Democrat Robert Marshall revives Republican primary claim alleging ‘dark money’ influence in Colorado House race

Dark-money donors, those who aren't identified to voters, are providing millions of dollars to fund campaign measures statewide and in Colorado's local governments this election season. The practice is legal, but obscures wealthy donors and special interests driving the political discourse from the shadows.

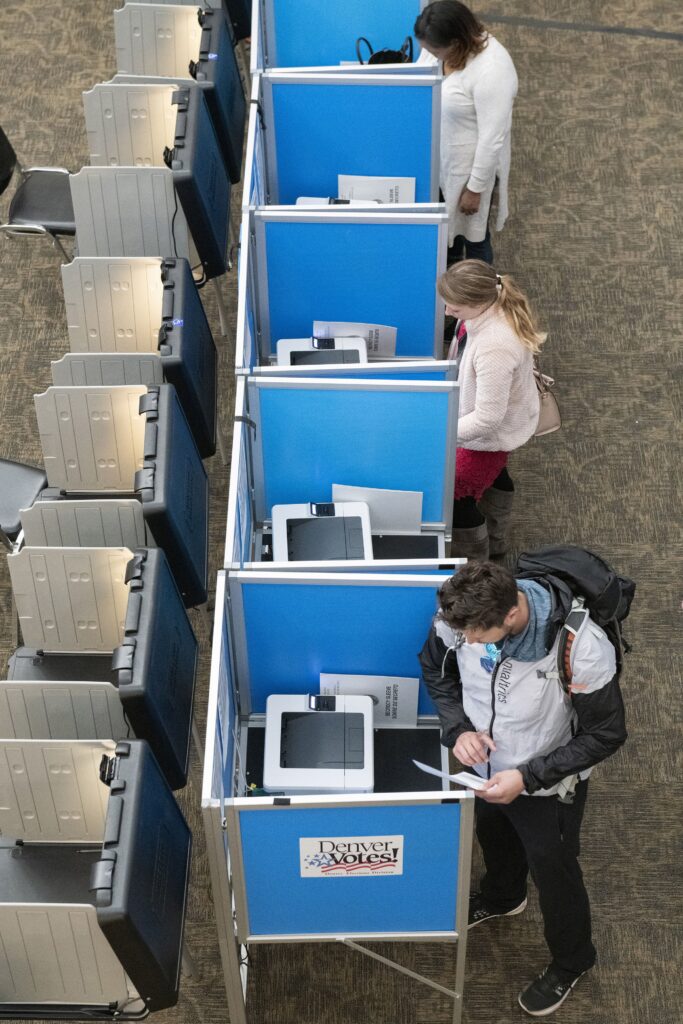

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A Democratic representative gearing up for a highly contested race is reviving a claim that “dark money” played a role in his Republican opponent’s primary victory.

In a post on his X account, Rep. Bob Marshall, D- Highlands Ranch, wrote that “outside dark money is trying to buy the Highlands Ranch state representative seat.” He also claimed campaign finance records from June and July show his opponent, Republican Matt Burcham, did not receive a single contribution from a Highlands Ranch resident, while his campaign secured about 80 local contributions.

“Hundreds of thousands of dollars have and will be spent by special interest dark money in HD43,” Marshall wrote. “DON’T LET THEM BUY YOUR REPRESENTATION!”

Campaign finance records show that Marshall’s campaign has significantly more money than Burcham — $43,219 against just over $5,000.

Independent expenditure groups are prohibited by law to coordinate with candidates. Accusations of the influence of “dark money” in elections — either for or against candidates — are not new. Republicans and Democrats alike routinely benefit from or are the subject of support or attack ads from such groups, which are known as “dark money” entities because they are not legally required to disclosure their contributors.

Marshall posted an image of a campaign mailer stating that $180,000 in “outside money” was spent on attack ads against Douglas County Commissioner Lora Thomas, who ran against Burcham in the Republican primary for the House seat the Democrat occupies.

Burcham, who defeated Thomas by nearly seven percentage points, will face Marshall in November.

Ryan Lynch, a consultant for the Burcham campaign, said Burcham was completely unaware of Keep Colorado Counties Safe and its plans to create attack ads against his opponent.

“It wasn’t anything we were expecting, but it happened, and I can’t pick up a phone and call them,” he said, adding that it’s illegal for him to coordinate with what he calls a “soft-side” group that donates to parties and issue advocacy rather than an individual candidate. Unlike contributions made by political action committees, organizations, or individuals, contributions to independent expenditure groups have no limits.

Like Marshall, Thomas alluded to independent expenditure group Keep Colorado Counties Safe using “dark money” to help her opponent win the primary. The group, which received a total of $300,000 over six contributions signed by Republican political strategist Sean Tonner on behalf of a group called Douglas County Future Fund, has created ads for several Republican candidates around the state, including Elbert County Commission candidate Byron McDaniel and Douglas County Commission candidate Priscilla Rahn.

Tonner was a principal with Renewable Water Resources, a real estate development group that proposed selling water from the San Luis Valley to Douglas County water users. After the proposal failed in 2023, the Douglas County Commission appointed Tonner to the county’s newly-created water commission over Thomas’ objection.

Campaign finance reports indicate that four members of Tonner’s family made donations to Burcham’s campaign, each for the maximum amount of $900. Like other politically active voters, Tonner routinely contributes to candidates.

Unlike “dark money,” the law requires disclosure of individuals’ contributions to candidates.

Marshall claimed independent expenditure groups and people like the Tonners are collaborating to influence the House race.

“They’re supposed to be separate, but there is so much interlocking with campaign money going on that it’s kind of hard to say with a straight face that one hand doesn’t know what the other one’s doing,” he said.

He did not offer any evidence to support his speculation.

Marshall said he’s had to adopt a different approach to campaign financing this election compared to 2022. In the previous election, he estimated that only about 1% of his donations came from outside organizations.

“That’s turning around now because I have to ask for help because there’s no way I can survive a $200,000 onslaught if that comes in the fall, with dark money trying to scare me,” he said. “So, I’ve reached out to several organizations for help. I’m taking money now that normally I wouldn’t from organizations because it’s the only way I can defend myself.”

Marshall said he is confident he will win the general election.

Campaign finance records show that Marshall’s campaign has $43,219, while Burcham’s has just over $5,000.

When Marshall was elected in 2022, it was the first time a Democrat had won a seat in the heavily-Republican HD 43. Marshall also won the seat by a slim margin.

Lynch, the consultant for the Burcham campaign, said he hasn’t seen any outside spending on the general election race between Burcham and Marshall.

“People throw around the term dark money without actually knowing what it is,” he said. “Connecting the dots can generally be very difficult, so I’m not sure that dark money technically applies to this, but again, I’m not in tune to the dynamics of the spending that occurred in the primary. To this point, I haven’t seen a dime in dark dollars or whatever you want to call them spent on the general election.”

Lynch added that Marshall is accusing Burcham of “illegal coordination” without evidence.

“That is reckless, defamatory, and unbecoming of a Colorado attorney and State Representative,” he said. “I understand Bob is desperate, but he needs to do better.”

Noah Feinstein contributed to this story.