Appeals judge decries inability for defendant to challenge his ‘three-strikes’ sentence

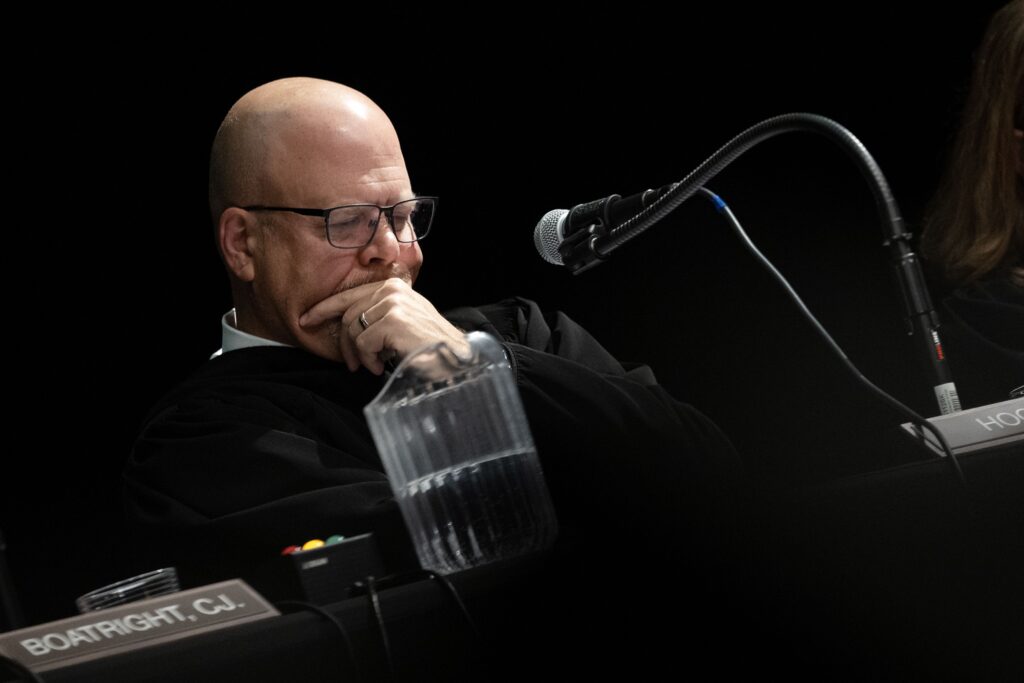

Timothy Hurst/Denver Gazette

A member of Colorado’s second-highest court on Thursday registered his discomfort with a defendant’s inability to challenge his lengthy prison sentence that was a product of the state’s “three strikes” law.

Obdulio Arvelo is serving 48 years in prison for a 2011 theft-related conviction. The sentence resulted from Arvelo’s designation as a “habitual criminal,” meaning he had prior felony convictions that triggered a longer term of incarceration than he would have otherwise received.

Arvelo sought a review of his sentence’s proportionality, arguing that sometime after his conviction, two of his low-level felony offenses had been reclassified to lesser crimes. In an Aug. 14 opinion, a three-judge Court of Appeals panel declined to order a review.

Judge Michael H. Berger wrote separately to agree with that outcome, but also to lament that Arvelo would never be able to seek reconsideration of a sentence that could not have been imposed today.

“Both the district court’s orders and this court’s opinion, which I reluctantly join, reek of some of the absurdities that were comically illustrated more than sixty years ago in Joseph Heller’s novel, Catch-22,” he wrote. While an inquiry into Arvelo’s sentence might find it to be proportional after all, “at least he should have an opportunity to have a court adjudicate such a challenge on the merits.”

Case: People v. Arvelo

Decided: August 14, 2025

Jurisdiction: El Paso County

Ruling: 3-0

Judges: Pax L. Moultrie (author)

W. Eric Kuhn

Michael H. Berger (concurrence)

Under Colorado’s habitual criminal law, a defendant must be sentenced to three or four times the maximum punishment if they have multiple qualifying prior convictions, known as predicate offenses. Because there is a possibility the sentence might be “grossly disproportionate” to the most recent crime — and constitute cruel and unusual punishment — defendants may seek a proportionality review that factors in an offense’s seriousness.

Arvelo’s prior convictions included low-level felonies for theft in 1994, trespass in 2009 and identity theft in 2009. After his 2011 conviction, Arvelo pursued an appeal and then filed multiple motions for postconviction relief. At some point, he argued legislative changes had downgraded two of his felony offenses. Therefore, his 48-year sentence was disproportionate to his crimes.

Multiple times, courts rejected Arvelo’s argument and faulted him for not raising it sooner.

In March 2024, El Paso County District Court Judge Jill Brady rejected Arvelo’s latest petition, deeming it untimely and something he had raised repeatedly and unsuccessfully earlier in his case.

“As a result of this,” Arvelo, representing himself, wrote to the Court of Appeals, “the petitioner has not been afforded any meaningful opportunity from which to be heard as to the merits of his post-conviction claims.”

The appellate panel reached the same conclusion as Brady, rejecting his arguments as belated.

Berger, a retired judge sitting on the panel at the chief justice’s assignment, indicated in his concurrence that he did not minimize the fact of Arvelo’s criminal history when evaluating the almost five-decade sentence.

“At the same time, it is appropriate to observe that these crimes are far from the apex of crimes defined in the criminal code,” he added. “More importantly, it is undisputed that the sentence imposed would have been unlawful if imposed today based on the General Assembly’s intervening amendments to the criminal code.”

Because Arvelo had neglected to challenge the proportionality of his sentence sooner, no court in nearly 15 years had addressed whether his punishment was excessive.

“As a citizen, it seems obvious to me that a court should, once and for all, determine whether his sentence was constitutionally proportionate,” wrote Berger. “But as a judge, I am bound by supreme court rules and precedents, which the court’s opinion correctly apply.”

“I think the legal community should seriously consider how to account for situations like Mr. Arvelo’s,” said defense attorney Heidi Tripp, “where laws have changed and a meaningful review has not occurred as a result of procedural defects. This is especially true when defendants are, often, left to represent themselves after a conviction.”

Earlier this year, lawyers and judges discussed at length the many pitfalls and hurdles that exist for successfully litigating postconviction claims for relief, which have limits on both the types of arguments that can be made and the window for making them.

“It’s deceivingly complicated, and it drives practitioners crazy. It drives judges crazy,” said Denver District Court Judge Eric M. Johnson at the time.

The case is People v. Arvelo.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with additional comment.