The clock is ticking: Negotiations stall on Colorado River water-sharing pact

With a critical Nov. 11 deadline fast approaching, negotiators from the seven Colorado River basin states remain at odds over how to manage a river that serves 40 million people — and which, experts long agree, is overallocated.

Negotiations are moving so slowly that some basin leaders are questioning whether that agreement will happen before the deadline or whether the Bureau of Reclamation, which still doesn’t have a permanent commissioner, will have to step in.

Negotiations over the “divorce,” as some are calling it, or a “conscious uncoupling,” which is how Colorado negotiator Becky Mitchell describes it, began over the year-long stalemate between the upper and lower basin states.

And then came the bureau’s 24-month study of hydrology, adding a wrinkle that nobody wanted.

The deadline for implementing the post-2026 operating guidelines agreement is Oct. 1, 2026, although the bureau wants everything ready to go by June 2026.

The hydrology report pointed out a near-crisis level at Lake Powell by next year, just as negotiators are trying to come up with a long-term deal that will guide the river’s operations into the future.

Current operating guidelines that were put into place in 2007 will expire next year. However, it has become a much more challenging job to manage the river over the past two decades. This river supplies water for agriculture and supports 40 million people across seven states.

Experts said that’s due to a 25-year drought that has reduced the river’s historic flow by millions of acre-feet of water per year.

One acre-foot of water is about 326,000 gallons, or enough water to cover one acre of land with one foot of water. That’s enough to supply multiple families every year.

On Aug. 15, the bureau issued its two-year study on the Colorado River.

The study projected that Lake Powell’s elevation on Jan. 1, 2026 would be 3,538.47 feet — approximately 162 feet below the complete pool and 48 feet above the minimum power pool, also referred to as “dead pool.”

In June, Lake Powell was at 3,562 feet, about 20 feet less than at the beginning of the water year. Lake Mead was 10% below the start of the water year at 1,056 feet.

That’s about 34% of its capacity; Lake Mead, south of Lake Powell, is at 31% of capacity. That marks one of the five driest years in the last 50 years.

The two reservoirs are the nation’s largest.

Should Lake Powell drop to the “dead pool” level, the power plant at the reservoir’s Glen Canyon Dam would be unable to generate hydroelectric power that is sold across the West.

In a statement, the Upper Colorado River Commission (UCRC), which represents Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico, said the Colorado River system “cannot support long-term water reliability without shifting to supply-based management.” The UCRC said it is committed to “a post-2026 operating framework grounded in actual hydrologic conditions. Long-term solutions must reflect the River’s true hydrology, not unrealistic demands.”

That’s a dig at the Lower Basin states, which have been calling for the Upper Basin states to reduce their water usage.

The Upper Basin states maintain they already take less water than they’re entitled to and that the reductions must come out of the Lower Basin states, which they claim have taken more than they’re entitled to for decades.

The difference is in how the two basin groups have historically viewed their allotments. The Upper Basin states have traditionally taken into consideration evaporation, which reduces the amount of water available.

The Lower Basin states have historically not accounted for evaporation in how they calculate their allotment.

Both groups are allotted 7.5 million acre-feet of water per year, calculated over a 10-year average.

The Lower Basin states, experts said, have been taking up to a million acre-feet more than their allotment, referring to the annual 7.5 million acre-feet allotment as a “delivery obligation.”

That’s in contrast to how the Upper Basin states view it. In a 2023 presentation to Colorado’s Interbasin Compact Committee, Mitchell of Colorado said it is not a delivery obligation but a “non-depletion obligation.”

“There needs to be an investigation of why there is less water in the system — if due to drought, that is not the Upper Basin states’ problem,” Mitchell said.

In June, the Lower Basin state representatives came up with the proposal now being debated among the basin states, something that initially gave observers hope.

On hand for that presentation was Scott Cameron, the acting assistant secretary for water and science at the Bureau of Reclamation and who has been the federal agency’s voice, while a new commissioner is awaiting confirmation.

He told the Arizona Reconsultation Committee (ARC) during its June meeting, in which the proposal was unveiled, that Secretary of the Interior Doug Burghum is prepared to act if the seven states don’t come up with an agreement by the Nov. 11 deadline.

Acknowledging his role as “watermaster” for the Lower Basin, Burghum is prepared to decide, instead of an agreement, Cameron said. For the Upper Basin, his “tools,” as Cameron put it, are federally funded projects.

The bureau came up with its own alternatives last year, in addition to proposals submitted separately by the upper and lower basin states.

“Our goal is to parachute a seven-state deal” into an environmental impact statement the agency is developing and as the preferred alternative in March, or possibly earlier, in 2026, Cameron told the ARC.

But there are constraints on the timing, according to Cameron, and Congress is on notice that it may be asked to do something. Cameron said the legislatures in Arizona and Colorado may have to lock in that deal, as well.

“We are showing up in force,” Cameron said of his agency, which is creating a negotiating space for the seven states to come up with new ideas, along with federal cash that could be used to seal the deal.

There’s a lot less water in the Colorado system than 50 years ago or even 10 years ago, he said.

“There are real risks” to the upper and lower basin states if something different isn’t done, he said.

Agriculture also must be part of the solution, Cameron added, noting 80% of the water in the basin goes to irrigation.

Cameron also addressed, without naming names, the issue of senior water rights.

California has the most senior water rights in the entire system. Still, it has largely been spared from some of the reductions ordered in the last several years, as water levels at Lake Powell and Lake Mead have dropped precipitously.

Arizona has shouldered the largest share of those cuts; in 2026, due to the hydrology report, its allotment would be reduced by 18%, marking the fifth consecutive year of reductions. Nevada will see a 7% reduction, while California will not have any reduction in its allotment.

“Senior water rights are a wonderful thing, but it does not give you a free pass to ignore what’s going on in the greater community,” Cameron said.

What did the Lower Basin states propose?

It started with the “alternatives” proposal drafted by the Bureau of Reclamation in November under the Biden administration and released in January.

The proposal did not analyze one submitted by the Lower Basin states in late 2024. According to a letter sent to the bureau by the Lower Basin states in February, the federal agency’s proposal had “fatal flaws” — to the point that the Lower Basin states asked the bureau, now under the Trump administration, to retract that proposal.

Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said during the June meeting that a compromise based on the alternatives submitted separately by the upper and lower basin states “is not achievable.”

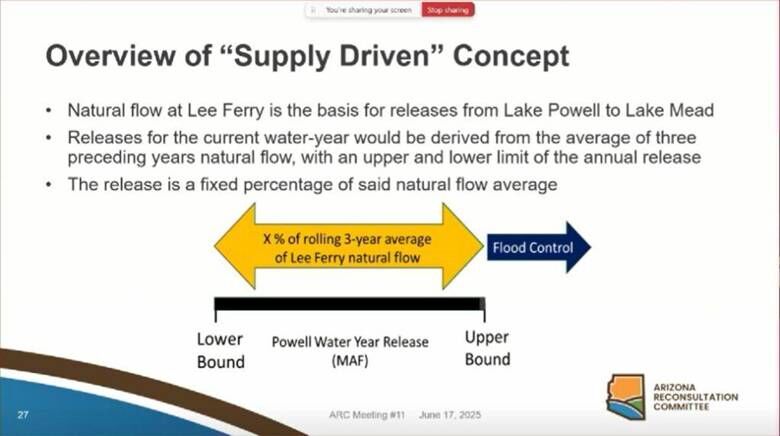

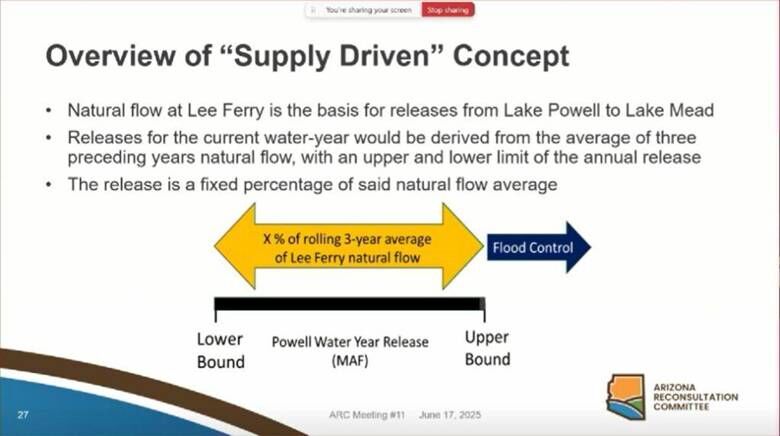

The Arizona proposal is based on a “supply-driven” concept. It requires the seven states to share what’s available in the river, not what’s outlined in the 1922 compact. It maintains an Upper Basin delivery obligation to the lower basin states, although that isn’t quantified.

Each basin would have to take action to live within its respective shares, Buschatzke explained.

“This is a very new thing, focused on what the river provides and finding ways to share that volume,” he said.

The releases from Lake Powell would be based on a fixed percentage of the natural flow of the river, with an upper and lower bound, or limit.

The seven states have agreed to a three-year average, Buschatzke said, although a wide range of percentages is being considered. Over the last 25 years, the average has been 12.4 million acre-feet, far below the 15 million acre-feet provided for in the compact for both the upper and lower basin states.

“This allows for a fair division of what Mother Nature provides to us,” he said.

But the two basin groups are still far from an agreement.

As wide as the Grand Canyon

Buschatzke described the state of the negotiations as “a Grand Canyon’s width apart.”

The most significant sticking point, he said, is the unwillingness for the Upper Basin states to put any mandatory, verifiable reductions on the table. The Lower Basin is willing to put up 1.5 million acre-feet of mandatory, certain and verifiable decreases as part of the deal.

The Upper Basin, he said, has only offered conservation programs that have to be voluntary and paid.

That was the premise behind the Upper Basin’s system conservation pilot program, which has been offered twice in the past decade by the Upper Colorado River Commission.

That’s also what some people refer to as demand management — water conservation that is temporary, voluntary and compensated.

In the most recent iteration of the conservation program, which ended in 2024, the Upper Colorado River Commission spent about $16 million and saved 37,000 acre-feet of water.

Buschatzke said that if the Lower Basin states are going to take mandatory reductions, those changes must be part of a plan to live on a smaller river.

The Upper Basin states also need to contribute in a way to create reductions to live on the same smaller river, he said.

Another sticking point is on percentages or determining what percentage of the water supply moves from Lake Powell to Lake Mead.

On that issue, the two sides are also far apart, he said; the Lower Basin wants a larger percentage, the Upper Basin wants a smaller one.

The third issue is what happens to the upstream reservoirs, starting with Flaming Gorge in Utah.

Buschatzke pointed out that the 1956 act that authorized those reservoirs — which also includes Colorado’s Blue Mesa and Navajo — expressly said the water in those reservoirs is there to meet compact requirements.

“I want to see an equitable sharing of the risk, to make sure neither Lake Powell nor Lake Mead crashes,” he said.

He noted that the 1922 compact, which guides the river’s operations, calls for 75 million acre-feet of water to be released to the Lower Basin states over a 10-year average, plus one-half of the obligation to Mexico, which is approximately 1.5 million acre-feet.

That’s 8.2 million acre-feet of water per year, which he called a tough outcome given the river’s current flow.

The supply-demand proposal would not use those numbers going forward.

Still, Buschatzke said they’re willing to sign off on language that says as long as all states are meeting the terms and conditions of the deal, the Lower Basin territories won’t seek to enforce what the compact requires.

And, he noted, the two groups are meeting regularly to try and come up with a deal.

Mitchell, who is Colorado’s representative on the UCRC and the state’s negotiator on the operating guidelines, is more optimistic that an agreement could be reached before the Nov. 11 deadline.

The search for a consensus-based system

Mitchell told Colorado Politics she’s “100 percent focused on consensus.”

All of the basin states are working diligently to find a deal, she said.

The underlying stress, she explained, is the impact these decisions will have on the 40 million people who call the seven states home.

“I’m optimistic the states can find a consensus-based system that works with the river’s hydrology,” she said, adding the Upper Basin states will continue to advocate for science and modeling as the foundation for any deal.

Mitchell said she hopes their Lower Basin partners understand the risks of system failure, adding no lawyers “will create more water.”

As to the Lower Basin’s proposal, Mitchell said pushing a supply driven approach is different than living with it, and that it would be a difficult decision for the Lower Basin states.

If the percentage creates scenarios that produce what the Lower Basin states are already used to, that’s not a supply-driven approach, she said.

She believes the only way forward is to compromise within the range of what the modeling shows is realistic, and that’s not the historical use of the river, where there isn’t enough water to sustain those historical uses, she said.

Mitchell said she is determined to see an agreement that will succeed, adding she won’t sign onto one that could fail.

“I have to see percentages that protect the river and the system and the 40 million in the basin,” she explained.

The Upper Basin reservoirs are not part of the solution, she added.

Those reservoirs aren’t there to support the Lower Basin, and she said that records of decisions indicate the reservoirs are there for Upper Basin use.

The long-term goal is to reduce the amount of water released from Lake Powell, she said.

Tapping the Upper Basin reservoirs could imply the Lower Basin states don’t have the tools to solve the problem — and Mitchell said she believes they do.

She noted, for example, that Arizona can tap into Colorado River tributaries and also has access to groundwater. Those could be factors in the solution, which “is to look within and not outside,” she said.

“We have to design a plan that works with the realities” of the river, she added.