Appeals court eases path for injured plaintiffs to appeal unsuccessful claims against government

Colorado’s second-highest court on Thursday clarified that injured plaintiffs have the same opportunity as the government to appeal a judge’s order whenever the claims implicate the immunity afforded to public entities under state law.

The Colorado Governmental Immunity Act broadly shields government entities and employees from lawsuits. There are exceptions, including for emergency vehicle operators who fail to follow the conditions outlined in the law.

A three-judge Court of Appeals panel addressed for the first time the question of what happens when a judge grants immunity to the government, but the plaintiff does not appeal right away because there are claims remaining in the case not involving immunity. In that instance, noted Judge W. Eric Kuhn, the plaintiff can either appeal immediately or at the end of the lawsuit — the same choices the state Supreme Court has recognized when the government is the one appealing.

It “would be unfair to construe the statute as imposing an immediate appeal obligation upon plaintiffs while public entities merely have an option to appeal under the same circumstances,” he wrote in the July 31 opinion.

In the underlying case, Ronald G. Smith was the passenger in a car that collided with a Denver firetruck at the intersection of N. Speer Blvd. and Broadway in 2021. The driver and another passenger died. Smith filed a negligence lawsuit against Denver, the firetruck operator and the company that manufactured the system enabling emergency vehicles to turn traffic lights green upon approach.

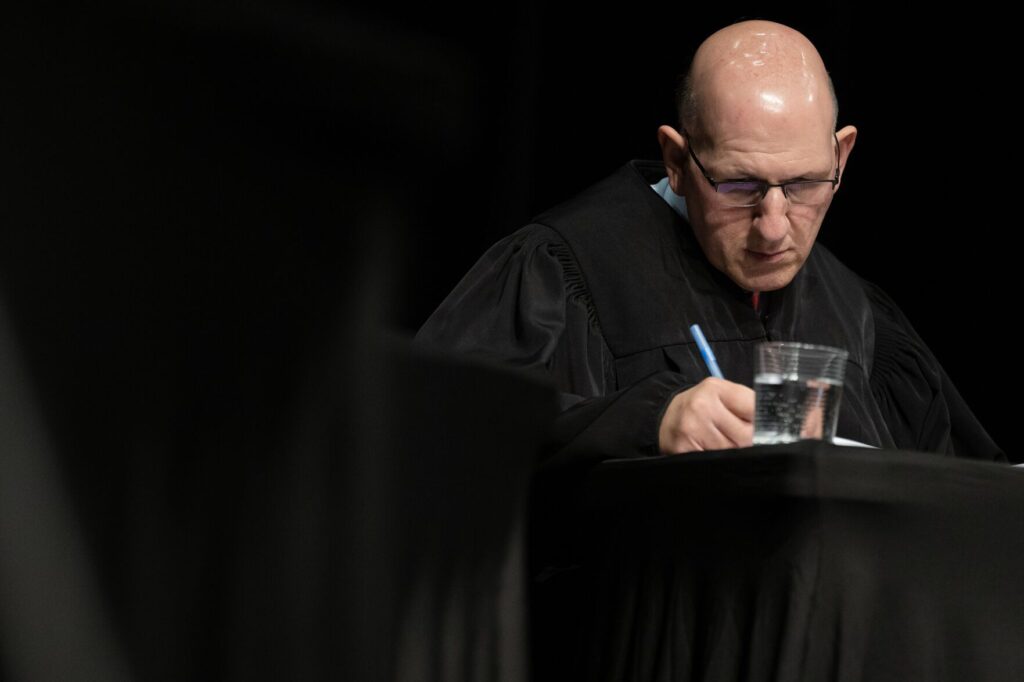

The city and the operator argued they were entitled to immunity because the firetruck appropriately entered the intersection in compliance with the law at the time of the accident. Denver District Court Judge Jon J. Olafson agreed the firetruck’s handling was “consistent with safe operations to proceed against a red light” and he dismissed the claims against the Denver defendants.

More than one month later, Olafson dismissed the remaining claims against the manufacturer of the traffic light technology at the request of the parties.

Smith then appealed Olafson’s governmental immunity decision. In response, the Denver City Attorney’s Office argued the Court of Appeals could not hear the case because Smith had waited too long.

Specifically, the Colorado Governmental Immunity Act provides that a judge’s decision on a motion to dismiss “shall be subject” to interlocutory — or mid-case — appeal. Smith did not appeal Olafson’s original order immediately, but instead moved to appeal after Olafson ended the remaining claims against the non-government defendant.

In arguing Smith should have appealed Olafson’s original order right away, Denver cited a 1998 Court of Appeals opinion that held a group of plaintiffs was required to appeal an immunity order immediately, rather than waiting for the case to conclude years later.

Smith countered by pointing to a Colorado Supreme Court decision issued months later concluding a government defendant that is denied immunity need not appeal immediately. Instead, it can also appeal the immunity order along with other issues at the conclusion of a case.

The appellate panel in Smith’s case analyzed whether the Supreme Court’s holding applied equally to plaintiffs appealing an immunity decision as it did to defendants appealing an immunity decision. The panel answered in the affirmative, meaning Smith was within his rights to appeal after all claims had been terminated.

The panel ultimately agreed with Olafson’s conclusion that Denver and the firetruck operator were entitled to immunity on Smith’s claims.

The case is Smith et al. v. City and County of Denver et al.