Colorado lawmakers suggest chief justice’s request for new judges may be nonstarter

Some members of the legislature’s powerful budget committee cautioned Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez on Tuesday that it would be difficult to justify a spending increase for new judgeships in light of substantial cuts to be made elsewhere.

Márquez appeared before the Joint Budget Committee to field questions about the Judicial Department’s $813.2 million budget request for the upcoming fiscal year. The top priority, she said, was the creation of 29 new judgeships over a two-year period. The total cost, including associated staff, would exceed $20 million annually.

“What our judges need right now, particularly in districts where they’re feeling quite overwhelmed — they need hope. They just need hope that relief is coming,” said Márquez, adding that the judiciary would remain understaffed even if lawmakers approved the request.

“We’re beginning to lose judges who are choosing to leave because of workload overwhelm. We are starting to backslide in recent gains among diversity of our bench and we’re seeing an unfortunate drop-off in applications for judicial vacancies,” she continued. “This does not bode well for the future of our judiciary.”

In response, Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Brighton, described at length how the roughly $672 million budget deficit facing the state would make it impossible to entertain any new spending.

“We can’t afford any of it,” she said. “You have said several times you wish to be good partners. Well, from my perspective, being a good partner is: you need to help us find where we’re gonna make cuts. Certainly not make increases.”

Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Weld County, one of the sponsors of the deal that will remove two ballot measures from the November ballot, talks to reporters after the conclusion of the 2024 special session. From left to right behind her, Sen. Byron Pelton, R-Sterling; Sen. Larry Liston, R-Colorado Springs and Sen. Kevin Van Winkle, R-Highlands Ranch.

Sen. Judy Amabile, D-Boulder, added that she was interested in “having a viable court system. But also, this feels like a whole lot all at once.”

Rep. Shannon Bird, D-Westminster, the vice chair of the committee, attempted to walk back the bleak predictions. She cautioned that the committee would ultimately determine financial priorities.

“There isn’t zero money. There is money to make sure we’re doing right by the citizens of Colorado,” Bird said.

A request years in the making

The judiciary’s request for new judges is based on a recent set of workload studies. The increase is largely focused on the trial courts, including a second judge added to Denver’s separate probate court, four district judges added to the Fourth Judicial District of El Paso and Teller counties, and a second judge added to the La Plata County Court, which has had only one full-time judge since 1978.

There would also be three judges added to the 22-member Court of Appeals, which handles cases in three-judge panels and last received an expansion nearly two decades ago.

On Wednesday, Sens. Dylan Roberts, D-Summit County, and Lisa Frizell, R-Castle Rock, introduced standalone legislation to implement the increases.

In written responses to legislators ahead of the Joint Budget Committee hearing, the Judicial Department defended its request for additional judges. It noted the department’s budget has increased at a lesser rate since fiscal year 2019-2020 than other state agencies and it had held off on seeking new judgeships for some time.

Moreover, the “overwhelming majority of the work of Courts and Probation is driven by decisions made by the General Assembly,” the department argued.

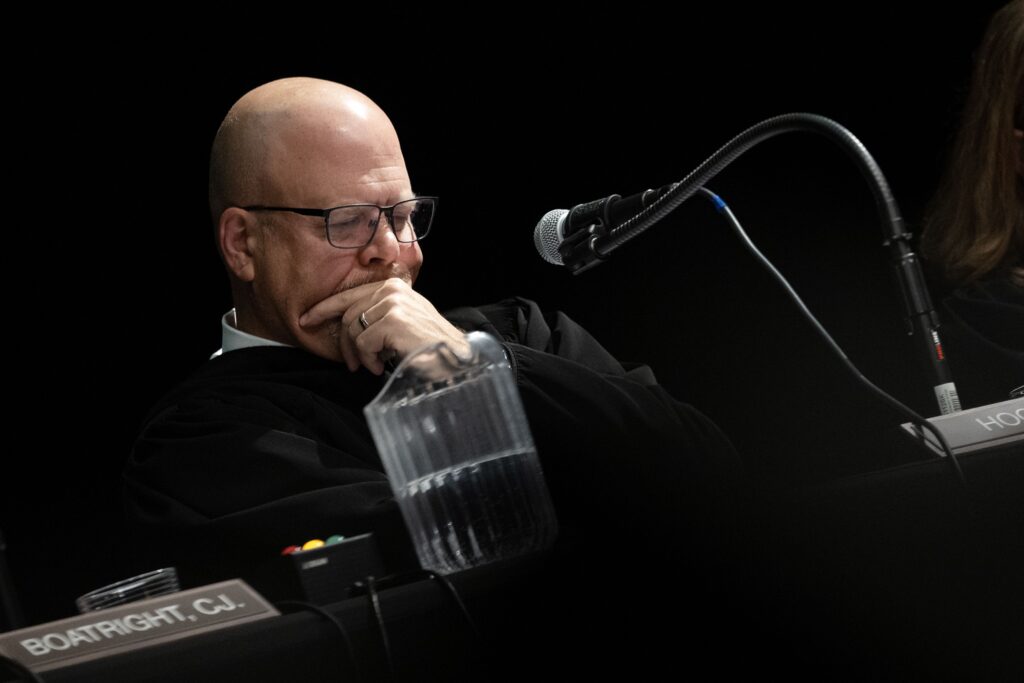

(From left) Colorado Supreme Court Justice Brian D. Boatright, Chief Justice Monica M. Márquez and Justice William W. Hood III listen to arguments from Assistant Attorney General Caitlin E. Grant during the People v. Rodriguez-Morelos case as part of Courts in the Community at the Wolf Law building at University of Colorado Boulder on Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. The semi-annual event entails the Colorado Supreme Court hearing arguments before an audience of students throughout the state. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

To make the case to lawmakers, Márquez enlisted Chief Judge Michelle Amico of the 18th Judicial District, which is the most populous jurisdiction until next week, when it will consist solely of Arapahoe County in a long-planned reorganization into two districts.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say we’re barely keeping our heads above water. And some of my colleagues would actually sit before you and tell you they are drowning,” she said.

Echoing Márquez’s concerns, Amico disclosed one Arapahoe County judge quit last year because their docket was too overwhelming.

Amico described the typical day of a domestic relations judge, who may spend six hours in the courtroom hearing two spouses present evidence in a divorce case. Then, the judge may turn to several emergency motions in other cases. They could also spend time drafting orders, such that they do not have time to address the divorce immediately. Meanwhile, the spouses, not having received a quick decision, may deluge the docket with additional filings.

Further, Amico said trial judges frequently address time-sensitive matters like temporary protection orders — also known as restraining orders — and emergency guardianship or conservatorship petitions.

“We are experiencing so many people who are facing mental health challenges … there’s been an increase in those folks all across our docket types. It’s really a societal problem we all need to do a better job at addressing and we are doing our level best to be creative,” she continued. But “our ability to be creative and innovative goes to the bottom of the list when all we’re focusing on, day in and day out, is the work coming in the door.”

Some lawmakers wondered whether it was feasible to specifically add judges to handle domestic relations cases, or whether more criminal judges would necessarily require funding for additional public defenders or prosecutors. Others shied away from the notion of any new allocations of money.

“I respect the fact that you’ve kept your budget so tight over a long period of time,” said Rep. Rick Taggart, R-Grand Junction. “My worry is this number alone is large.”

Lisa Feret, D- Arvada, holds her daughter Elizabeth Carmen, at her desk on the first day of the 2025 legislative session at the State Capitol on Wednesday, Jan. 8, 2025. (Stephen Swofford, Denver Gazette)

Other needs

Also during the hearing, Márquez touched upon the need for new courtroom technology. The department’s written responses elaborated that judges currently rely on three separate systems for holding virtual proceedings, creating transcriptions and live streaming to the public. The judiciary is seeking a new platform that integrates those features and fixes the shortcomings of the current virtual court software, Webex.

Cisco, the owner of Webex, has “focused on enhancing Webex as a collaborative meeting tool, introducing features suitable for office settings but detrimental to the courtroom environment (e.g., reaction emojis, public-only chat, and simplified controls that cannot be easily customized by role),” the department wrote. But “rather than partnering with the Department to adjust these features for judicial purposes, Cisco encourages changing our processes — such as not posting public links or employing complex scheduling steps. … These efforts increase administrative overhead and do not align with the Department’s operational realities.”

Márquez also responded to a proposal from Joint Budget Committee staff to eliminate $3 million from a grant program designed to fund courthouse improvements in low-income counties. She asked that any cuts last for one year only, and cited a recent fire in Conejos County that forced the courthouse to relocate to a fire district building.

“They’re using folding tables, they’re using Walmart sheets, they’re using an unheated space that still holds the fire truck every night. That current situation long-term is unsustainable,” Márquez said. “Permanently eliminating that funding or taking any action that would jeopardize the solvency of those funds long-term would have devastating impacts on our rural communities.”