Bill requiring voting service centers in jails divide Colorado county clerks

A panel of state senators is expected in the coming weeks to take its first look at a bill that has divided the usually united county clerks in Colorado over allowing people in jail to vote on election day.

The proposal could cost the state between $200,000 and $1 million.

If passed, Senate Bill 72, which was assigned to the State, Veterans and Military Affairs Committee, would require county clerks to set up voting service centers in jails and detention facilities to allow eligible prisoners to vote.

Clerks in the state’s smaller counties are calling it an unfunded mandate, while sheriffs are taking issues with the bill’s language regarding possible penalties for jail facilities not in compliance. Supporters, meanwhile, say it’s about access to a fundamental right.

The bill’s fiscal note shows a state cost of $200,000, but opponents claim the real cost could be closer to $1 million, largely due to the cost of equipment that will be needed in every county jail. That could become an unfunded mandate for county clerks who will have to cover those costs from existing budgets, critics say.

Clerks who support the measure, including those in Arapahoe, Denver, and Jefferson counties, point out that people in jails are often incarcerated pre-trial — meaning they have not been convicted of a crime or are serving sentences in a county jail for misdemeanors, which makes them eligible to vote.

Jefferson County Clerk and Recorder Amanda Gonzalez told Colorado Politics there are a variety of ways to set up special voting centers, which would not be available to the general public for obvious reasons. Elections staff could set up a ballot-marking device in a jail or detention center and print ballots on demand, she said. An in-person voting site could require three to six election judges, who are temporary employees, plus some full-time staff, she added.

Gonzalez estimated the cost for her county at between $1,400 and $3,500, depending on the kind of equipment needed. She said there are about 1,000 people in the Jeffco jail on any given day and 60% are there for pre-trial.

“We see voting as a fundamental right, and all eligible voters deserve to have a voice in that,” she said.

Gonzalez called voting “an action we take to express a better hope for tomorrow, and these are the people we want a better tomorrow for. It’s balancing a fundamental civil right.”

Small counties express worry about staffing, funding

The bill worries county clerks in El Paso, Douglas, and Weld counties, along with others who represent small to medium-sized districts in the state.

Matt Crane, executive director of the Colorado Clerks Association, raised several points against the proposed measure, beginning with staffing and funding.

He described Denver as a “unicorn,” a county able to deploy resources and staff into jail and detention center voting centers.

That’s not the case for the other 63 counties, Crane said.

“It’s a resource issue, and (the county clerks) are stretched pretty thin as it is,” he said.

Crane raised the scenario of what happens when a sheriff, who oversees the voting centers at the jail, is on the ballot and whether that might create undue influence.

Meanwhile, El Paso County Clerk and Recorder Steve Schlieker noted the potential for damage to voting equipment from inmates with mental health issues or who may just be inclined to damage property.

Discussions are ongoing around amendments that could address some of those concerns, such as mandating voting centers in larger counties where they have the resources and looking for more drop-off ballot boxes for the smaller counties.

Current state law requires clerks to work with the sheriffs to ensure inmates have a chance to register to vote and that jails can collect and deliver ballots. Gonzales explained that doesn’t have to be on Election Day — that it could be within a few days of the November election. That would keep small county clerks’ offices and staff available on Election Day, she said.

SB 72 requires county jails and detention centers to offer at least one in-person voting day of up to six hours for eligible confined voters for each general election. The sheriff’s designees must provide voting information to voters confined in those facilities and coordinate with the local county clerk to set up a mail ballot and ballot curing system within the jail.

Kyle Giddings, the civic engagement coordinator for the Colorado Criminal Justice Coalition, said ballot access is “incredibly difficult” around jails, he told Colorado Politics.

Currently, voting doesn’t draw much participation from those incarcerated in the county jails. He said in Douglas County, only one person has voted out of 263 people on pre-trial detention. Similar numbers were seen in Jefferson Boulder, El Paso, and Adams counties, where only a handful of people requested ballots out of hundreds incarcerated, Giddings said.

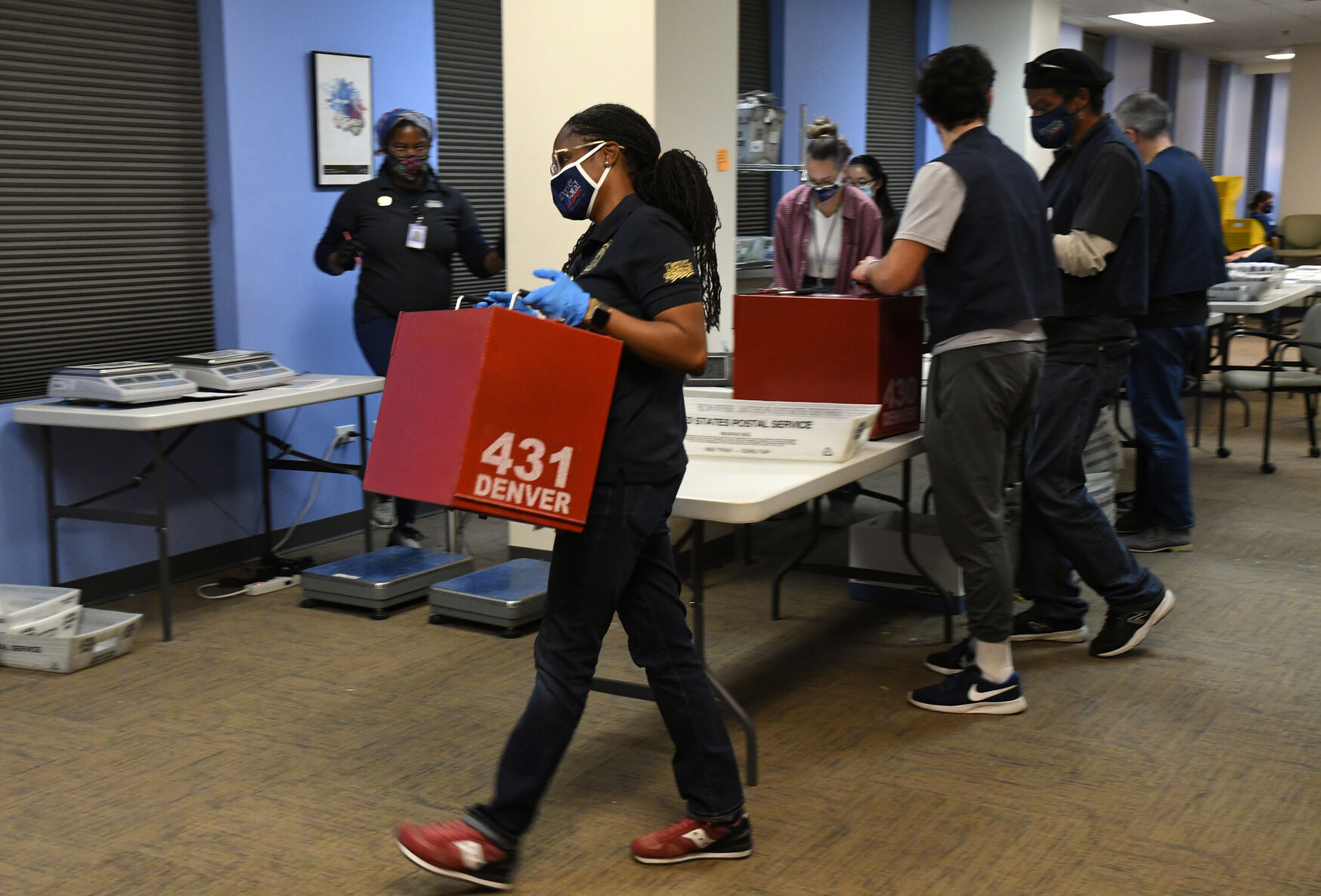

Giddings said his organization has been going to jails for voter registration since 2016 and helped launch in-person voting in Denver in 2020. In the most recent June runoff election for mayor, they had 58.7% turnout at the jails, compared to 36% for the general public, he said.

Giddings acknowledged the concerns from the sheriffs that having voting machines in jails will create logistical headaches, requiring background checks and security barriers. But he pointed out that civilian volunteers go into jails all the time for re-entry work and religious purposes without problems.

“The same policies and safety concerns one would have for a religious organization should apply here,” he said.

On the issues of staffing and costs for small and medium-sized counties, Giddings noted that in 2018, the Colorado Secretary of State put in a rule that county clerks had to facilitate voting in jails, but it’s not happening.

“Clerks have had the mandate to facilitate voting in the jails. It’s time to change the process,” he said. “Rural voices matter.”

County official: Not a ‘responsible use’ of taxpayer dollars

Schlieker said election judges personally deliver ballots to voters who are incarcerated, and they can vote and cast their ballot in a secure ballot box conveniently located at the facility.

He pointed out that voting by inmates has traditionally drawn little interest.

In the last two years, only one person voted, he said.

Crane of the Colorado Clerks Association also pointed out that the bill, as introduced, does not include some of the same procedures that exist for elections at all other voting centers, such as allowing for watchers from the political parties who traditionally are on hand at the voting service centers.

That’s listed as a “safety issue,” but opponents of the bill claim the safety issue should also apply to the election judges and county clerk employees who will run those voting centers.

Clerks push for more transparency, not less, Crane said.

“We can’t expand a voting process that doesn’t include meaningful observation” nor create carveouts for any one facility. “We’re already dealing with mis- and dis-information on elections,” he said, adding it’s not a good idea to create new avenues to vote without meaningful citizen oversight.

On that issue, Gonzalea responded that there’s an “important distinction that in-person voting options at a jail are not exactly like a voting center.”

It’s more akin to what clerks have been doing at health care facilities, for example, which is to bring in nonpartisan staff to handle elections, she said, adding that was common during the pandemic.

Gonzalez also insisted the low turnout numbers — three in 2022 and six in 2023 — are not a reflection of a lack of interest. She said she believes the low numbers indicate a system that isn’t working.

“We have to meet people where they’re at,” she said.

The current system, which requires someone to ask for a voter registration form from a deputy, then wait for the ballot and fill it out in front of a deputy, might not encourage people to vote, she said.

Gonzales said she is committed to transparency and hopes to hear creative solutions, noting she is not opposed to having watchers.

“We would have to work with the sheriffs to see what that would look like and make sure eligible voters have meaningful access to the ballot,” she said.

Schlieker zeroed in on the measure’s potential cost.

The voting centers would not only need voting machines, but they would also need security cameras, all of which come at a high cost, he said.

“It is not a responsible use of taxpayer money,” he said.

Editor’s note: corrected spelling of Gonzalez’ name and the number of individuals who voted in 2022 and 2023.