trial guarantee, a magistrate judge could bring a civil case to trial more expeditiously.

“I thought perhaps this may help parties give considered thought to the benefits associated with consent,” Crews told Colorado Politics in response to questions about his new practice. “My hope is that it will aid attorney conferrals over consent and give the lawyers a specific frame of reference when discussing the consent option with their clients. The magistrate judges have expressed their concerns over declining consents, and I feel it’s important to try to address those concerns.”

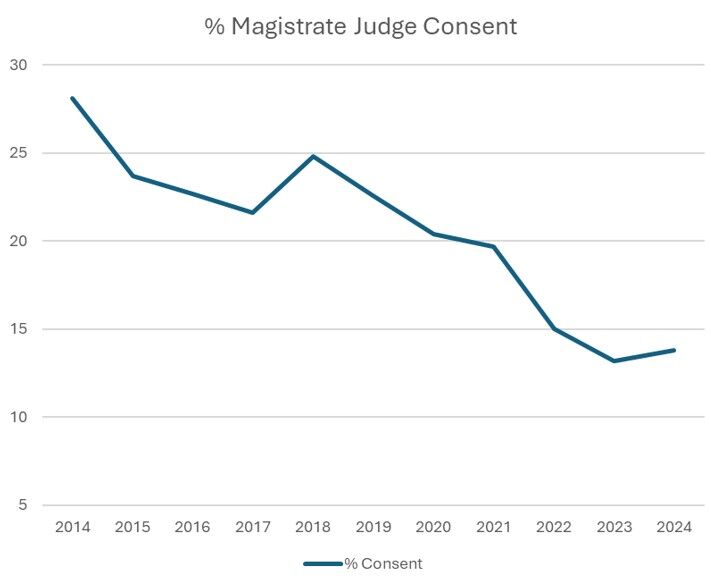

Statistics compiled by U.S. Magistrate Judge N. Reid Neureiter last fall showed that in 2024, parties were consenting to a magistrate judge’s handling at a rate of about 14%. A decade prior, the rate was double that.

“I hypothesized reasons why,” Neureiter told Colorado Politics in October. “But the answer is I don’t know. And nobody knows why.”

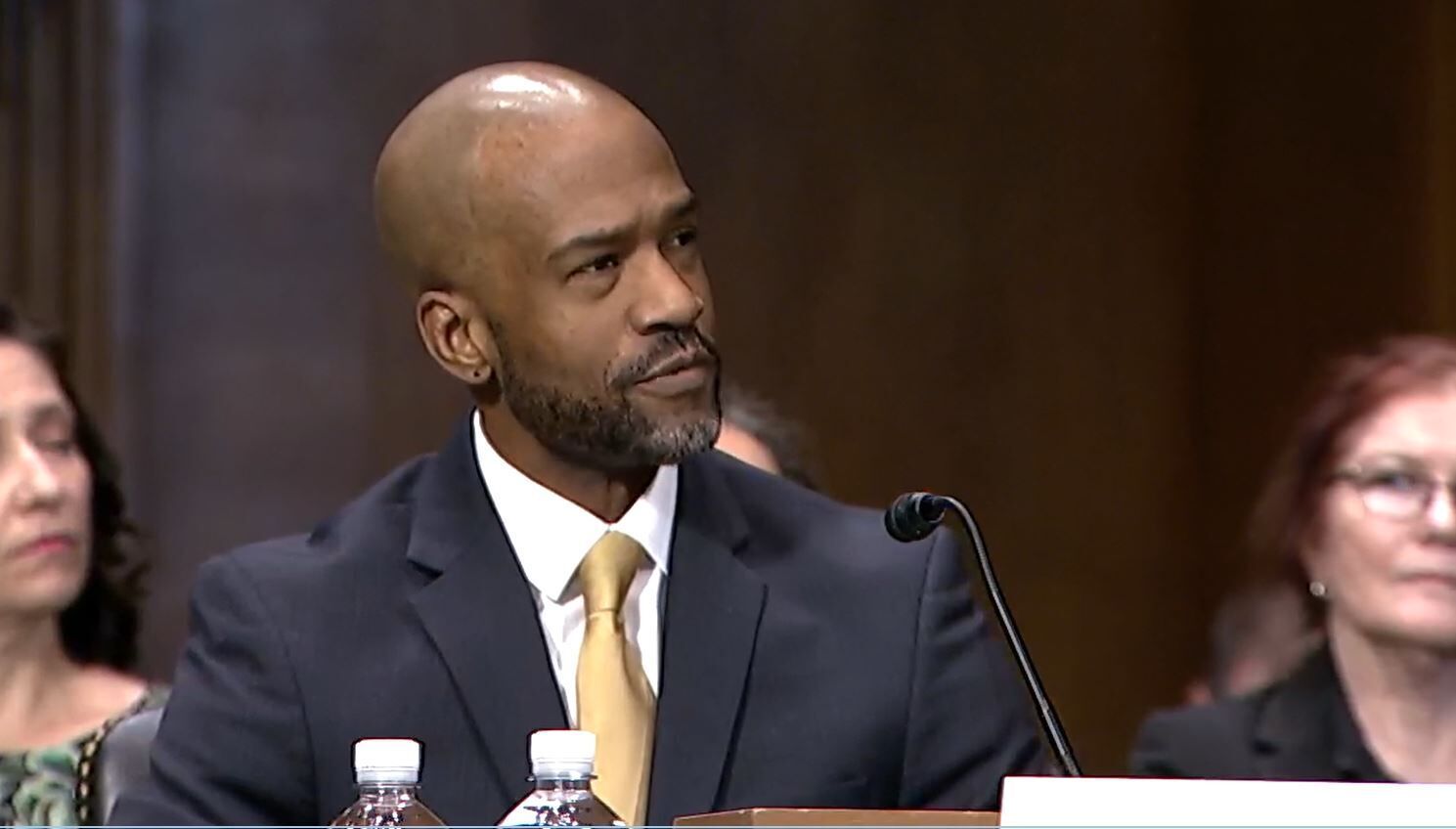

Crews, who was a magistrate judge for several years before his 2024 appointment to the district judge bench, spoke about the subject in early 2025 with Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney at a sparsely attended legal event.

“Nobody wants to talk about why they’re consenting or not consenting,” Sweeney said, commenting on the attendance level.

“I’ve estimated spending at least 500 hours a year, if not 700 hours a year, on criminal matters,” she added. Under magistrate judge consent, there is “a lot more time and attention they can give to your case.”

However, not all of Crews and Sweeney’s colleagues are receptive to increased handling of civil cases by magistrate judges.

In 2011, Senior Judge John L. Kane authored a statement disagreeing with a rule change at the court addressing magistrate judges’ authority to hear cases. Kane, joined by Senior Judge Lewis T. Babcock and the late Senior Judge Richard P. Matsch, indicated he was “deeply concerned by the relentless delegation of this court’s constitutional duties” to members of the bench who are not nominated and confirmed pursuant to Article III of the U.S. Constitution, as district judges are.

“Being an Article III judge is not merely a job. It is the embodiment of an independent and structurally fundamental separate branch of government,” Kane wrote. “One may consent to using the stairs to access the third floor of a building. One cannot ‘consent’ to the building’s architecture, which, having been carefully conceived, is essential to its structural integrity.”

Kane declined to comment on Crews’ new practice of encouraging civil litigants to consent to magistrate judges, but he confirmed he still feels the same as he did in 2011.

“The Constitution, in my view, controls, and it specifically states that cases and controversies are to be decided by judges appointed under Article III,” he wrote in an email. “In my view, it is not a matter of convenience; it is a matter of properly designated authority.”