Colorado campaign finance penalties ‘a runaway train without an off-ramp’

Each day, Mike Stapleton wakes up owing the state of Colorado another $1,550.

By the end of each week, Stapleton’s debt for not filing nearly three dozen campaign finance reports dating to April 2018 will have grown by nearly $11,000.

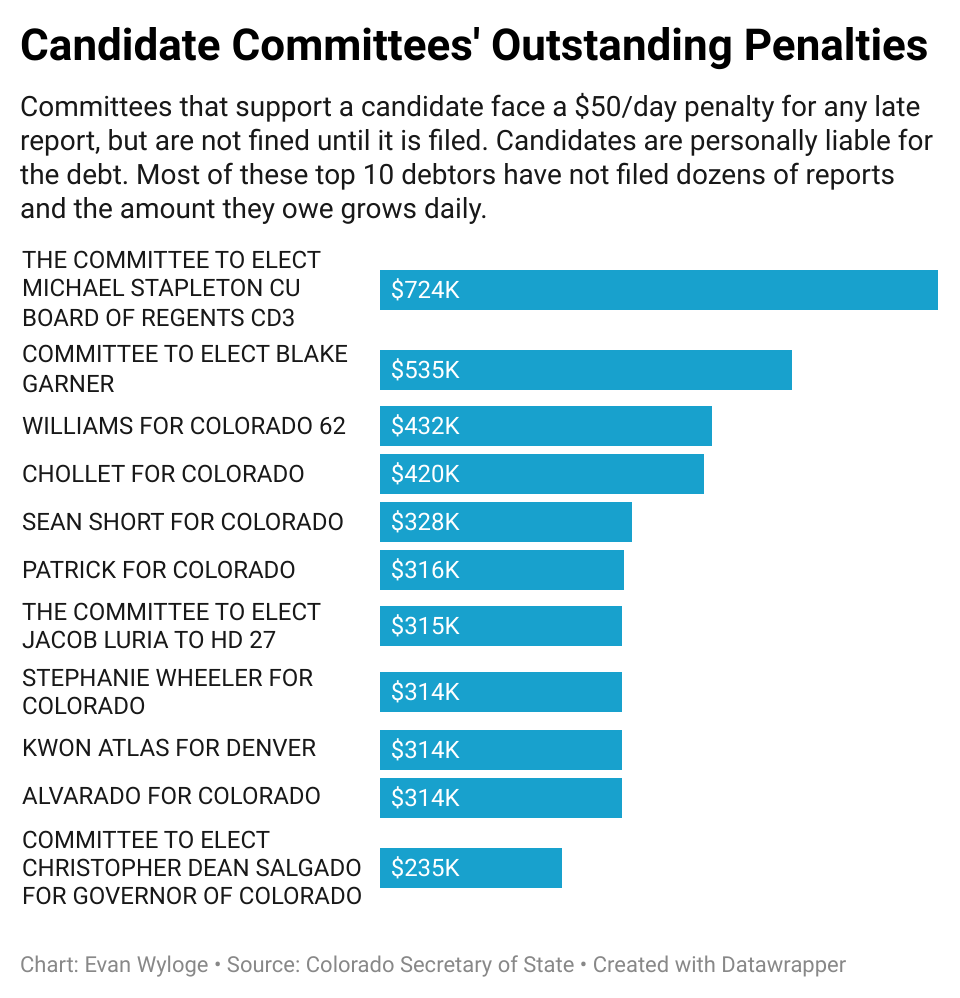

As of Dec. 8, Stapleton and his campaign – The Committee to Elect Michael Stapleton CU Board of Regents CD3 – owes the state $721,000 in penalties for those unfiled reports.

And the amount keeps mounting with each passing day, growing even more with every new financial disclosure report that comes due, regardless that Stapleton, a Libertarian, years ago lost his bid for the CU board by a huge margin and never plans to run for office again.

“This has gone beyond ridiculous,” Stapleton, who lives in New Hampshire, said via email. “I never raised any funds nor had any expenditures in the first place. I’m just a working-class single man.”

A Denver Gazette review of campaign finance records with the Colorado secretary of state’s office found that Stapleton’s committee tops among more than 420 committees, office holders, groups that represent specific causes, political action committees and unsuccessful candidates that owe more than $13.5 million for not filing campaign finance reports on time – or, in Stapleton’s case and others like him, not at all.

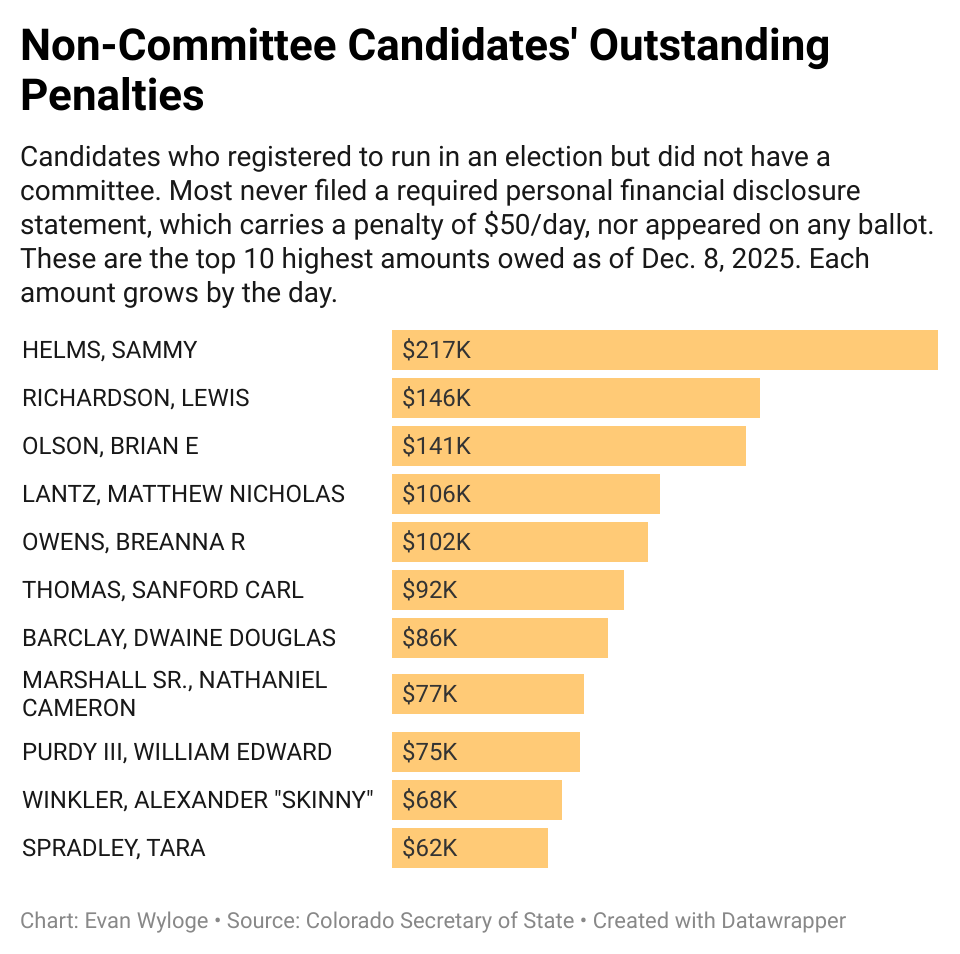

In dozens of other cases, The Denver Gazette found among the debtors would-be candidates who merely registered for an election but never actually appeared on the ballot or raised any money. Yet, because state law requires even a potential candidate to file a personal financial disclosure statement – regardless of whether they ever run – a missed reporting deadline after such a statement is filed means a $50-per-day penalty.

One of them, a potential Democratic candidate for governor, amassed more than $350,000 in penalties dating to 2014.

And there are scores of others with running tallies that have mushroomed into the tens of thousands of dollars.

But The Denver Gazette found a major flaw in the state’s campaign finance laws that makes the penalty system worse: As long as the candidate or committee facing the fines doesn’t ever file the missing reports, the state can’t actually levy any penalty.

That’s because state law mandates a missing report must first be filed before a penalty assessment can be made.

It’s a runaway train without an off-ramp.

“This is basically a disgrace,” said Pam Feely, a longtime campaign finance expert and author who literally wrote the book on it, “Candidates Guide to Campaign Finance in Colorado.”

“This isn’t serving the public interest at all,” she said.

The top three dozen debtors account for $11.3 million – roughly 84% – of the total owed, The Denver Gazette’s review found.

And it’s unlikely the state will ever see much of it because its collection system is little more than a toothless tiger.

In the case of nearly every debtor, The Denver Gazette found fines tolling non-stop at $50 per day for at least one missed finance report no matter the reason for the delay, and many of the people whose names appear on the state’s public-facing website declaring their debt said they had no inkling it even existed.

Some have missed dozens of reports, often for years, mostly because they simply packed up after an election loss and never bothered to finish the paperwork.

But aside from candidates – who by law can be held personally accountable for the debts of any committee that specifically supports them – groups such as PACs or those created to back a specific cause or issue aren’t liable for their arrearages, The Denver Gazette found.

In fact, state election officials affirmed that those groups are essentially immune from collection efforts because there is no responsible party to go after, which essentially negates any requirement to file the campaign finance report in the first place.

So, why do they?

“You have leadership PACs, candidates, small-donor committees, issue groups, and all the ones I’ve ever worked with wanted to ensure they were legal, so they do what the law says and they file their reports on time,” Feely said. “In my 20 years doing this, I’ve woken up at 12:02 a.m. and said, ‘Holy cow, I forgot to file!’”

‘A complete gut-punch’

The Denver Gazette also found those people – both candidates and the registered agents who run committees – in charge of multiple groups with long-running penalty assessments, some of them while they were still serving in the elected office they were to supposed be filing reports about.

There is no prohibition against serving in – or running for – office while in violation of campaign finance laws. The lone prohibition is candidates cannot appear on the ballot if they’ve not filed a personal financial disclosure statement.

“It kind of just got away from me,” said Patrick Neville, a three-term representative of House District 45, which includes much of Douglas County, from 2015-2021. “I thought I was done with all of this. Your call is a complete gut-punch to me.”

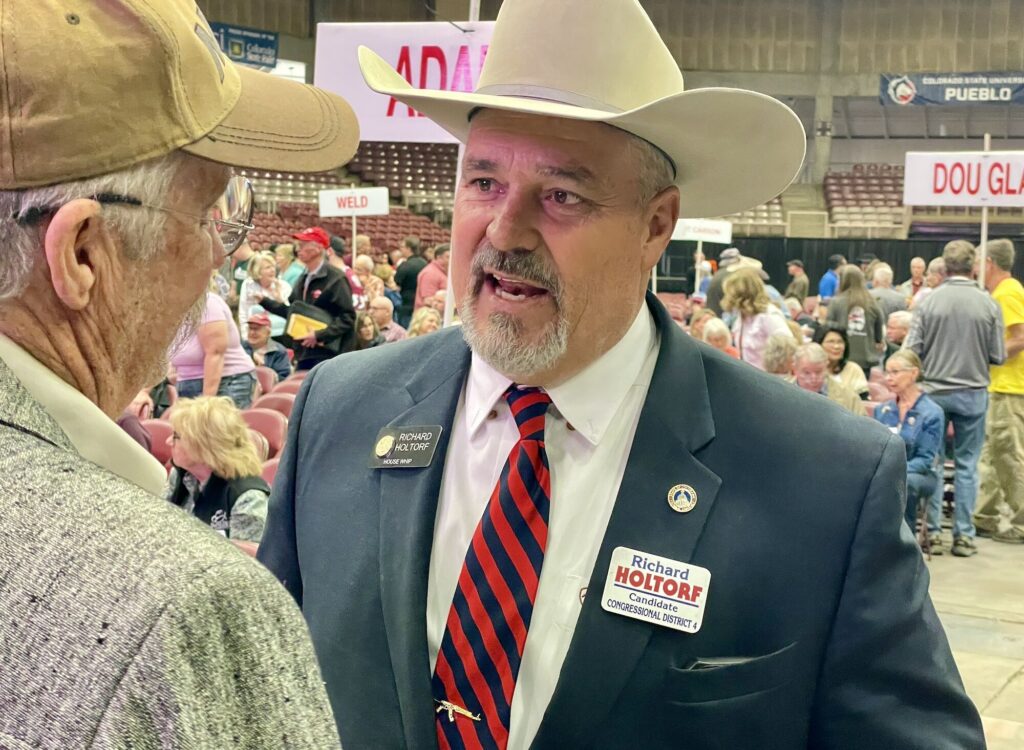

Neville’s Patrick for Colorado committee is nearing $314,000 in penalties for not filing 16 campaign finance reports since January 2024, and for filing 17 other reports late. In all, Neville had been levied penalties for the missed or late filings every year he served in office.

The secretary of state’s office, by law, is supposed to send invoices warning of unpaid fines and delinquency letters about the mounting debts to a candidate’s home address and email address. Each comes with a warning that the state can send the matter to collections if unpaid.

Records show such notices were sent to Neville as required – 109 times.

He’s paid none of them.

“I never saw any mail or email,” Neville insisted, confirming his Castle Rock address remained unchanged, though the email affiliated with his campaign committee, he said, was “long closed.”

Records show Patrick for Colorado had $14,837 on hand when it made its last public filing on Jan. 23, 2024 – a week late. It’s unclear what became of those funds, but committees cannot be terminated unless bank balances are zero.

Additionally, Neville created a PAC – Patrick PAC – in June 2014, seven months before taking office. The PAC was meant to “support Patrick Neville and pro-liberty conservative candidates running for office,” according to its registration paperwork. Because Neville was its registered agent and a direct beneficiary of its funds, campaign finance experts said he’s likely liable for any penalties it accumulates.

And there have been many.

Like his campaign committee, Neville’s PAC racked up identical penalties for late or missed filings with the secretary of state, more than $310,000, and generating the same number of delinquency letters – 109 of them.

Because the PAC has at least 16 unfiled reports – the same as his campaign committee – Neville’s debt continues to grow by $1,600 each day.

The PAC still had $4,860 in its account when it last filed a report in January 2024, records show.

Between the two committees, as of Dec. 8, Neville is on the hook for more than $626,000, ticking upward each day.

“I honestly thought I closed those accounts out and was all done with those official duties,” Neville said in a telephone interview. “I guess I should check it out.”

Amendment requires ‘strong enforcement’

Colorado’s campaign finance laws are constantly tinkered with.

Deadlines, contribution limits, types of committees, and penalties for violations are all part of the broader series of rules delineating how the finances behind the electoral system should operate.

The goal, ultimately, is transparency.

Since 2021, the Colorado General Assembly has taken up nearly a dozen bills with some component of campaign finance reform, records show. Voters even approved a constitutional amendment in 2002 that laid out campaign and political finance law.

Article XXVIII, which was Amendment 27 in that election, was passed by 66% of the vote. Its opening reads:

“The people of the state of Colorado hereby find and declare that … the interests of the public are best served by … providing for full and timely disclosure of campaign contributions, independent expenditures … and strong enforcement of campaign finance requirements.”

The law allowed the secretary of state’s office to make whatever rules necessary to comply with the amendment, and that office has a 97-page manual outlining each of them.

Each election cycle relies on a calendar of due dates, when reports that cover specific time periods are due. Those reports are crucial for the public to know from whom candidates or committees accept money, how much and, just as critical, what the funds are spent on.

“In cases since the 1970s and culminating in Citizens United in 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court has steadily eroded the ability of Congress and state legislatures to curb the influence of money in politics,” said state Sen. Mike Weissman, D-Aurora, who has sponsored several campaign finance-related bills. “Just about all that’s left is disclosure and disclaimer – timely, publicly accessible reporting of money raised and spent and annotations on political communications who’s paying for them.”

All sides of the political aisle intently monitor the goings-on of others, frequently filing complaints or challenges any time even the smallest infraction is perceived.

For instance, Larimer County state Rep. Ron Weinberg, R-Loveland, is facing an inquiry into his use of campaign funds following recent allegations that, since 2023, among other things, he’s paid hotel bills in Blackhawk and bought nearly $400 in cigars using campaign funds.

The expenditures likely would have been unknown publicly without the campaign finance reports that delineated them.

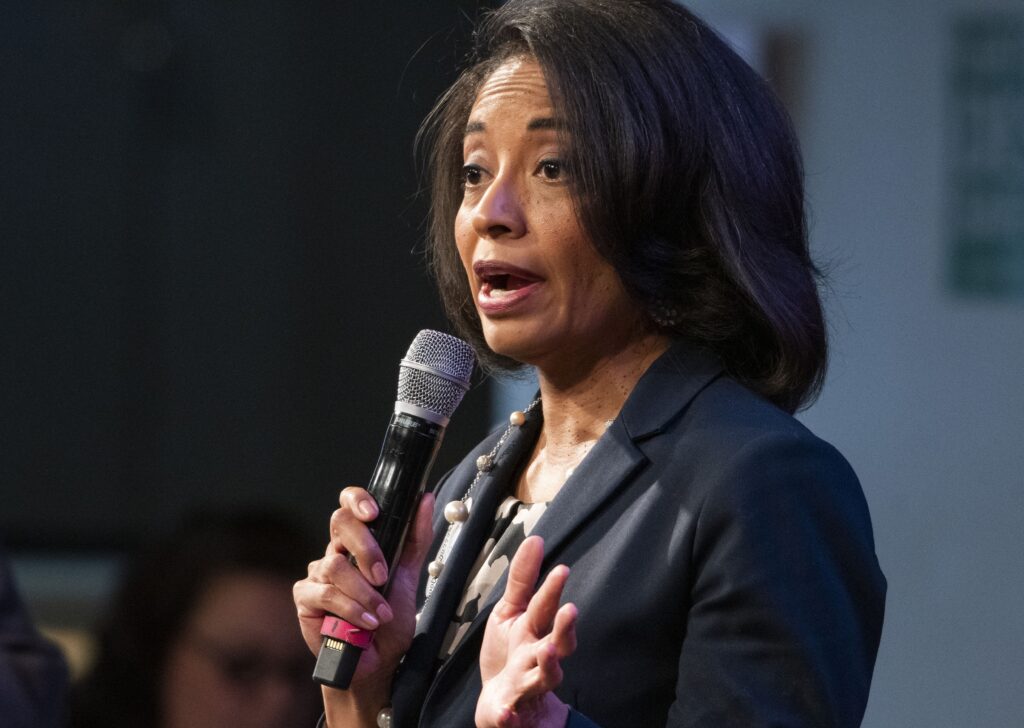

Similarly, Secretary of State Jena Griswold and Attorney General Phil Weiser each currently face complaints in their respective bids for attorney general and governor, respectively. Those complaints allege violations for not identifying some contributors, their occupation or employers in filings.

U.S. Sen. Michael Bennett faces a trio of complaints asserting a misuse of his federal campaign funds in his state run for governor.

The complaints are all pending and have not generated any penalties, but without the related campaign finance reports, the public would not have spotted any of the alleged misdeeds.

Although campaign-related complaints filed with the secretary of state kick off inquiries that measure their validity, those involving overdue or missing reports like the ones examined by The Denver Gazette are automatic.

And each infraction generates a letter from that office warning of the $50-per-day penalty for each day the filing is in arrears.

Each delinquency letter – they are generated every 60 days for each violation – contains a grid showing how long a particular report is late and the amount of the penalty to that point.

More critically, however, is a one-sentence, bold-faced advisement regarding the problem.

“Please note: No payment is due at this time. Once the report is filed the committee will receive a final statement for the full amount of the imposed penalty.”

The letter also warns of potential collection actions that can be taken “60 days after the final statement letter (once the report has been filed).”

In essence, no report, no penalty.

Ryan Williams said he caught on very quickly. He ran unsuccessfully in 2022 for state representative in House District 62, losing in the Republican primary to Carol Riggenbach, who eventually lost to Democrat Matthew Martinez.

Records show his committee, Williams for Colorado 62, last filed a report in April 2023 and showed no money on account. The extent of Williams’ fundraising had been a single $150 contribution from a Monte Vista farmer and $60 from smaller contributions before the primary.

The committee missed the next 19 reports – long after he lost his primary bid – and, with penalties racking up at $950 per day, it owes nearly $429,000 as of Dec. 8, records show.

“Why should I even pay it if you won’t charge me until I file?” the former La Jara, Colo., resident and TSA officer said from his Alaska home. “There’s no way on earth I can pay it, and if I don’t run for office ever again, that bill never comes due.”

Williams said it’s been years since he used any of the addresses where the secretary of state’s office is sending delinquency notices. Colorado election records indicate the state has sent 150 delinquency notices to those addresses since July 2023.

“I haven’t done a thing for campaigning since the day I lost,” he said. “Why aren’t these things just automatically cleaned out, like voter rolls? There’s no money, it’s not active. Now, I owe them money? That’s nuts.”

Griswold’s office noted that state law doesn’t allow for inactive campaign committees to be placed on stasis automatically.

Candidates and committees can request a penalty be waived – this is only if they file the report first – and must provide an excuse for having missed the deadline.

Those excuses are rarely deemed good enough, frequently falling into the category of the dog ate the homework, and are similarly denied. Many violators gave up after one or two tries, even though they are allowed a waiver request for each penalty assessment. Miss a dozen reports, a committee gets a dozen waiver changes, one for each.

Campaign committees rarely terminated

Colorado campaign finance law allows the secretary of state to terminate a candidate committee should it not file six successive reports – sooner if that happens in fewer than 18 months – an indication it’s inactive and unlikely to be used again.

It can happen, too, for PACs and issues committees. It’s important because the state’s six-year clock on collecting a debt can only begin when it actually terminates a committee and issues a formal penalty for unfiled or late reports.

Yet it rarely happens, The Denver Gazette found.

Each of the committees with the highest current penalty total got there because they owed dozens of reports, not just six, records show.

Mike Stapleton’s committee, for example, owes nearly three dozen consecutive reports dating to 2018. Ryan Williams owes at least 19.

“There is no set timeline for administrative termination decisions to take place,” a spokesman for Griswold’s office emailed The Denver Gazette, responding to a question about why so many delinquent committees exceed the six-report minimum. “All I can tell you is they have not been terminated at this time.”

The committee to elect Blake Garner to House District 22 in Colorado Springs – he is now a deputy district attorney in El Paso County – is no exception.

Records show it hasn’t filed nearly three dozen consecutive reports since December 2022. He lost to Republican Ken DeGraaf.

As of Dec. 8, 2025, the secretary of state says Garner owes nearly $532,000, mostly for the unfiled reports. He’s been sent at least 180 delinquency letters, records show.

Garner returned a call from The Denver Gazette, did not leave a message and then did not return additional efforts to reach him.

RELATED: Colorado campaign debt collection efforts aren’t much of an effort

In a candidate survey by online campaign tracker Ballotpedia, Garner said he was running “because I believe we deserve better from our government. For too long, our issues have merely been paid lip service while our communities suffer.”

He added: “We deserve a government that works for us, and I’m ready to fight for it.”

Records show he also never paid $150 in fines assessed when his committee filed three finance reports in 2022, each of them a day late.

Gardner’s case is a little different, though, in that the committee showed a balance of $485 in its last filing in October 2022.

By law, terminations can only happen when there is no money left.

Little effort on collections

Before 2021, debts owed to the state were to be collected by its collection agency in the Department of Personnel Administration. The legislature changed that and made each department responsible for collecting its own debts.

The secretary of state’s office hasn’t made much more of a collection effort on campaign finance penalties – other than the delinquency letters it generates warning candidates and committees about potential collections, The Denver Gazette found.

That office referred no campaign finance collections to the personnel administration since at least 2018 – the lone referred matter that year was a tax-related collection – a spokesman for that office said.

And since 2021, when departments were holstered with having to chase debtors or farm the work to outside private collection agencies, the secretary of state has made a similar number of requests regarding unpaid campaign debt: none.

“The department of state may choose whether to pursue a collectible debt,” agency spokesman Jack Todd wrote The Denver Gazette. “The department has discretion to determine whether it believes the debt is collectible. These determinations are made administratively within the department on a case-by-case basis.”

Griswold’s office offered no additional explanation.

It’s not as if no one’s paying up – it’s just that the secretary of state isn’t trying to collect.

In 2025, the office collected nearly $17,500 in penalties from 66 different committees, records show.

Of those, 19 were the result of a complaint filed with the secretary of state – typically for a matter other than lateness – and for which a settlement was allowed through an administrative law judge or a hearing officer. The remaining 47 were generally a $50 penalty for a late report and were paid shortly after a warning letter.

“The purpose of fines is to encourage compliance with those disclosure and disclaimer requirements,” Weissman, the state senator, said. “If you’re a little bit late, you owe a little bit. If you’re a lot late, you owe more. By the time we see penalties into the five digits, it means many different deadlines have been missed and have compounded on each other.”

Sometimes without even trying.

Colorado’s first woman Speaker of the House – Lola Spradley – was no stranger to politics nor its campaign finance system. The Beulah Republican served in that capacity from 2003 until 2005, following six years as a state representative.

Somehow, nearly two decades after Spradley retired to Huerfano County, her granddaughter, Tara, was registered to run for House District 46 in July 2022.

The younger Spradley said she never filed the candidate affidavit that bears her name.

No matter. The state said she still owes more than $61,600 for not filing a personal financial disclosure statement back then. State records show she’s been sent 23 delinquency letters telling her about it.

“Are you kidding me?” Spradley said when contacted about the debt. “I’ve been in politics my whole life helping my grandmother, but I never saw any of this.”

She is one of 14 people to owe at least $43,000 for not providing the statement after an affidavit declaring their candidacy was filed, records show. They are required of every candidate, even just potential ones.

The election for House District 46 that year was won by Republican Jonathan Ambler over Democrat Tisha Lyn Mauro.

Said Spradley: “I’ve never run for anything.”