Colorado Supreme Court weighs time to sue for minimum wage violations in absence of directive

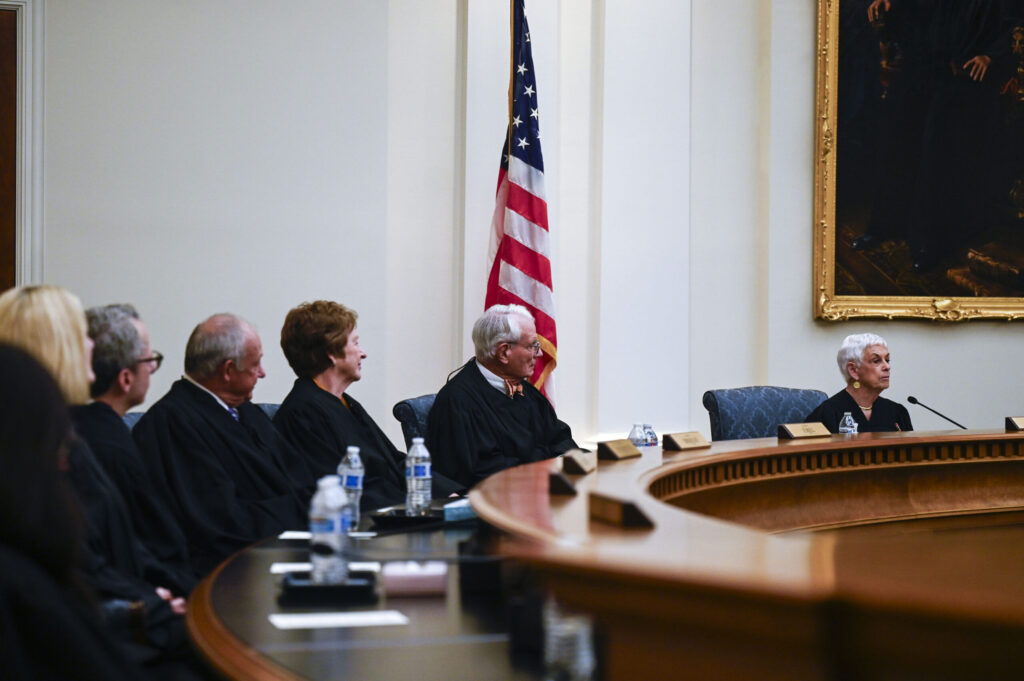

With the state’s minimum wage law silent on the subject, the Colorado Supreme Court attempted to figure out on Tuesday how much time workers have to file claims against their employers.

There were seemingly two options: Up to three years from the violation, as is the case for claims under the neighboring Colorado Wage Claim Act; or six years, which is the catch-all window for recovering a debt. By 2-1, the state’s Court of Appeals previously ruled the six-year statute of limitations applies.

“The Minimum Wage Act and the Wage Claim Act are part of the same statutory scheme. They address the same issue, and that is payment of wages to Colorado workers,” said attorney Veronica T. Hunter during oral arguments, advocating for the shorter statute of limitations to apply. “The result of applying a different statute of limitations results in a sort of regulatory bait-and-switch.”

“All of what you said from a policy perspective resonates with me,” said Justice William W. Hood III. “I guess what I struggle with is, why did the legislature not make this more clear?”

Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. did not attend the arguments, and Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez said he will “not be participating in this case.” Consistent with the Supreme Court’s practice of not disclosing reasons for its members’ recusals, it was unclear why Samour had stopped participating. It was also unclear when he recused, as none of the court’s orders in the case to date indicated any abstentions.

In the underlying case, Samuel Perez filed a proposed class action lawsuit against his employer, By the Rockies, LLC, for allegedly refusing to pay its Carl’s Jr. employees for required breaks. Perez sued in 2022, despite having left his job in 2017. After looking at competing legal interpretations by federal judges in recent years, an Arapahoe County judge dismissed the case, persuaded that Perez needed to file within two or three years of the violation.

However, a Court of Appeals panel noted the Colorado Wage Claim Act explicitly includes a two- or three-year statute of limitations, but lawmakers omitted similar language from the Minimum Wage Act. Therefore, the catch-all six-year window applied for raising alleged minimum wage violations.

Judge Neeti V. Pawar, who authored the majority opinion for herself and then-Judge David Furman, observed during oral arguments there may be valid reasons to treat claims for unpaid minimum wages differently than other wage violations.

“If somebody doesn’t get paid on the day they don’t get their rest break, they’re not gonna file a claim for $1.12,” she said. “Doesn’t it seem like six years would make more sense in order for the accrual of the claim itself to have some value?”

Judge Terry Fox dissented, writing that the majority’s interpretation drove a wedge not only between the two wage laws, but between Colorado law and its federal counterpart.

By the Rockies appealed to the Supreme Court, supported by outside business entities. The national and state chambers of commerce noted a six-year statute of limitations was inconsistent with the three-year recordkeeping requirement for employers.

“Sometimes the simple answer is also the right answer,” added attorneys for the state’s hotel and restaurant trade associations. “Rather than try to make the statute of limitations for claims arising under the Minimum Wage Act different from the statute of limitations for claims arising under the Wage Claim Act, the simplest and clearest solution is that they should be the same.”

Brian D. Gonzales, representing Perez, argued to the justices that the state’s two wage laws did not cover identical subject matter.

“This entire statutory scheme was intended to protect employees and the legislature has been absolutely clear that is the goal,” he said, advocating for the six-year window. “Any ambiguity should be interpreted in favor of the employee.”

Hood wondered if it would be prudent to “go to the default statute of limitations and let the General Assembly clean it up if they want to.”

And yet, “there’s no legislative intent that says if the statute is silent, we adopt a catch-all,” said Justice Richard L. Gabriel.

The case is By the Rockies, LLC et al. v. Perez.

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: