Divided Colorado Supreme Court upholds disbarment of ex-DA Linda Stanley

The Colorado Supreme Court, by 4-2, upheld the rare disbarment of an elected district attorney on Monday, concluding disciplinary officials correctly barred Linda Stanley from practicing law as a result of her inappropriate comments to the media and her improper attempt to remove a judge from a high-profile murder case.

Voters of the 11th Judicial District in Fremont, Custer, Chaffee and Park counties elected Stanley, a Republican, in 2020. She served one term. Although the Supreme Court concluded Stanley had not, in fact, committed misconduct through her lax oversight of a disorganized prosecution team, the Supreme Court’s majority believed her remaining improprieties merited the most severe sanction available.

“Stanley abused her position as elected DA, seriously impeding the rights of defendants, the right to justice for alleged victims, and the right of Coloradans to adjudicate the guilt or innocence of alleged perpetrators of serious crime,” wrote Justice William W. Hood III in the Sept. 8 opinion.

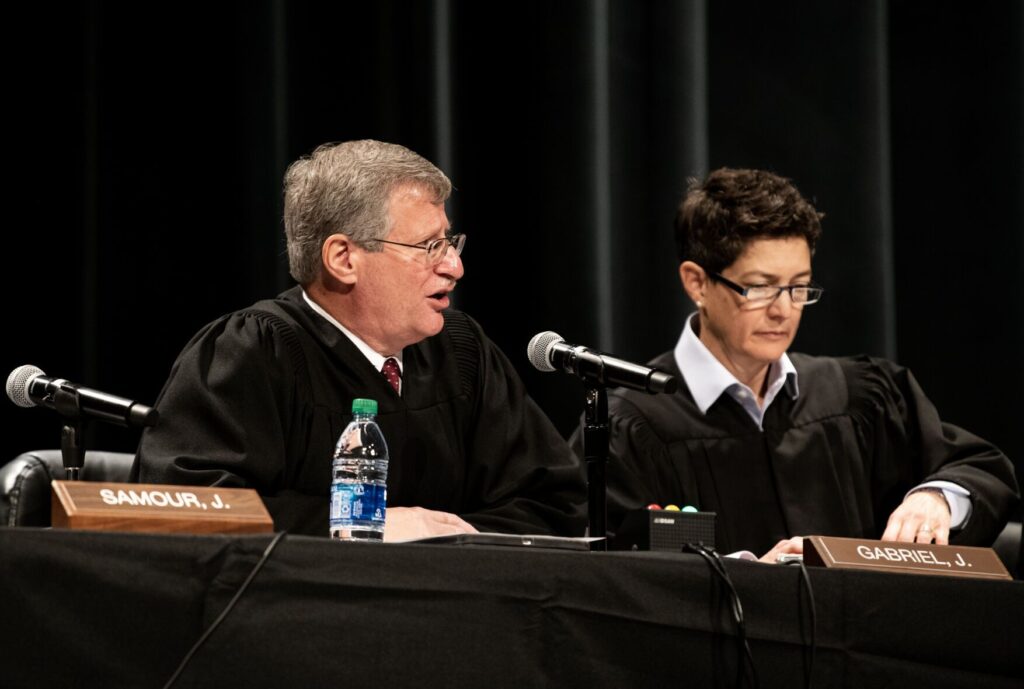

Justice Carlos A. Samour dissented. Although he acknowledged Stanley’s actions “may well deserve” disbarment, he believed another issue prevented the court from even reaching that question: The state’s presiding disciplinary judge should have recused himself from hearing Stanley’s case because he prosecuted her for a different episode of misconduct years earlier.

“Under these circumstances, an objective member of the public could reasonably doubt the PDJ’s impartiality,” wrote Samour for himself and Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez.

In September 2024, a three-member disciplinary panel found Stanley had committed multiple conduct violations and that the appropriate penalty was disbarment, rather than suspension. Much of the decision, including the sanction, split the panel 2-1. Stanley’s charged misconduct encompassed three related categories of behavior.

Barry Morphew prosecution

Soon after taking her seat, Stanley’s office charged Barry Morphew with murdering his wife. The high-profile prosecution had an enormous amount of data from law enforcement. Stanley, who did not have experience with a case of that type, assigned more experienced prosecutors to handle it.

However, the disciplinary proceedings painted a chaotic portrait of the prosecution behind the scenes. Stanley’s office struggled with its obligation to disclose evidence to the defense, she unsuccessfully asked for resources from elsewhere and it became unclear who, if anyone, was actually leading the prosecution team.

For example, one week before the prosecution needed to endorse its expert witnesses, one prosecutor realized no one had begun that task. He sent increasingly more desperate messages to the others, including Stanley, and warned he was going to be “embarrassed” by what the document would look like. Stanley took no action.

The trial judge eventually excluded many of the prosecution’s experts from testifying, finding a pattern of disclosure violations. Stanley’s office eventually dropped the Morphew case before trial.

The Lama inquiry

Shortly before the scheduled trial, Stanley shared with the other prosecutors an online petition calling for the investigation of the trial judge on the Morphew case, Ramsey Lama. The petition alleged Lama’s rulings suggested he had a conflict of interest warranting recusal, and that his ex-wife was an advocate for the victim in the Morphew prosecution.

“Yes let’s go after him!” one prosecutor texted, referring to Lama.

Although Stanley acknowledged at the time that the person who created the petition might not be credible, she asked employees with the sheriff’s office and the Colorado Bureau of Investigation to interview Lama’s ex-wife to see if she would talk about Lama allegedly committing domestic violence. They refused.

Eventually, one of Stanley’s own investigators interviewed Lama’s ex-wife. She denied that he engaged in domestic abuse or acted inappropriately otherwise.

“Bummer,” one of the prosecutors texted in response.

Media statements

Following Morphew’s arrest, Stanley commented on Morphew exercising his constitutional right to silence and appeared on a YouTube program called “Profiling Evil.” In responding to viewer comments, she suggested Morphew could be convicted despite the absence of a body because such convictions had happened elsewhere.

In 2023, she sat down with a KRDO investigative reporter in her office. Although she maintained she could not talk about cases on the record, she proceeded to do so with a camera pointed at her and a microphone clipped to her lapel.

During the interview, she made inflammatory statements about the suspects in the death of a 10-month-old boy. Her comments prompted judges to dismiss the criminal cases and also prompted the leadership of Colorado’s district attorney association to file a misconduct complaint against Stanley.

In the disciplinary panel’s order, the majority –– consisting of Presiding Disciplinary Judge Bryon M. Large and non-attorney Melinda M. Harper –– determined Stanley’s conduct warranted disbarment. They noted Stanley’s attempt to remove Lama from the Morphew case by investigating unsubstantiated domestic violence rumors, on its own, was grounds for disbarment.

The majority found Stanley violated her responsibility to ensure the subordinate prosecutors on the Morphew case abided by the rules of professional conduct and that her investigation into Lama amounted to an abuse of her position. The panel also concluded her various media statements were harmful, and noted two former prosecutors testifying as expert witnesses agreed her comments to KRDO about the defendants were “egregious.”

“Throughout the disciplinary hearing, Respondent never acknowledged that she engaged in wrongful conduct. Nor did she recognize that her actions exhibited poor judgment,” wrote Large and Harper in the majority decision. “Most compelling, however, is that she did not express any awareness of or concern about her conduct’s effect on (the defendants), her prosecution team, the judicial system, or the Coloradans she represents.”

Panel member Sherry A. Caloia, a former elected district attorney for the Ninth Judicial District, dissented in part. She was concerned the majority was “Monday-morning quarterbacking” the Morphew case by holding Stanley responsible for the prosecution’s challenges. She believed Lama had made a “very harsh ruling” against the prosecution and Stanley’s team had tried to comply with its obligations.

Caloia also did not find Stanley’s act of soliciting an interview with Lama’s ex-wife to be a violation. She would have imposed a 2.5-year suspension on Stanley for her remaining violations. Harper also wrote separately to note that she would have found Stanley committed an additional violation for failing to exercise “reasonable diligence and promptness” in the Morphew case.

Stanley appealed the panel’s decision on multiple grounds, ultimately arguing her sanction should be something less than disbarment.

The Supreme Court’s majority agreed the disciplinary panel improperly held Stanley accountable for ensuring her subordinate prosecutors lived up to their own professional obligations in the Morphew case.

“True, Stanley could have, and perhaps should have, done more to guide the team once she became aware of the magnitude of certain problems,” Hood wrote. “But the highly qualified team she put in place also had an obligation to organize themselves effectively and should have been able to navigate the day-to-day challenges presented even by this complex case.”

The majority otherwise upheld the panel’s decision. It also determined Large need not have recused himself as the presiding disciplinary judge because, in his prior role as an attorney regulator, he prosecuted Stanley for her misconduct as a private-practice attorney.

Hood wrote the situation was a “close call,” but that Stanley’s prior case was not “factually connected” to the current one. Moreover, Large abstained from the portion of the decision where Stanley’s prior discipline was taken into account for sanctioning purposes.

Samour, in dissent, believed Large’s partial recusal was not enough, nor was it even authorized. He stressed that he did not think Large was actually biased against Stanley, nor did Large have an obligation to recuse every time he hears a case involving a lawyer he previously prosecuted in his regulation career.

“We live in a cynical world in which parts of the public are skeptical of judges, which means that the perception of impartiality and fairness is more important than ever — certainly, as important as impartiality and fairness themselves,” Samour wrote. But before Stanley’s “livelihood as an attorney in this state is permanently taken away, she’s entitled to a proceeding conducted in front of a tribunal whose impartiality and fairness cannot reasonably be doubted or even questioned.”

Samour would have ordered a new hearing for Stanley.

Justice Brian D. Boatright did not participate in the decision. As is the Supreme Court’s practice, he did not explain his reason for recusing.