Colorado Supreme Court finds defendant deprived of chance to testify about lawyer’s advice

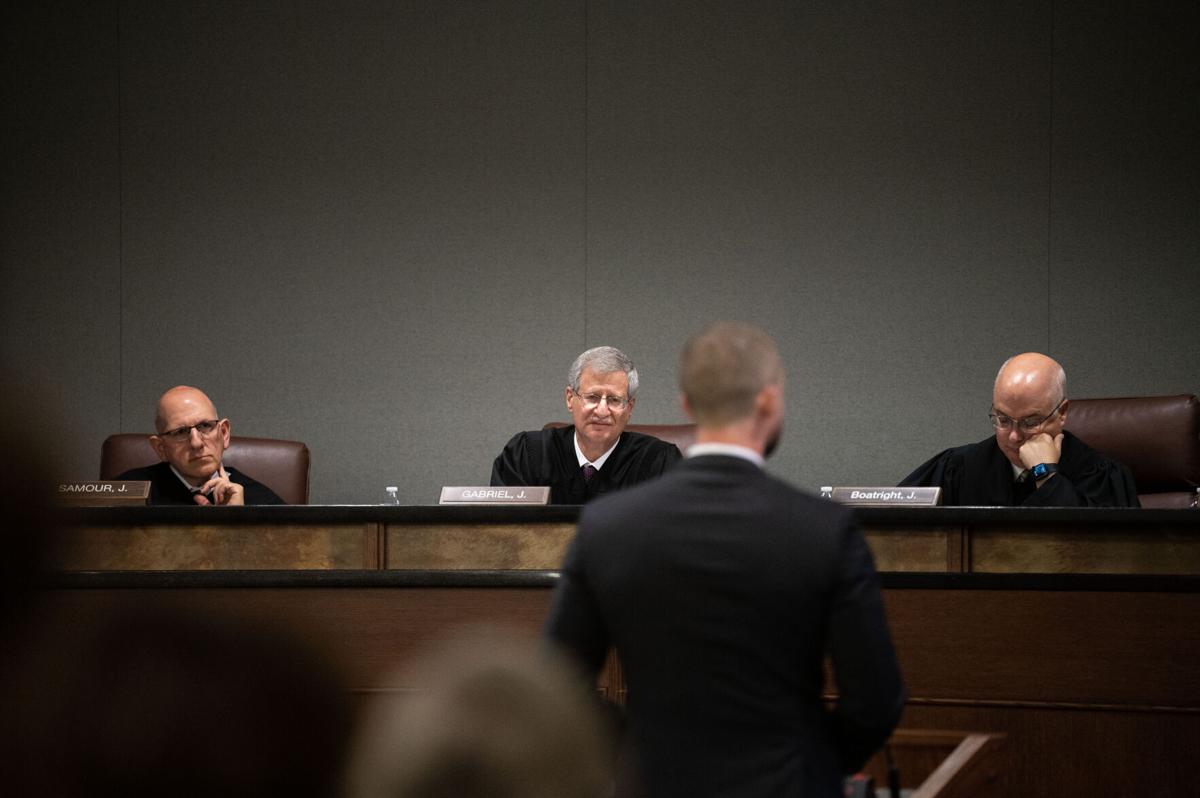

FILE PHOTO: Colorado Supreme Court Justices (from left) Carlos A. Samour Jr., Richard L. Gabriel and Brian D. Boatright listen to arguments from Jake Davis, an attorney in the Nonhuman Rights Project v. Cheyenne Mountain Zoological Society case, as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Stephen Swofford/Denver Gazette

The Colorado Supreme Court agreed on Monday that a man serving a lengthy prison sentence for securities fraud should receive a new trial after he was prohibited from testifying about what information his lawyer advised him to disclose to investors.

Kelly James Schnorenberg contended he did not commit securities fraud because he consulted with an attorney who advised him what “material facts” he needed to disclose about his prior business troubles. Because the lawyer was unavailable to appear at his criminal trial, Schnorenberg attempted to testify about the advice himself, only for the prosecution to object and for the trial judge to bar the evidence.

The Court of Appeals believed a new trial was warranted. The Supreme Court upheld that conclusion, noting the evidence could have cast doubt on whether Schnorenberg acted willfully in withholding information, as is required for a criminal violation.

“Schnorenberg was unable to testify as to what his lawyer had actually advised him, which limited his ability to argue that he lacked the required mental state,” wrote Justice Richard L. Gabriel in the June 23 opinion. “Because this evidence was central to Schnorenberg’s defense, we conclude that there is a reasonable probability that the exclusion of this testimony contributed to Schnorenberg’s convictions.”

Schnorenberg raised in excess of $15 million from hundreds of investors for an insurance marketing venture. He failed to disclose that he was barred from selling securities in Colorado, had not paid his earlier investors, carried large debt loads in his companies and had outstanding civil judgments against him, among other things.

Prosecutors charged Schnorenberg with more than two dozen counts of securities fraud. Douglas County jurors convicted him and he received a prison sentence of 76 years and an order to pay nearly $14 million in restitution.

In 2023, the Court of Appeals vacated seven of Schnorenberg’s convictions for being brought outside the statute of limitations — which the government did not dispute. However, the three-judge appellate panel also reversed the remaining convictions based on an error at trial.

Former District Court Judge Paul A. King refused to allow Schnorenberg to testify about the advice he allegedly received from his lawyer that Schnorenberg did not have to disclose key pieces of information to investors.

Although Schnorenberg was able to testify narrowly that he received advice on certain topics, King believed the remaining information called for a hearsay response — meaning a statement made out of court that is being used to prove the truth. King also rejected the defense’s attempt to instruct the jury that it may consider evidence of Schnorenberg’s “good faith reliance on the advice of counsel.”

The appeals panel concluded Schnorenberg should have been allowed to speak about the alleged advice, as it could have proven Schnorenberg did not have the mental state required to commit the crimes.

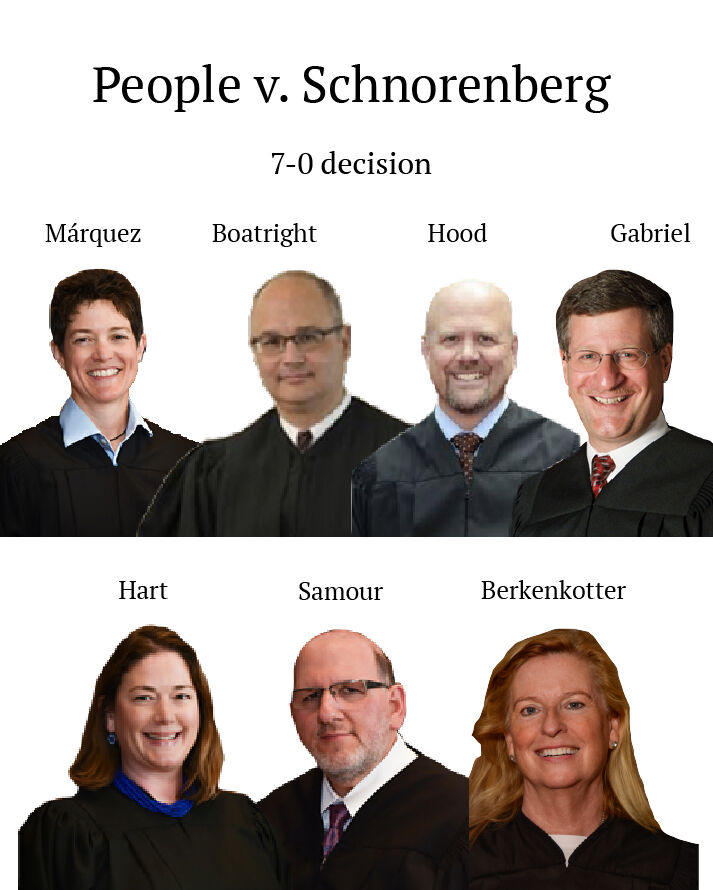

Members of the Colorado Supreme Court during a "Courts in the Community" visit to Falcon High School in Peyton, Colo. on May 15, 2025. From left to right: Justices Carlos A. Samour Jr. and Richard L. Gabriel, Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez, and Justices William W. Hood III, Melissa Hart, Brian D. Boatright and Maria E. Berkenkotter.

Michael Karlik michael.karlik@coloradopolitics.com

The Colorado Attorney General’s Office appealed, arguing the lawyer’s alleged advice would have illustrated Schnorenberg’s intent, but the law does not require someone to intend to defraud investors.

Attorney Lynn C. Hartfield, representing Schnorenberg, pointed out it is not a crime to misstate or omit facts to investors. Only material, or important, misstatements or omissions lead to criminal liability, which was the factor Schnorenberg’s testimony sought to illuminate.

“What innovator would risk entering the market if they had to guess at whether they might go to prison for 76 years for failing to disclose something, even if their lawyer advised them they didn’t need to?” she said at oral arguments.

“He was selling securities and was banned from selling securities and didn’t tell anyone that he was banned from selling securities,” countered Senior Assistant Attorney General Trina K. Kissel. “One does not need to consult a lawyer to know that is a material misstatement or a material omission.”

Ultimately, the Supreme Court determined prosecutors needed to prove Schnorenberg willfully omitted or misstated material information to investors. Relying on counsel’s advice about what is material, Gabriel wrote, could lead a jury to conclude any violation was not willful. He also suggested the government’s own actions at trial contributed to the need for Schnorenberg to offer his own account of the legal advice.

“We are unwilling to lay sole blame on Schnorenberg for his securities counsel’s unavailability,” Gabriel added, because the prosecution “objected to a continuance that would have allowed securities counsel to appear.”

The court agreed a new trial was warranted.

The case is People v. Schnorenberg.

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: