Vision Collision: Cherry Creek ponders over super-sized project

Denver’s Cherry Creek neighborhood, with a shopping district that was once known for its quirky charms, has gone through a remarkable run of commercial and residential building projects over the past two decades, with more to come.

And that has residents worried.

A few decades ago, the small area’s boutiques, bistros and galleries were wrapped by shaded neighborhoods, where people could find everything from custom homes to small bungalows that a schoolteacher or gardener might afford.

Now, community leaders are documenting an explosion of offices, hotels and condos that arrived in Cherry Creek just over the past 15 years and neighbors are bracing for an even faster expansion from projects in the pipeline, including a major one — Cherry Creek West, which would add 1.9 million feet of development, including seven buildings as tall as 12 or 13 stories.

The Cherry Creek Alliance, representing the business district from University Boulevard east to Colorado Boulevard, tallied an additional 243,000 square feet of office space that opened in the district over the course of the pandemic through to last year.

With those and other recent buildings figured in, over 54% of Cherry Creek’s offices are now rated as coveted Class A space, according to the group. Along with new restaurants and a tidier street scene, companies wanting their employees back in the office are weighing Cherry Creek’s allure against Denver’s central business district three miles northwest, where offices face numbers of challenges.

Revenues from that presence, along with Cherry Creek’s hotels and retail, generated over $112 million in taxes for the Mile High City in 2023, with some of the windfall coming from 14 million visitors lured by shopping and other attractions.

All of that is leading some developers to ponder whether Cherry Creek is on the brink of becoming an alternative downtown for Denver, and many — worried about preserving what has so far been a golden goose of revenue for the city’s coffers — fear the troubles that may come with that change.

Density on the horizon

“This little area was never intended to be another downtown,” said developer David Steel, who offices in a four-story office at East Second Avenue and Fillmore Street — one of a number of projects his own company created in Cherry Creek over the past decade.

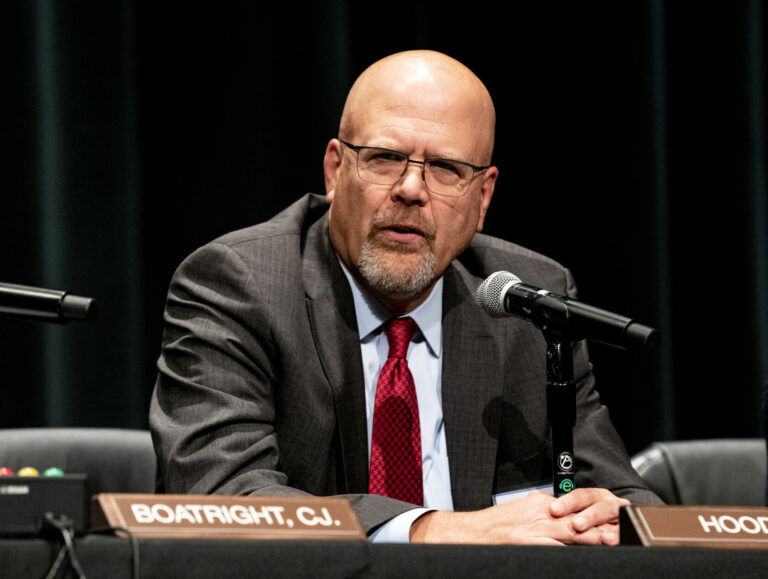

Last month, Steel and former Denver City Councilman Wayne New released a study they’ve titled “Reinvesting in the Future,” probing just how impactful the past 10 years were, and how traffic has been — and might be — affected.

The study starts with projections made in 2013 by a zoning task force that examined the 16-block Cherry Creek North Business Improvement District, north of First Avenue from University east to Steele Street. The earlier study projected that commercial-residential expansion in the area might double over the next decade to 5.3 million square feet.

But Steel’s and New’s assessment puts actual growth over the span at 8.5 million square feet — a 230% increase from 2013’s 2.5 million feet.

And that’s just the beginning of what’s headed into the shopping district, as new projects come online.

A tally by the Cherry Creek North Neighborhood Association puts total office projects either underway or on track for launch north of First Avenue at 800,000 square feet. That’s a figure larger than the footage of a downtown office tower, such as Hines’ recent 40-story tower at 1144 Fifteenth Street just east of Larimer Square, at 670,000 feet.

The arriving office space doesn’t include retail and residential projects set for the tightly packed area, such as Waldorf Astoria condos headed for Second and St. Paul, or BMC Investments’ redevelopment of the Sears site east of Whole Foods — projected for 867,000 feet of new apartments, plus retail.

Meanwhile, south across First Avenue, an even larger project is on the boards for 13 acres west of Cherry Creek Shopping Center, where Bed Bath & Beyond had closed its store in 2017.

That’s where East West Partners — the developer behind LoDo’s Riverfront Park and the Union Station makeover — is deep in the approval process for Cherry Creek West. The proposed seven-building redevelopment would span from E. First, south to the district’s namesake creek and its 40-mile bike trail.

That property, not part of Cherry Creek North, is huge by Cherry Creek’s standards — comparable to four blocks of the older shopping area. New apartments are on tap, some of them to be more affordably priced, along with shopping, restaurants and three additional buildings of offices.

Parking for the three components would be entirely underground.

The project, which has had its preliminary development review framework processed by the city, is still undergoing community review, and East West doesn’t anticipate delivering a building before 2028.

But the sizing looks to add around 1.9 million feet of development to Cherry Creek, with the office component alone set to exceed 600,000 feet.

“If it were a million-nine, that would be double the size of the existing (Cherry Creek) mall,” Steel told The Denver Gazette.

Steel, co-founder of Western Development Group, recalls that he and New came up the idea of the impact study over lunch. A decade before, they had been among advocates who promoted rezoning Cherry Creek North for higher density, which led to a spate of new projects arriving.

Now, Steel readily admitted that his own company’s projects were among those that pumped the area’s growth over the past 15 years.

“We were part of the problem,” Steel said.

Those successes started with NorthCreek luxury condominiums at 100 Detroit — a project, he said, that came out of the ground in 2008, as the nation was headed into the Great Recession.

Sales struggled for two years, but the project sold out, helping prompt a wave of surrounding development that ran counter to the national downturn.

Today, Steel and New worry that planners are missing the impact that large scale projects, including Cherry Creek West and the Sears redevelopment, would have when they open.

“Nobody is looking at that now. In my opinion, it’s out of scale for the neighborhood,” Steel added. “It will generate an inordinate amount of traffic.”

Cherry Creek West

Amy Cara, managing partner at East West, claimed that concerns being raised about Cherry Creek West are outsized to realities and that the size and density the project will be offset by the significant benefits.

“Connecting the neighborhood to the creek through this site is the key vision,” Cara told The Denver Gazette, during a walk across the parking lot of the old Bed Bath & Beyond store, south to where the creek and trail run by.

East West’s vision includes a 20,000-foot parklike “green” that would open north into the site from Cherry Creek North Drive, along with bike-pedestrian corridors spanning the project end to end. Some 40% of the site would remain as outdoor or non-building areas, including grassy zones that could host Colorado Fresh Markets and other events that have been staged on parking lots.

“Cherry Creek doesn’t really have a lot of open space, not one that can be everyone’s front yard,” Cara said.

East West’s plan, she said, leaves more space undeveloped than the city had asked for. That includes the interface with the creek and trail. East West’s plan initially called for a land bridge across Cherry Creek North Drive to serve as a green connection to the pathway. But city planners, said Cara, didn’t like the long underpass that would be required beneath the bridge.

Revised plans call for two crossing points on the drive at grade level, each with stop signs and raised platforms to calm traffic. One bike crossing around 18-feet wide would line up with Clayton Street at the east end of the site, and another scaled at 20-to-25 feet wide would center on the community’s “green.”

The plan also provides major improvements to widen the trail to better accommodate a mix of bikes and pedestrians, according to Cara.

How about the individual buildings themselves and their impact on the site?

Cara said that the seven building shapes on current site maps are just placeholders for now but insisted that the density will look good compared to the older shopping area to the north.

“Look at how close all these buildings are in Cherry Creek North,” Cara said. “Here there is more space, it’s very porous.”

Along with the Bed Bath building, one landmark west of the mall that would disappear is Elway’s Steakhouse, a popular attraction since 1994. But Cara said there is hope it will transit into the new mixed-use area.

“We’ve been talking with them since the beginning, even before we went public,” Cara said. “They’ve said they’d really like to stay.”

Bad traffic about to get worse?

Steel and New’s study suggests that an additional 1,922 vehicle trips would be generated by the project, boosting traffic at First and University, which is already reaching its maximum capacity during rush hours. The city’s Denver Moves: Cherry Creek study released last month pinpoints the intersection as already handling a high volume of traffic and posts a high level of delays during some dayparts.

Also implicit in the study is the assumption that any projection will likely underestimate actual growth, just as the 2013 estimate understated the development that materialized over the last 10 years.

Asked about the traffic concerns in Steel’s and New’s report, Cara noted that she has had close associations with Steel through the Cherry Creek Business Alliance and met with both authors during the report’s preparation.

“Lots of facts about our site (in the report) are wrong,” Cara claimed.

East West, she said, is at work on its own traffic study, using a city derived methodology to examine the impacts. “The East West study shows substantially less traffic, almost half of what they’re projecting,” she said.

Cara also suggested that the report’s algorithms, which pegged the number of expected car trips to office square footage, are out of scale.

“What that does, or seems to show, is that our traffic impact is substantial when it’s really not.”

Nick LeMasters, president and CEO of the Cherry Creek Alliance, also said that traffic worries at the site are overblown.

“We already know we have an intersection at First Avenue and University that is challenged, but that really occurs only in two dayparts, from 7 to 9 a.m. and from 4 to 6 p.m.,” LeMasters said. “If you’re driving down First any other time of the day it’s not a significant problem.”

Both proponents and critics of the project note that much of the traffic through the area via E. First Avenue is through-traffic headed through the corridor to downtown — a kind of “I-25 lite” that isn’t generated by Cherry Creek.

But David Steel stands by his study’s perceived impacts of the new projects.

“You can get traffic studies to show whatever you want,” Steel told The Denver Gazette. He noted that, although some available data is four years old, he and New returned to original sources for confirmations and are confident that, even if their projections are off by 10%, they aren’t missing the impact by larger margins.

“The (actual) volume isn’t going to be a half or a third off,” Steel said.

Regardless of whether or not the new projects generate more ongoing traffic, won’t the effects from construction traffic be sizable?

“Absolutely correct,” said Steel. “Construction traffic will be awful.”

Area residents express concern

Neighbors to the project share that fear over traffic woes, as well as from the density of apartment construction envisioned in the two projects.

West across University, the board of historic Country Club neighborhood passed a motion in June calling out the size of the East West and BMC projects. The board offered support only if buildings in Cherry Creek West are kept to eight stories as allowed in parts of Cherry Creek North.

“At least the (Cherry Creek North) BID has multiple access and exit paths, where CCW (Cherry Creek West) traffic flow will be a disaster,” the board statement concluded.

“CCW presents the same concerns we’ve had before,” said Jesse Morreale, acting president of the Seventh Avenue Neighbors Association, northwest of Cherry Creek. “We’re right between a lot of the development and are witnessing the failure to plan for the infrastructure necessary around us.”

Morreale questioned whether schools would be able to support the increased density, and whether all of the projects would heighten existing problems of construction workers who park on crowded neighborhood streets.

“It’s no secret that Colorado, University, Josephine and York (streets) are challenged traffic corridors. Just drive it,” Morreale said. “How is that clogging to be accommodated?”

Realtor Coleen Sanders with LIV Sotheby’s — whose book of business is in Polo Club and other luxury areas near the shopping center — said the projects have the attention of a few potential sellers, weighing whether the possibility of added congestion would make this a good time to sell.

A key aspect, she said, is access to grocery shopping, with the closest at Whole Foods, north of the projects’ major intersection.

“Most people are excited by it,” she added, noting she doubts the projects will negatively affect property values.

“I appreciate what they’re doing, but I’m not looking forward to increased traffic,” said Talia Ballinger, a resident along the Seventh Avenue Historic District, who commutes daily to a gym located in a temporary site within the targeted property, beside Elway’s.

“I think now it’s fine, but if one lane gets closed off, the whole thing explodes.”

Cara, LeMasters and others close to the process say that the City and County of Denver is largely supportive of adding density — both to bring more housing and to create work-live-play environments that use less transportation.

At Cherry Creek West, the residential side will be entirely apartments — no condos allowed. That’s a requirement set by the Buell Foundation, which would lease the 13-acre site to East West. Denver developer Temple Buell acquired the original property in 1925 and built the original shopping center in 1949.

According to Cara, building heights will top-out at 12 or 13 stories and average 10.5 stories. She noted that a recommendation in New’s and Steel’s study for changing the composition from four offices and three apartment buildings to three offices, four apartments, has already been made in East West’s newest vision.

However, Steel and New’s study also request that the project be limited to eight stories as a means to help control traffic. The study says office buildings and retail businesses attract markedly more traffic than residences, and that eight-story buildings would be consistent with current zoning at the business improvement district.

“We are not doing that,” Cara said. “The city doesn’t want us to do that.”

The heights are less than the 2012 Cherry Creek Area Plan had projected, she said. “Going to eight stories isn’t going to impact traffic much,” Cara said.

Supporters of the project maintain that plans are consistent with broader city plans for growth in the near term, including a Denver Moves plan for Cherry Creek that was released last month.

A drain on downtown Denver?

Meanwhile, how substantial are worries that Cherry Creek’s momentum has become a drain on Denver’s central business district, struggling with high office vacancies, ongoing 16th Street Mall construction, and other optics problems?

“It’s a very compelling question,” said urban planning authority Andy Cushen, who follows development for the blog site DenverInfill.com. “I think that downtown is going to feel different.”

The Alliance’s LeMasters, who calls the flow into Cherry Creek a “flight to quality,” said that demand for offices in Cherry Creek shows no sign of abetting.

“Most projects under development are completely pre-leased before they go under construction,” he said, adding that project lenders love to see that.

“We need our downtown CBD to come back strong,” LeMasters added. “Cherry Creek drafts off downtown. We’re a vibrant submarket, but we’re supportive of efforts to revive downtown, to get people back in the office.”

Cara, noting that East West began exploring the Cherry Creek West project with the Buell Foundation back in 2003, said that the developer is committed to success in both areas.

“We intend to own this for long time,” she said.

Cara’s own office is part of the Union Station redevelopment in LoDo, where she said she is already seeing more street life, as the town works to reduce the post-pandemic homeless issue.

“There are some buildings that are really challenged, but new buildings will do well,” Cara said, adding that she’s exploring a residential project for a downtown property yet to be purchased.

“I see future for Cherry Creek to really thrive without being a negative for downtown.”

But report co-author David Steel said that downtown’s problems only add to his fears about the direction of Cherry Creek.

“Traffic is what will choke everybody. We’ve seen that from day one,” he said. “When they can’t find a spot to park in front of the store where they’re going, they won’t stick around.”

“The other day my wife and I went to LoDo, and you stand there, it’s like another little downtown,” Steel added. “That’s what it’s going to start looking like in Cherry Creek.”

Seventh Avenue resident Talia Ballinger waxed nostalgic. “It used to be so bohemian,” she recalled of the shopping district.

“I hope they can salvage some of the quirkiness.”