Colorado’s federal judges give themselves increased disciplinary power over attorneys

The judges of Colorado’s federal trial court have voted to give themselves the power to refer lawyers for discipline — potentially resulting in suspension or disbarment — simply for violating individual courtroom protocols.

Without explanation, the U.S. District Court amended its local rules effective Dec. 1 to permit judges to impose “additional standards of professional conduct” beyond those contained in the rules of conduct governing the legal profession in Colorado.

Previously, Colorado Politics reported that none of the other district courts falling within the jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit has adopted such a broad grant of power for its judges.

Attorney Matthew Skeen, U.S. District Court Judges Gordon P. Gallagher and S. Kato Crews, retired U.S. Magistrate Judge Kristen L. Mix and attorney Kevin Homiak speak on a panel about pro bono opportunities for lawyers at Colorado’s federal trial court on May 8, 2024.

Former U.S. Magistrate Judge Kristen L. Mix, who was on the bench for 16 years before retiring in 2023, said she could understand the desire to enforce more concrete expectations of courtroom professionalism.

“Judges get tired of unethical — or borderline unethical — conduct in their courtrooms, especially as the years go by,” she said.

Colorado’s district court sets forth a lengthy list of local rules governing topics as diverse as case assignments, criminal pleas and communications with judges. In addition, each district judge and magistrate judge has practice standards addressing their individual courtroom procedures.

But in the latest round of revisions to the local rules, one unidentified district judge proposed empowering each member of the court to set forth their own rules via practice standards that would be grounds for discipline if violated.

The proposed change to the U.S. District Court’s local rules in red

During the brief window in October for public input, the court received no comments in support and two statements critiquing the proposal in detail.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office, which handles criminal prosecutions and also represents the federal government in civil cases, warned that lawyers would be subject to “a new set of unpredictable rules” established unilaterally by the two dozen district judges and magistrate judges on the court’s bench. Further, it is currently unclear which portions of a judge’s practice standards fall into the category of “professional conduct” subject to discipline.

“After this amendment, all the judges could, without any process, adopt their own individual practice standards or orders setting professional practice standards,” the office argued. “Conduct might be subject to discipline before one judge under that judge’s practice standards even if the same conduct in another courtroom would be permitted.”

The U.S. Attorney’s Office pointed to a related complication: The rule change also lowers the threshold for disciplining lawyers from “clear and convincing evidence” to “a preponderance of the evidence.” Taken together, the new rules could encourage the submission of “marginal complaints” that would be harder to dismiss.

“We recognize that the Court may have good reasons for seeking additional tools to ensure appropriate behavior by attorneys appearing before the Court, and we don’t wish to interfere with that goal. We believe, however, that additional consideration of the best means to achieve this goal is warranted,” the office concluded.

FILE PHOTO: The Alfred A. Arraj U.S. Courthouse in downtown Denver. (Photo courtesy of United States District Court – Colorado)

Damon Davis, an attorney in Mesa County, noted judges can already enforce their expectations by holding people in contempt of court, imposing financial sanctions or ordering attorneys to re-file a motion properly. He called those options a “far more appropriate way” for judges to enforce their expectations compared to a disciplinary process that may result in an attorney’s suspension or disbarment.

“I would welcome a rule change that allows a judge to impose reasonable sanctions in an individual case, while I oppose a rule that allows an attorney’s entire career to be impacted by the idiosyncratic rule of a single judge found in their practice standards,” he wrote in his comments.

Davis raised further concerns not addressed by the rule change: What happens if a case is reassigned? Could the new judge pursue discipline for conduct that occurred prior to the reassignment?

Given the consequences to an attorney’s career, rules of conduct “should be well known, well publicized, and universal so that attorneys can be sure of their obligations,” he added.

At the same time the court updated its local rules, several judges posted amended versions of their individual practice standards. No judge appears to have delineated specific conduct that will be grounds for discipline in their courtrooms.

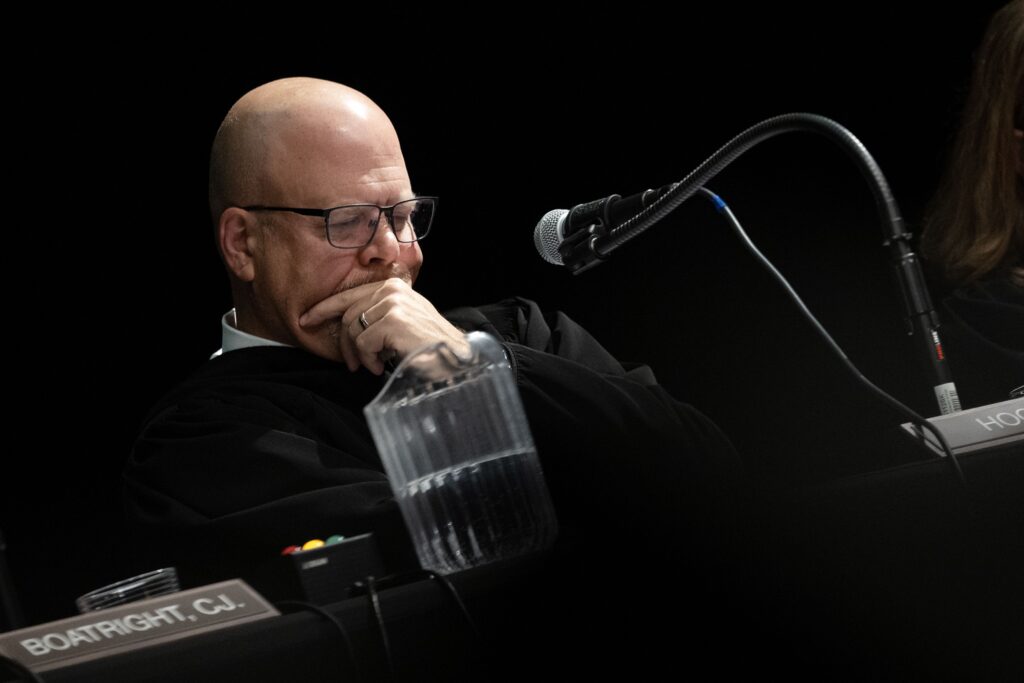

The active and semi-retired senior district judges voted on the court’s rule changes. The amendments also clarify that a defendant being sued by a self-represented plaintiff need not respond to a complaint until a judge screens the filing and determines that it states a claim.