Colorado Supreme Court reaches consensus on stalled racial bias rule, with heavy revisions

The Colorado Supreme Court notified a small group of lawyers and judges last week that it has tentatively agreed on a new rule addressing racial bias in jury selection for criminal trials, breaking its yearslong silence on the proposed reform.

Most prominently, the court’s proposed path forward would no longer designate certain justifications for removing jurors of color as off-limits by default. Instead, trial judges will simply consider “any relevant circumstances” when deciding if a juror is being unconstitutionally dismissed because of their race.

In February 2023, the Supreme Court held a lengthy public hearing on a draft rule change that would make it more difficult to remove, or strike, jurors of color from criminal trials for reasons that, while not explicitly racial, may still correlate with their race. But 841 days later, the justices had taken no action — an abnormally long silence in the wake of a hearing.

Then, on May 29, Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr. sent a letter to the Rules of Criminal Procedure Committee, an advisory body that drafted the proposed racial bias rule. Samour, who is the Supreme Court’s liaison to the committee, included a heavily revised version of the racial bias proposal, which he shared with Colorado Politics upon request.

“I’m delighted to inform you that we were able to reach consensus,” he wrote. “Having had discussions now among the seven of us that no doubt mirror some of yours we understand just how challenging this must have been for your committee.”

Months of uncertainty

Nearly 40 years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized in Batson v. Kentucky that purposeful racial discrimination in jury selection was unconstitutional. Now, if a party — typically the prosecution — strikes a juror of color, the defense may raise a “Batson challenge,” forcing the prosecutor to justify the dismissal with a “race-neutral” reason.

The original proposed change to criminal Rule 24 aimed to reduce less obvious forms of exclusion that are not explicitly linked to a person’s race — for example, dismissing a juror of color for expressing distrust of police, living in a “high-crime neighborhood,” or having prior contact with law enforcement. The rule would have also created restrictions on removing jurors for their demeanor — like when an El Paso County prosecutor dismissed a Black woman who allegedly had a “sour look on her face.”

After a group of Democratic state lawmakers failed to enact changes legislatively in the face of opposition from district attorneys, the Colorado Supreme Court’s criminal rules committee — which consists of prosecutors, defense lawyers and judges — produced the draft racial bias rule. District attorneys once again voiced opposition, deriding it as “affirmative action in jury selection” and warning that prosecutors could be afraid to strike jurors of color. Defense attorneys and some trial judges countered with their own examples of bias under the current system.

The Supreme Court took no immediate action on the Rule 24 change following the February 2023 hearing. Samour assured the rules committee that because the court was currently considering three cases involving Batson challenges, the justices would turn to the rule after resolving those appeals.

However, the decisions in the three racial bias cases suggested the Supreme Court was preparing to drastically scale down the Rule 24 proposal — if not reject it entirely.

The Samour letter

Last year, the Supreme Court decided prosecutors could use a juror of color’s distrust of police as a reason for dismissing them, and also rejected the idea that demeanor-based dismissals required corroboration from others in the courtroom. Both were key components of the proposed racial bias rule.

In fact, the Supreme Court appeared to coalesce around a different solution: Asking the legislature to abolish “peremptory strikes,” which are the mechanism by which parties can dismiss jurors without a reason in the first place, unless there is a Batson challenge.

Then came Samour’s letter.

“Please be assured that the court considered your proposal carefully over multiple lengthy discussions, some of which were appropriately spirited,” he wrote to the criminal rules committee. He attributed the delay to the three Batson-related cases decided last year and confirmed his court had “preliminarily agreed upon” new language.

“We recognize that what we came up with is different from your proposal,” Samour elaborated. He contended the rule as originally proposed “deviates” from the U.S. Supreme Court’s Batson decision — even though the Washington Supreme Court adopted a similar rule nearly a decade ago.

“Therefore, in the end, we feel duty bound to remain faithful to Batson,” Samour wrote.

He also explained that Court of Appeals Judge Elizabeth L. Harris, who chairs the rules panel, suggested the state Supreme Court allow the committee two weeks to respond to the new version of the racial bias rule. Therefore, Samour asked for the committee’s thoughts by the end of June 13.

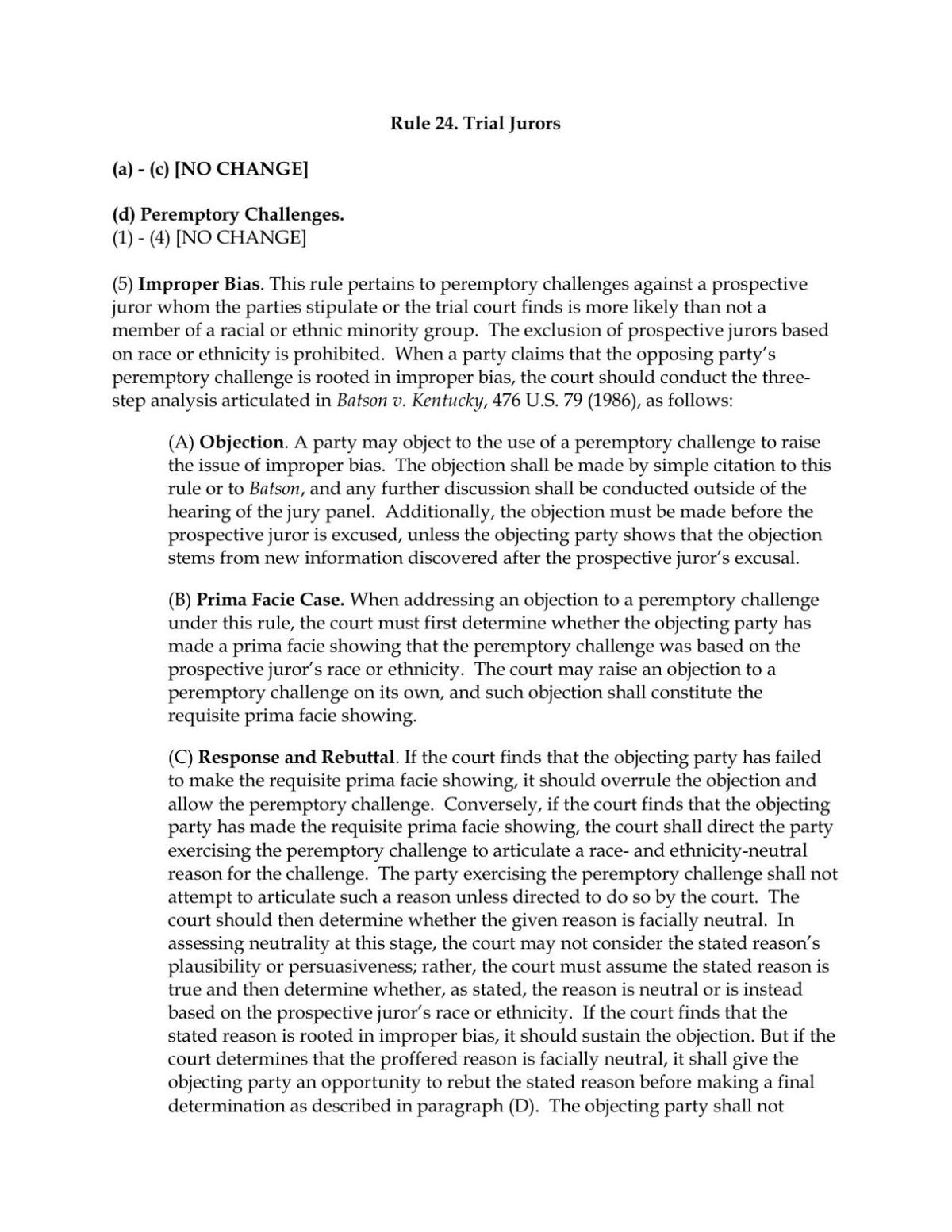

The Supreme Court’s revisions notably provide detailed instructions to trial judges about handling Batson challenges. For example, the proposed rule now clarifies that Batson challenges apply to jurors “whom the parties stipulate or the trial court finds is more likely than not” a person of color. The rule also advises trial participants to respect each distinct step of the challenge — raising a plausible objection, providing a race-neutral reason and explaining the ruling on the record.

The original proposal referenced reasons that were “presumptively invalid” for striking a juror of color, such as contact with police or distrust of law enforcement. Although the new proposal deems those “relevant circumstances,” the Supreme Court now suggests those justifications pose a problem only when they “might be disproportionately associated with race or ethnicity.”

Finally, rather than requiring demeanor-based strikes to have corroboration from the judge or the other side, corroboration of the juror’s behavior is only a factor to consider.

The Supreme Court could adopt the original draft “and make clear that implicit bias has no place in the jury selection process and ensure that our juries better reflect the diversity of our communities,” said James Karbach of the Office of the State Public Defender. Instead, the Supreme Court’s proposal “explicitly allows prospective jurors to be excluded from jury service as long as racial basis was only a partial and not a substantial motivating factor in their removal. Colorado can and should do better.”

He added that the office urges “everyone, including the courts and the legislature” to take action on racial discrimination in jury selection.

“We are deeply disappointed by the court’s letter. The court can, in fact, approve proposed rules that are more protective of nondiscriminatory jury selection than the federal standard — and it should have done so,” said Emma Mclean-Riggs, senior staff attorney with the ACLU of Colorado. “The court’s proposed language rejects the most powerful accountability measures proposed by the committee.”

In contrast, Boulder County District Attorney Michael Dougherty, who objected to the original proposal as “too broad,” said the new language is acceptable.

“As Justice Samour notes in his letter to the committee, the Colorado Supreme Court’s proposed revisions to Rule 24 adhere to Batson and decades of Colorado jurisprudence,” he said. “At the same time, however, they succinctly summarize Batson‘s test and describe how it could be applied to account for implicit bias. This appropriately balances the need to address implicit bias against the valid concerns expressed about the committee’s proposed amendments.”

Through the judicial branch, Colorado Politics asked Samour why the Supreme Court was only inviting the criminal rules committee to provide feedback on the substantially revised proposal, and not reopening the public comment period.

“The public has already provided input,” Samour wrote, “both through written comments and at a public hearing. And the supreme court gave serious consideration to that input.”

This article has been updated with additional comments.

Colorado Politics Must-Reads: