Lakewood police acted unconstitutionally in using drug detection dog, Supreme Court rules by 5-2

Lakewood police violated the constitutional prohibition on unreasonable searches by ensuring a driver’s door remained open so a drug detection dog could sniff inside the vehicle without probable cause, the Colorado Supreme Court concluded on Monday.

In the 5-2 decision, all justices agreed with the principle that law enforcement conducts a search if they “facilitate” a dog’s entry into a vehicle. However, the majority took a different view of defendant Tien Dinh Pham’s traffic stop than the dissenting justices did.

Justice Richard L. Gabriel, narrating the majority’s perspective of the body-worn camera footage, emphasized that Agent Kyle Winters directed Pham out of the vehicle for a suspected traffic violation, then quickly moved Pham away from the car before Pham could close the driver door. As a result of Winters’ actions, detection dog Duke was able to put his paws and face inside the vehicle and alert to drugs.

“This was not a scenario in which the officers merely left a door open so that the dog could get a better sniff of the ambient air,” Gabriel wrote in the Feb. 3 opinion. “Rather, the record reflects, and the trial court properly found, that, through their own actions, the officers facilitated the dog’s entry into Pham’s vehicle so that the dog could sniff inside.”

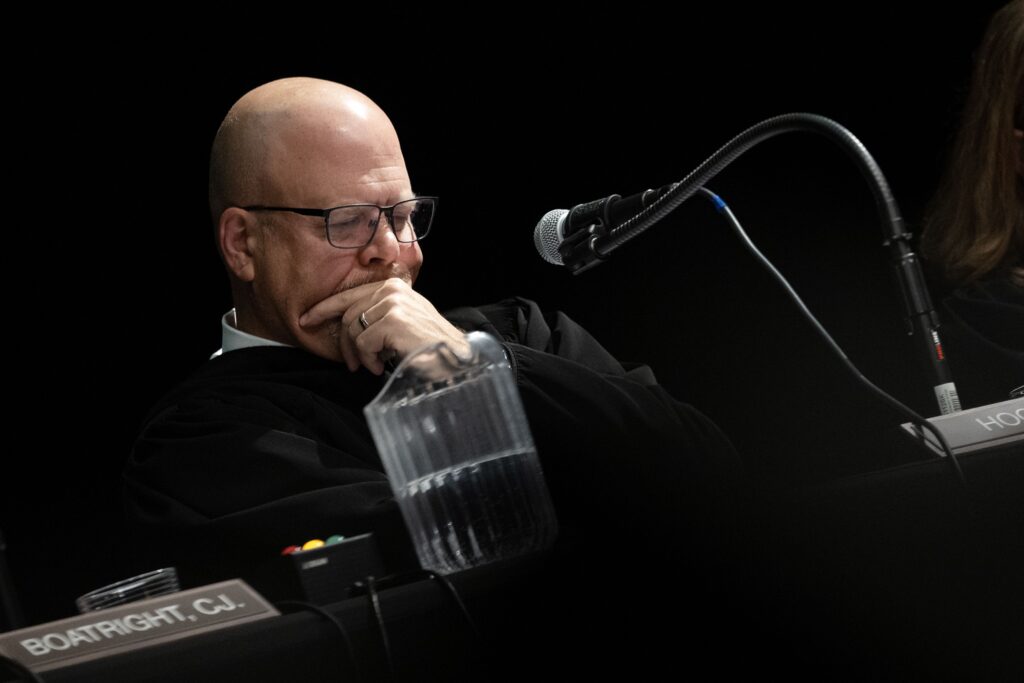

Justice Brian D. Boatright, writing for himself and Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez, faulted Pham for not closing the door to his vehicle. In Boatright’s view, the police did not facilitate Duke’s entry. Rather, they simply declined to close the already-open door.

“Leaving the door open, even if it was to give the dog a better sniff, does not violate the Constitution,” Boatright argued. “No constitutional right requires an agent to close a vehicle’s door after it has been left open by its occupant.”

In the underlying case, Pham stands accused of numerous criminal charges related to drug and weapons possession. Winters had been stationed in a “high-crime area” and began following Pham’s vehicle based on an apparent hunch. After Pham allegedly committed a traffic infraction, Winters pulled him over.

Winters decided he wanted Duke to sniff around Pham’s vehicle. Although there were differing interpretations of what happened next, Winters ordered Pham out of the vehicle and placed his hand on the doorframe. Another Lakewood police agent patted down Pham and they directed Pham to stand elsewhere.

Winters then retrieved Duke and walked the dog around Pham’s car. Winters manipulated the driver door so Duke could navigate around an obstacle, but the door stayed open. Duke placed his front paws on the driver seat and stuck his head in the vehicle, where he alerted to drugs. Officers subsequently recovered multiple types of narcotics from the car.

Source: People v. Pham

The defense moved to exclude the evidence from trial, alleging a violation of Pham’s Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches. Jefferson County District Court Judge Tamara S. Russell sided with Pham on two grounds. First, she believed Winters had unlawfully asked Pham to exit the car. Second, Winters facilitated Duke’s sniff inside the vehicle without probable cause of any crime beyond the alleged traffic infraction.

“For me, the stop is fine. The ticket is fine. For me, even — sure, even pulling him out of the car, if there’s a reason,” Russell said. But Winters left the door open “on purpose” so Duke could sniff inside.

“The police officers knew what they were doing,” she added.

The prosecution appealed directly to the Supreme Court. The justices agreed Rusell’s first conclusion was faulty, as longstanding U.S. Supreme Court precedent allows police officers to order a driver out of a vehicle for safety reasons during a traffic stop.

As for the dog sniff, Gabriel pointed to a 2014 decision of the Denver-based U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, in which law enforcement ordered the occupants out of a vehicle, prevented a door from closing and let a drug detection dog jump into the car to sniff. The panel of appellate judges — which included now-U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch — found it problematic that the officers “created the opportunity for a drug dog to go” where they could not.

Because probable cause for a crime did not surface until after Winters facilitated Duke’s sniff inside the vehicle, Gabriel concluded Russell correctly barred prosecutors from using the evidence from the unconstitutional search.

Boatright criticized the majority for characterizing Winters’ conduct as “facilitation.”

“Apparently, not closing the defendant’s door amounts to unlawful conduct,” he wrote. “This standard is unlike any other I am aware of in the country.”

Boatright would have found no constitutional violation, adding that police did not do anything to encourage Duke to go inside the vehicle other than declining to close the driver door.

The case is People v. Pham.