Denver may revise animal bite penalties to consider criminal intent

Denver pet owners are responsible for bites and injuries caused by their animals, facing both civil penalties and criminal charges of up to $999 and 300 days in jail.

However, some city officials have suggested that the city consider revisions to the municipal code regarding animal-related violations, including adding “criminal intent” elements to some violations and converting others to civil infractions.

The officials would also like to see better inter-agency collaboration, especially in cases that cross jurisdictional borders, they said.

Denver Municipal Code Chapter 8 governs animals, including regulations for owning pets, and all of the animal violations in that chapter potentially expose residents to the city’s maximum penalty, Colette Tvedt, Denver’s chief municipal public defender, told Health and Safety Committee members on Wednesday.

“There are so many ordinance violations contained within that chapter, animal-related noise, leash-law violations, barking dogs, rabies vaccination, and the more serious offenses that you talked about today, and some of these offenses, including the attack and animal bites, are a strict liability offense,” Tvedt said. “And so, what that means is that there’s no mens rea involved, or what is the state of mind.”

A strict liability offense, according to Black’s Law Dictionary, is a crime in which the prosecution doesn’t need to prove that the defendant intended to break the law or cause harm to secure a conviction.

An example might be a case in which a dog with no history of aggressive behavior bites or attacks someone, while the owner is out of town.

“What we’re asking for, City Council, on behalf of the Office of the Municipal Public Defender, is just to take a look at the code, see if there are some areas that we can clean up, make them civil, and the ones that would remain would have a mens rea element,” Tvedt said.

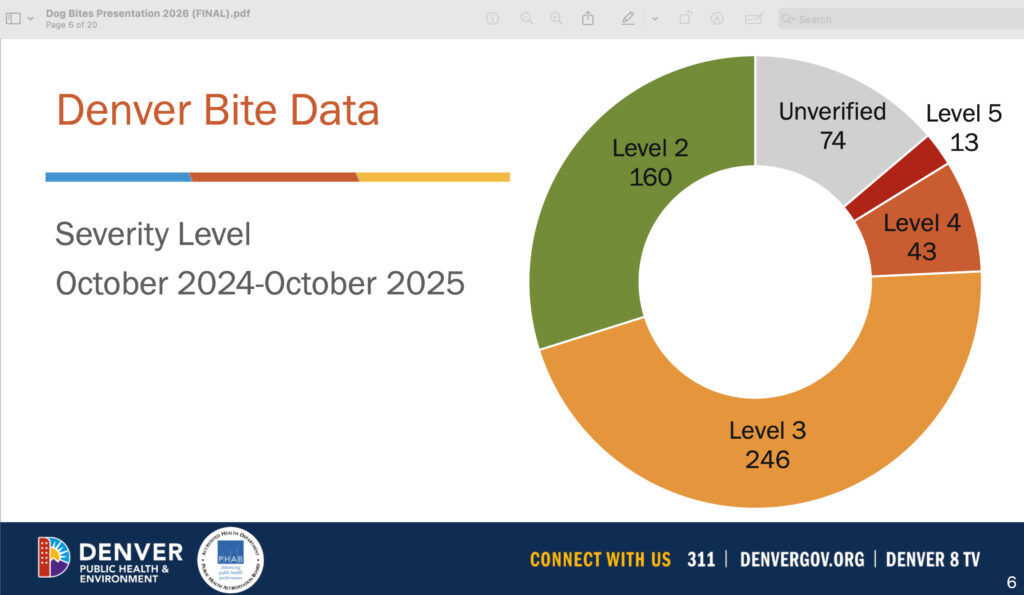

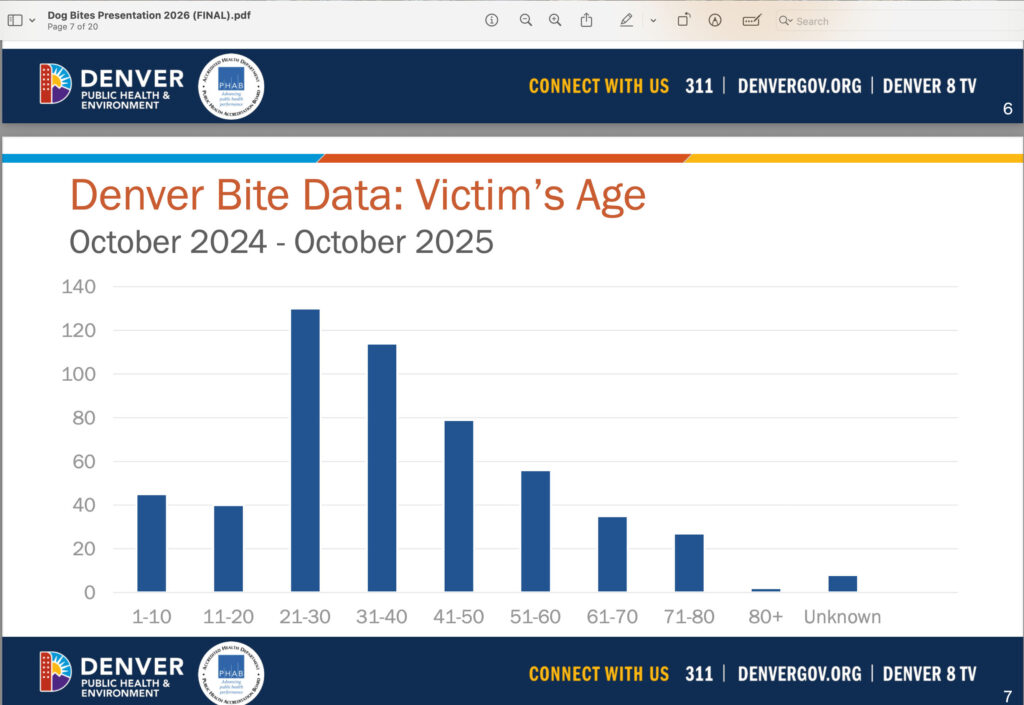

DR IAN DUNBAR BITE SCALE

BEHAVIOR-BASED LAWS

While the city does not have an outright breed ban, under Denver’s Ordinance Sec. 8-67, restricted breeds, such as the American Pit Bull Terrier, American Staffordshire Terrier, or Staffordshire Bull Terrier, are prohibited unless they have been issued a provisional breed-restricted permit, according to the city’s website.

Permits for restricted breeds may require an evaluation in some cases.

Permitted animals must also be microchipped, vaccinated against rabies, and spayed or neutered.

City animal protection officials argued that behavior-based laws are more effective than overall breed-based bans because they target actual aggression and not the animal’s breed or appearance.

When it comes to dog bites, Joshua Rolfe, a lieutenant with Denver Animal Protection, said dog breeds are misreported regularly.

“You know, the general public is not great about identifying dog breeds,” Rolfe said. “A lot of people are dog people, but it’s for the specific dog breed that they like. So, oftentimes we’ll get, ‘It was a large, brown, short-haired dog,’ and that could be any number of dog breeds.”

Dog breeds are usually not entered into a report until an officer has seen the animal first-hand.

“There’s a misnomer that dogs can be rehabilitated from a bite incident. You put them through a training course, and then you don’t have to worry about it again, because they’ve been trained not to do that,” Rolfe said. “That’s actually not true.”

Even with sufficient training, owners will have to manage the animal’s behavior for the rest of its life.

“A vast majority of animal bites that occur nationally go unreported,” Rolfe said. “They generally happen within somebody’s home and tend to be fairly minor incidents with family members, and people don’t seek medical attention for those.”

Doctors and medical offices are required to report animal bites.

“In Denver, we have an ordinance that requires anyone with knowledge of an animal bite to report that to the health department,” he said.

NEED FOR MORE INTERAGENCY COOPERATION

Dog bite incidents don’t always respect jurisdictional boundaries, and that worries District 5 Councilmember Amanda Sawyer.

“So, District 5 borders both Aurora and unincorporated Arapahoe County and Glendale,” Sawyer said. “And we see a lot of stuff happen across borders all the time.”

Sawyer referenced a case, in which a third attack by the same group of dogs occurred on the border of Denver, but the animal’s owner was a resident of Aurora.

Rolfe acknowledged that competing ordinances and laws impact what different agencies can do.

“For example, in the city’s municipal code, any city official who does enforcement, apart from Denver police, who enforces state laws, cannot go outside the city and county boundaries to issue criminal summons under the municipal code,” he said.

Rolfe added that his agency has collaborated with Denver police and the District Attorney’s Office to issue citations to the owner.

No proposed legislation was referred to the City Council by members of the Health and Safety Committee.